By John Maiden.

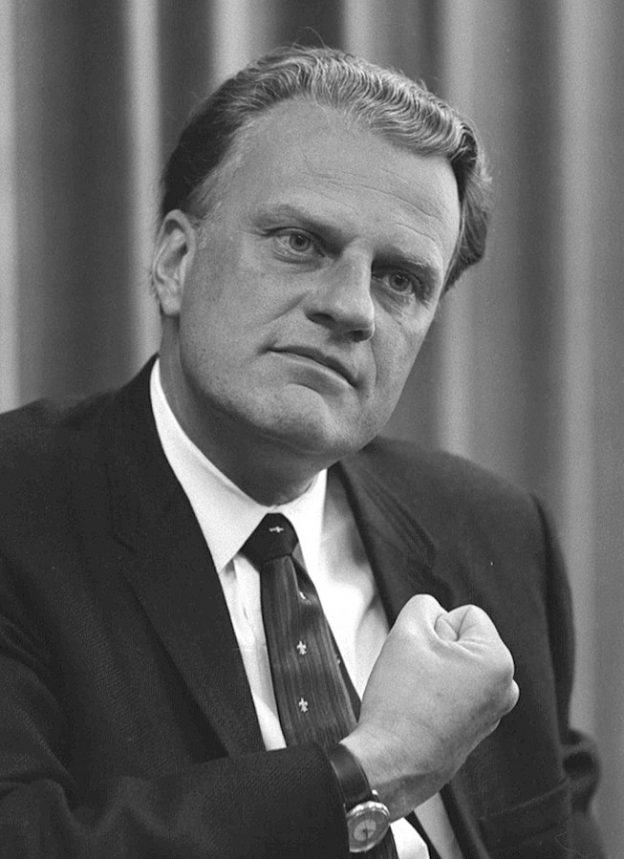

Billy Graham died today. While he had been out of the public eye for some time, his passing will prompt many historians of religion to assess a remarkable – and remarkably long – religious career. These are brief, general reflections, written quickly, and which will no doubt require further thought. They only scratch the surface of his ministry and impact.

Graham experienced an evangelical conversion in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 1934. In the 1940s he felt he was increasingly drawn towards evangelism, and over time developed a nation-wide reputation. His landmark Los Angeles ‘crusade’ in 1949 saw around 350,000 attend meetings over two months. From 1946, through his role with Youth for Christ, an international ministry also emerged. In 1954 he was invited to lead the Greater London Crusade. While the idea of a resurgence in British religiosity in the 1950s is contested amongst historians, his visits, followed the next year by evangelistic missions in London and Glasgow, were defining moments in post-war British Christianity. These visits also opened access to Britain’s Commonwealth networks: he toured India from 1956, Australia and New Zealand from 1959, and various African nations from 1960. As Britain’s global influence declined, and America’s political, economic and cultural power expanded further, Graham became the key figure in American Christian internationalism. In an age of Cold War anxiety, his evangelistic message was widely seen as a Western spiritual bulwark to communism. Later, in 1974, Graham had a leading role in the organisation of the Congress on World Evangelization in Lausanne, Switzerland. As various scholars have noted, this was to have an important impact, as majority world evangelicals began to exercise influence on the west, challenging narrower notions of Christian mission.

Graham’s evangelistic career brought together revivalism, ecumenism, technology and celebrity. The extensive local preparation for his missions encouraged a dynamic of ecumenical cooperation, and later his inclusion of Roman Catholics drew criticism from some evangelicals. He innovated in the use of media. From 1951 he pioneered the use of evangelistic movies (and I very clearly remember being taken to one in the late 1980s), and in 1954 his preaching in London was transmitted to churches and theatres around the country. Graham himself was a widely recognisable religious celebrity, and many secular celebrities were drawn to Graham.

Since the eighteenth century evangelicalism has been highly diverse, sharing, as David Bebbington has argued, four general characteristics of crucicentricism, conversionism, Biblicism and activism. However, in the United States, Graham made an important contribution to the emergence of something like a post-war American ‘new’ evangelical movement. The death of Graham – sometime after his retirement from public ministry – will invite further reflection amongst scholars of American evangelicalism about the present-day coherence of this movement. To what extent is it now a constellation of different constituencies, each with different priorities and agendas? Furthermore, with the death also of the Revd. John Stott, the English Anglican who also enjoyed an international leadership role, perhaps a similar kind of question about evangelicalism will be asked on a global scale. No single evangelical figure now has the same worldwide reputation. If such an individual is to emerge, perhaps they will come from the majority world?