One of the joys of listening to Radio 4 is that while having my regular daily walk yesterday I heard a lovely discussion about the 50th anniversary of Jaws, the film that created the summer blockbuster and gave us some top meme-worthy comment.

It feels apposite to mention this because one of my main takeaways from this week’s UK-EU reset summit was the realisation that we are now entering a semi-permanent state of negotiations between the two, which in turn means more work for me and further vindication of my decision to stick with studying UK-EU relations. Truly one of the last jobs for life that people used to have.

Since I’ve been busy having such thoughts, I come late in the day to the business of analysing the various documents produced on Monday: the Joint Statement, the Common Understanding and the one actually-concluded document, the Security and Defence Partnership (SDP; half of which is cribbed from the EU-Japan piece, as Anton Spisak notes) . You’ll also want to read the Commission’s Q&A, since it’s less ambiguous about what’s what.

If you want run-throughs, then I recommend Anton’s piece, as well as David Henig‘s and Steve Peers‘, the last of which is worth quoting at a bit of length for its conclusions, with which I fully concur:

Finally, it’s notable how many Rubicons have been crossed with this reset deal. As noted already, the UK now accepts the market access/integration trade-off. But the EU now accepts agreeing this trade-off with the UK in limited fields: the UK can have one foot several steps up the Barnier escalator, but the other one firmly on the ground. The EU has also accepted a Swiss-like complex legal relationship with the UK, having opposed it in principle for years. (In fact, the EU already conceded this point when agreeing the TCA; but that treaty hid its legal complexity better than the reset deal does). The UK has accepted an agreement with the EU as regards movement of (some) EU citizens; although it might claim this arrangement will simply resemble its youth mobility treaties with many other countries, the extent of that similarity will be dependent upon the details of the final deal. Above all, the EU, having accepted freer movement of some goods and demanded the freer movement of some people, can no longer lecture the UK on cherry-picking or cake-eating – what with all the crumbs and cherry juice smeared across the EU’s own mouth.

Rather than rehashing all these colleagues’ fine efforts, I’ll stick to adding some further thoughts.

