by SarahJane Mukherjee

Concerns remain high about the impact of the pandemic on children’s education, and initiatives to assist children in ‘catch up’ remain under the spotlight. However, as we emerge from this latest period of lockdown, PlayFirstUK, a group of academics from different universities, has written to the education secretary, Gavin Williamson to suggest that focus be placed on children’s mental health, and instead of ‘catch up’ children be allowed to play with friends and be outside in a ‘Summer of Play’. In anticipation of a potential perceived play/learning dichotomy, they write, “This is not an either-or decision. Social connection and play offer myriad learning opportunities and are positively associated with children’s academic attainment and literacy.” Implicitly, PlayFirstUK highlights that literacy is not confined to learning phonics and building sentences. Yet, one challenge is that while it is accepted that children learn through play, it is not always immediately obvious how or what they learn in relation to literacy.

Here I outline how role-play offers opportunities for literacy learning. The research I draw on, taken from my own PhD study, on was conducted in a classroom with small groups of 4-5 year old children, yet the beauty of role-play is that it is unconstrained by location and takes place in gardens, kitchens, dens, cardboard boxes and under tables. Furthermore, expensive and purposely designed props are not required. The heart of role-play is the social connection and language interaction between the children. Typified by dialogue performed as a character, i.e. where the children ‘are’ the doctor, patient, shopkeeper, there is also language organising the role-play (who takes which role, direction of the action, comments on props). Also present is language sparked by the play but not directly related. Characteristically the children move seamlessly between these functions and the interwoven threads together provide a rich and dynamic linguistic context through which children develop literacy. So, what is it that role-play offers in terms of literacy?

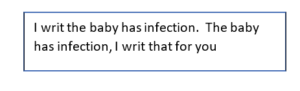

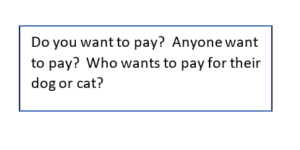

With the availability of pencils and paper, children will write a shopping list or capture details of a patient at a doctors’ surgery. Emergent literacy is well-established in the literature, and in addition, these moments of literacy are accompanied by the children talking about the writing. Thus, role-play becomes a meaningful context for children to write and talk about writing.

While not as visible as writing nor the immediate focus of early literacy programmes, the development of semantic fields, cause and effect and decontextualised/ abstract language are important for a child’s developing literacy and ‘academic’ language more broadly, and these aspects are found by paying close attention to the language interaction.

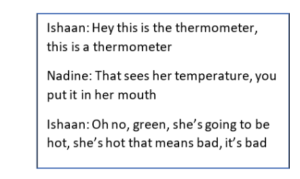

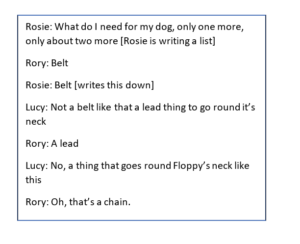

Semantic fields are foundational in a child’s development of their vocabulary. Through the linguistic context of role-play, a child has the opportunity to do more than memorise a new sequence of sounds, but learn how new words are embedded within semantic fields and how they fit within particular grammatical structures and collocations. Learning the word thermometer in the context of a doctor’s surgery, a child develops their understanding of the semantic field around medical equipment and the opportunity to be able to use the word for themselves in this context.

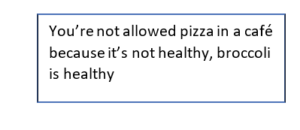

Secondly, the ability to express and understand cause-effect relations in language is of huge importance for the expression of academic meaning. In role-play children have opportunities to negotiate meanings and relationships between ideas and justify their position to their peers. Children use and practise the language of cause and effect to justify their adherence to their own guidelines for the play or justifying particular roles.

Thirdly, props (whether realistic or not) appear to act as a bridge between the here and now, towards the expression of abstract concepts, important for later literacy. Opportunities open for the children to shift their understanding from the contextualised nature of the item e.g. a thermometer, towards a more abstract explanation of the implications for a high temperature.

While potentially reassuring to understand that ‘literacy’ may be happening in role-play, more reassuring would be to understand how these moments of learning are created.

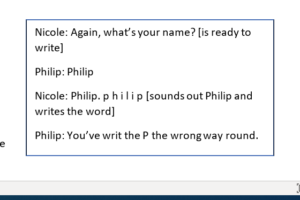

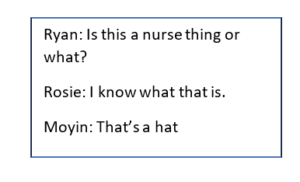

Opportunities for learning are created by the children’s dialogic interaction through repetition. Sometimes subtle lexicogrammatical shifts within the same turn are seen where the children practise, thereby experimenting with their developing language.

In a group the children position themselves as experts and treat each other as such. Their expertise is seen through the children both offering new information to the group and responding to their peers’ questions as they explore the props and position themselves as an ‘expert’ doctor, shopkeeper or restaurant owner.

Thirdly and notably, children create long language exchanges. Often prompted by a question, the children co-construct knowledge over a series of turns. Looked at this way, exchanges where the children do not quite achieve a ‘correct’ answer are also of value.

In summary, even if language in role-play does not quite yet adhere to conventional grammatical rules, or if there appears to be a disagreement about a prop or action, or children’s responses to questions are incorrect, the children learn important literacy skills from and in collaboration with each other as they learn language, through language and about language in the most social of all play, role-play.