PhD student Samuel Aylett has written a piece for the Mainly Museums websites on the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam.

The Tropenmuseum began life as the Koloniaal Museum (Colonial Museum) in Haarlem founded in 1864. Like many nineteenth-century European museums, its collections grew out of Dutch colonial expansion and scientific research. The majority of its collections were brought back from the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia. In 1910, the Vereniging Koloniaal Institut was founded, which was incorporated into the museums in Haarlem, and began to exhibit much of the museum’s collections to the Dutch people. However, it was not until 1926, when the collections were re-housed in the new Colonial Institute and Museum in Amsterdam, that the Colonial Museum proper opened its doors to visitors. It was officially opened on 9 October 1926 by Queen Wilhelmina. Like many European museums, it was closed during the Second World War. In 1945 the Museum changed its name to the Indisch Museum (Indian Museum), and subsequently the Tropenmuseum (Tropical Museum), not least because of the political implications of decolonisation. In the 1970s the Museum was extensively renovated. An extension as wadded to house the Tropenmuseum Junior (children’s museum), a theatre and additional exhibition space (other structural changes were made).

The Tropenmuseum, even today, is a stark reminder, with its impressive neo-classical architecture, of the Dutch colonial enterprise. Like its other European counterparts, the Tropenmuseum would have served to remind and inculcate within the Dutch people a sense of the grandeur and moral obligation of the Dutch ‘civilising mission’. Like the Natural History Museum in London, its façade is decorated with colonial imagery, and images of formerly colonised peoples working in the rubber industry can be seen inside. However, today, the Tropenmuseum is one of but a few museums in Europe that engages seriously in challenging and questioning its colonial past and institutional legacies.

In 2003, the museum staged a new exhibition ‘Oostwarts’, which historian Professor Robert Aldrich felt was the ‘most thorough and thoughtful display on colonialism’. The exhibition, which has now been integrated into the Museum’s permanent galleries, combined both material items and mannequins to interrogate thoughtfully the lives and experiences of peoples living in the Dutch East-Indies. This exhibition marked a post-colonial shift at the Museum, and the beginning of a new period of serious self-reflection about the Dutch colonial past and the Museums own institutional complicity in it.

The Museum’s own colonial legacies are made explicit throughout the Museum’s permanent galleries. During my visit in December, I was struck by a text panel that called into question how the Museum came into possession of its collections from New Guinea.

Where contemporary debates around former colonial museums and acquisitions of their collections tend to be polarised, the Tropenmuseum is nuanced; injecting honesty and self-reflection into an otherwise febrile debate. Other text panels scattered throughout the permanent galleries provide, for example, explanations of Dutch and European colonialism; ‘Colonialism refers to the practice whereby one country conquers and occupies another using force, deception and betrayal.’ Perhaps a little provocative and emotive, but which represents a willingness to take stock of the darker elements of Dutch colonialism.

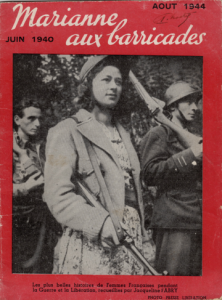

The cardinal reason for my visit in December last year was to see their new permanent exhibition, Afterlives of Slavery. The exhibition focuses on the enslaved and their descendant, using personal stories both past and present to interrogate the history of slavery and its current-day legacies. Personal accounts and memory have become hallmarks of the post-colonial exhibition. The exhibition was designed and created by curators, artists and activities, providing a more democratic and multi-vectored interpretation. Often, public discourse around European colonialism fails to recognize the historical continuity of its legacies and their effect on contemporary society. It was therefore refreshing to see that the exhibition tackled subjects such as ‘Power and Race’, and ‘Protest Against Racism’, explaining the ways in which European colonialism played a significant role in creating racial power structures based on white supremacy which continue to disadvantage and oppress minority groups today.

The Tropenmuseum is a refreshing example of how a country can, with pride, tackle its difficult past at a time when other European Museums are entrenchment in their refusal to engage seriously with their institutional legacies. The Museum is unashamedly self-critical in its reassessment of Dutch colonialism. At a time when the British Museum refuses to entertain repatriation of artefacts taken from former colonies, the Tropenmuseum stands-out in their sincere approach.

Visit

19 years and older: € 16,00

4 – 18 years * and students: € 8,00

Children up to 3 years: Free

CJP card holder: € 9,00

Groups of 10 (full paying) persons or more: 10% discount (per person)

Address

Tropenmuseum, Linnaeusstraat 2, 1092 CK, Amsterdam

Website: https://www.tropenmuseum.nl/en

Bio

Samuel Aylett is a PhD researcher at the Open University. His PhD analyses shifting representations of empire and British colonialism at the Museum of London from 1976-2007. Broadly speaking, his research interests are concerned with the Museum as a locus for examining the cultural impact of empire and decolonisation in Britain throughout the twentieth century, and how the legacies of empire continue to shape Britain’s past, present and future