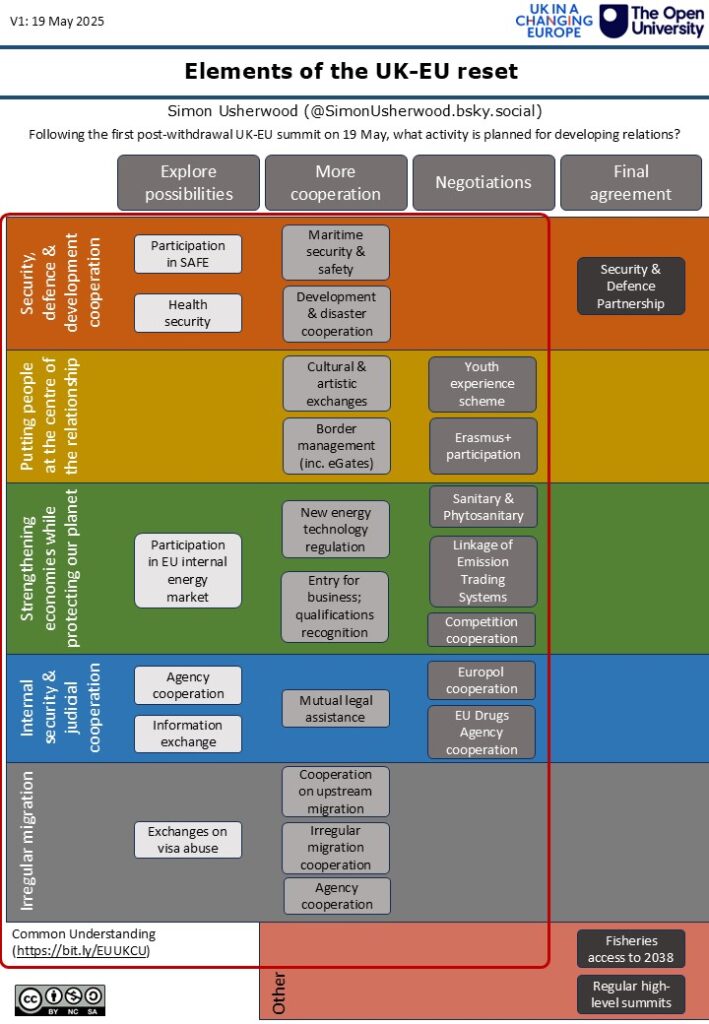

Substantively, the package here is both more extensive than most had anticipated and less developed. Rather than sticking the Nick Thomas-Symond’s three-basket model we have a Common Understanding with five main headings, plus the bits that don’t fit in within them, like fisheries and the very idea of regular UK-EU summits.

At times, this all reads like someone has asked ministries/DGs to throw in anything they’d like to see discussed, which might not be a million miles from how the process went in the UK, but it sets a wide open terrain for negotiation.

And it is negotiation. Barring the SDP, there is not a single final decision. Even the fisheries access that generated much interest in the British press is only a political agreement, with a legal text at least a month away. As I note in my summary graphic below, there are a handful of commitments to negotiate, plus more vague intentions to do more together or to ‘explore possibilities’.

Moreover, there’s not a single date for any of this to happen, even the topics that both sides agree will be negotiated. Therefore an early marker of how much effort is being put into this will be the speed with which the Commission produces and agrees mandates for SPS, Emissions trading, Energy market integration and youth mobility/experience. The speedy release of the competition cooperation text on Tuesday might be a good sign, but equally the fact it wasn’t ready to go with this package suggests that none of this will be easy.

