Every era has its witches. At least, that’s how it seems from the British Museum’s current exhibition Witches and Wicked Bodies, which is showing in Room 90 until January 11th 2015 (entrance free). Here, ancient sorceresses like Medea and Circe mingle with Eve, Lilith and the Witch of Endor, while the nameless crones of the Early Modern witch-hunts cackle alongside the Weird Sisters of Macbeth.

I’d been drawn to the exhibition by the promise of ‘several classical Greek vessels’, and was curious to see which of the museum’s pieces would be used as examples of ancient witchcraft (always a slightly problematic category when thinking about Greco-Roman religion). The pots on display turned out to include the famous vase showing Odysseus sailing past the Sirens, and another depicting the mythical princess Medea rejuvenating a ram in a cauldron.

These classical women reappeared throughout the exhibition in works by later artists, who often mixed occult imagery from a variety of historical periods. One Renaissance Circe stirs her wand in a pool full of strange creatures, while her eighteenth-century neighbour uses a spell-book and magic circle.

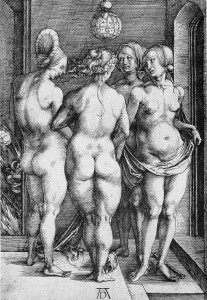

Perhaps the strangest concoction of classical and later imagery was Albrecht Dürer’s engraving The Four Witches (1497), which at first sight looked exactly like familiar ancient scenes of the Three Graces. Dürer transforms this iconic symbol of classical beauty into an uncanny spectacle of mischief and decay, adding in a fourth cavorting figure, a grinning demon, and a discarded human skull. On the sphere hanging from the ceiling we see the initials O.G.H., which some scholars think represents ‘God Save Us’ (O Gott hüte) – a quiet, desperate appeal to a reassuringly disembodied deity.

I went to this exhibition in search of classical imagery, and got slightly more than I’d bargained for. Throughout the period of the European witch trials, artists seem to have been experimenting with the great femmes fatales of classical myth, and using them as a way to think about the relationship between women, bodies and the supernatural. The witches who were hunted and put on trial were often imagined as modern-day Circes and Medeas, and the weight of these esoteric classical references must have made them seem all the more threatening. God save us? Perhaps that’s what they thought.

Witches and Wicked Bodies is on at The British Museum until 11th January 2015.

Dr Jessica Hughes (Classical Studies, Open University)