Visitation Returns

What are they?

Visitation returns are amongst the most valuable sources for finding out about churches and parishes. Visitation returns make up an important part of the Fulham Papers. Visitations were conducted either by the archdeacon or bishop, and were originally administrative occasions at which churchwardens were sworn in and asked to report on the morality of the clergy and their parishioners. By the eighteenth century, visitations had evolved, with enquiries now directed to local ministers and curates as well as churchwardens. By the nineteenth century they asked for comment on a range of questions about the church and its parish. Intermittently they allow us hear the voice of clergy commenting on the condition of their parish (or churchwardens commenting on the condition of the cleric!).

Where can I find them?

Bishop’s visitation returns, which by the nineteenth century were generally completed by ministers and curates, are found in the Fulham Papers held at Lambeth Palace Library. The only exceptions to this are Winnington-Ingram’s visitation returns for 1905 and 1911, which were instead deposited at Guildhall Library entitled ‘Completed articles of enquiry, 1905’ and ‘Completed articles of enquiry, 1911’ (Ms 17885 and Ms 17886). No returns exist for Hayter or Fisher. Hayter’s sudden death in 1762 meant that no visitation was conducted in his name. The Second World War might have prevented Fisher from conducting his primary visitation. However, visitations were also discontinued in the period.

Churchwarden visitation returns, which by the nineteenth century were generally responses to visitations made by archdeacons, are held by Guildhall Library under the title ‘Churchwardens’ presentments, 1610-1911. Summaries can be found for the Archdeaconry of Middlesex in two tables at the front of Blomfield volume 70 in the Fulham Papers held at Lambeth Palace Library.

For more information on visitation returns, see Melanie Barber’s An Index to the London Diocesan Returns in Lambeth Palace Library, 1763-1900 (1991) available at Lambeth Palace Library.

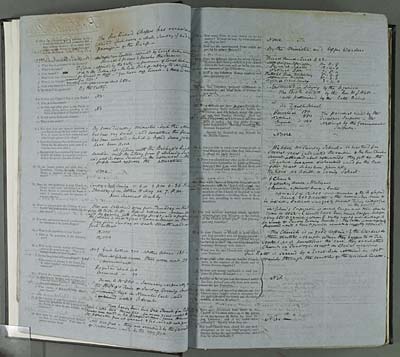

Visitation returns can give useful insights into the life of church and congregation. This shows a page of the returns for St Matthew, Bethnal Green, for Bishop Tait in 1858. (Image courtesy of the Trustees of Lambeth Palace Library).

Descriptions of material

Bishop’s Visitation Returns

Visitation returns make up an important part of the Fulham Papers. Visitations were conducted either by the archdeacon or bishop, and were originally administrative occasions at which churchwardens were sworn in and asked to report on the morality of the clergy and their parishioners. By the eighteenth century, visitations had evolved, with enquiries now directed to local ministers and curates as well as churchwardens. Local ministers filled in the queries and returned them to the bishop, either before or during the visitation. They are a valuable source for finding out about bishop’s concerns and the state of the parishes and the clergy’s attitudes to their condition.

London visitations were generally conducted every three to four years, but only the returns for 1763, 1766, 1770, 1778, 1790, 1810, 1815, 1842, 1862, 1883, 1891, 1895 and 1900 have survived in the Fulham Papers. Visitation queries and returns often covered similar grounds, but usually in increasing depth as time proceeded. Returns were usually written up on printed questionnaires. Eighteenth-century questionnaires enquired about the parish, curate, parsonage house, schools and hospitals, and Christians outside the Established Church such as Catholics, Methodists and dissenters. By Randolph’s visitation of 1810, questions extended to youth and behaviour in the parish. Blomfield extended questions to the number of people attending Sunday service, how Sunday was observed by both the clergy and parish and the material fabric of the church buildings. This was expanded further by Tait, whose 37 visitation queries (or articles) became the model for future enquiries. His questions explored the same themes as earlier bishops’. In some cases, the visitation enquires allowed the individual bishops to ask questions of particular interest to them. Blomfield, for instance, encouraged his ministers to comment about education.

The original visitation returns for 1891 and 1895 have not survived. They have instead been summarised in table form in the Temple papers, volume 44. Information noted in the table shows the average number of communicants at Easter and other times, the number of services and sermons per week, congregation size on Sunday morning and evening and on week-days, hindrance to clergy in the form of drink and public houses, parishes’ immorality, insufficient staff, lack of support from the ‘Educated Classes’ and other causes and the total number of baptisms in a year.

Churchwarden Visitation Returns

Archdeacon’s visitation articles were directed at the churchwardens ‘with a view to assist you in framing you Presentments, a duty you are bound, by your oath of office, to discharge faithfully, and with a strict regard to truth’. These enquiries were principally concerned with the condition of the Church and church year, the interior of the Church and the administration of Divine Service. They also enquired about the size of the parish, the populace, the number of families, tithes, poor rate, schools (local or Church of England) and the nature of dissenting religion in the parish.