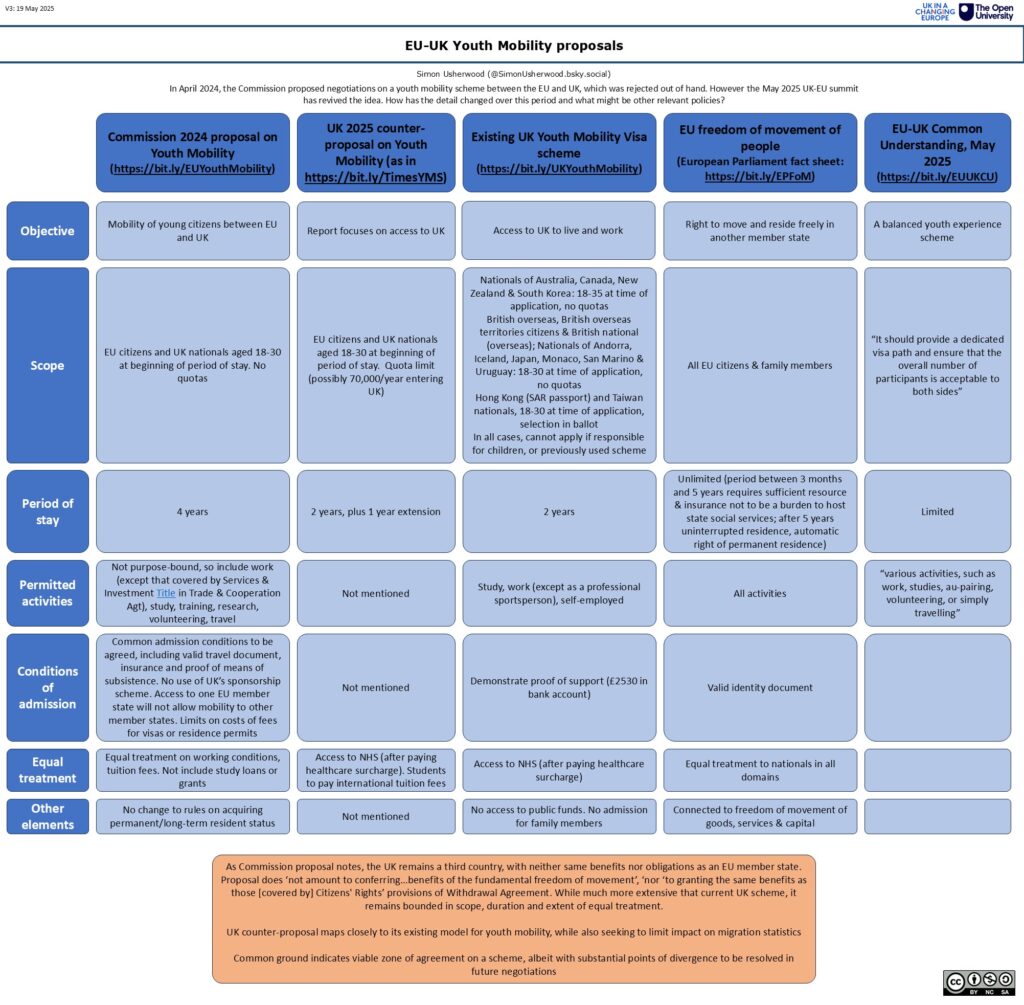

On that point, it’s clear that this is not an era of unbridled euphoria and working together, but regular international relations, with each side pushing its interests hard. The French squeezed on fisheries over the weekend, just as the British evidently got youth mobility/experience parked to avoid more “it’s not freedom of movement” arguments that would just further link that scheme to freedom of movement in people’s minds (as more than one person has commented to me this week).

Indeed, it is the practice of the UK government in all this that raises the most concerns.

Across public policy there appears to be a profound aversion to open policy-making, instead keeping things in-house and driven by focus-group polling. It’s not necessarily wrong, but it does raise the risk of generating policy that lands badly. In this case, the harrumphs from devolved bodies, scrutiny bodies, sectoral interests and others with interest in the matter speak to the consequences.

A case in point is eGates. This was something that has been under negotiation for quite some time, held up by the EU’s delays in implementing the Entry/Exit System and some member states’ quibbles over legal barriers. The government decision to present this as an immediate benefit very quickly fell over in the face of, well, facts and took away from what was still a story that would have been a positive selling point.

If we are now entering a permanent negotiation then the government will need to work more on its narrative around this process. To return to Steve’s quote earlier, this isn’t an escalator back to membership, but equally it’s not clear what the underlying logic is. Put differently, everyone knows the government’s red lines, but it’s not clear why those are red lines.

As more and more cooperation occurs, that will mean more and more instances of the UK becoming a rule-taker: SPS, ETS and energy markets are all explicitly framed this way in the Common Understanding. That creates a discursive tension with the control that has been taken back, which requires some vision of why this works to be articulated.

Therefore, my second big indicator will be the extent to which the government is both able to articulate that vision and the effort it puts into so doing. The three-basket model was evidently a placeholder, but the public statements from Starmer this week don’t offer a replacement beyond the UK ‘being back’.

This will matter when the various negotiations start to come home to roost. While there is no explicit cross-linkage, undoubtedly that will occur at points when it suits one or more of the parties involved: remember too that all of this is happening on top of the previously-described reviews and negotiations within the TCA itself.

Youth mobility/experience is perhaps the most likely flashpoint. The wording on Monday was a classic piece of “we have agreed absolutely no principles or even whether it will happen at all”: as I’ve written for The Conversation, the problems are almost all domestically British ones, even as the EU genuinely struggles to see the issue. But now it’s a totemically-important item for some member states, there will have to be some kind of reckoning.

So, early days on all this.

What matters is partly about political will on both sides, but also about capacity. The lack of interest in European media was palpable, reflecting the low salience of building more ambitious relations with a country with whom the EU already has a serviceable relationship. There has been no public discussion about whether the British machinery of government has the capacity or skills to run multiple, permanent negotiations of a kind that it hasn’t tried before.

Monday was full of good vibes and warm words, but it’s not those moments that will define how the relationship works in practice.