Headaches in the morning

Maybe it’s some kind of Stockholm Syndrome, but since the Tories left office I have not felt the same urge to write about British European policy.

Equally possibly, it might be because I feel a bit broken by another government with a lack of clear purpose in this domain. Labour, like their predecessors, seem to be stuck at the point of realising this whole Europe thing might be a bit more complicated than they thought, so extemporise until they can work it all out some more.

This was brought to a certain head last week for me off the back of some comments I made in an interview. In it, I said:

“The secrecy right now lets others claim he [Starmer] has no plan – or worse, is just looking to make deals where he can.”

Various people have pushed back on this, mostly by reading it as ‘Starmer actually has no plan’. While I’m not quite arguing that, the impression that this is the case seems somewhat self-evident: communication is focused on what won’t happen – free movement of people, membership of Customs Union or Single Market – and on the nebulous ‘reset’.

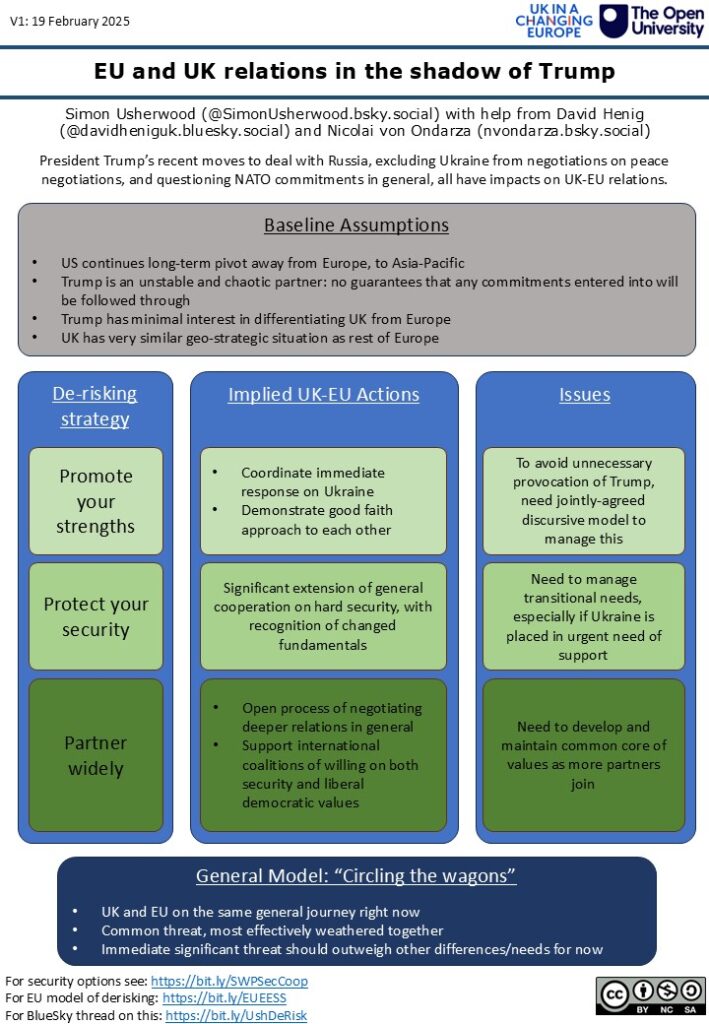

This needs more thought and reflection, because there are several things going on here, all of them consequential and none of them clearly determinant.

First up, we need to be a bit clearer about what we’re/I’m talking about. In the broadest terms, there’s a difference between what we might term a vision, a strategy and a plan.

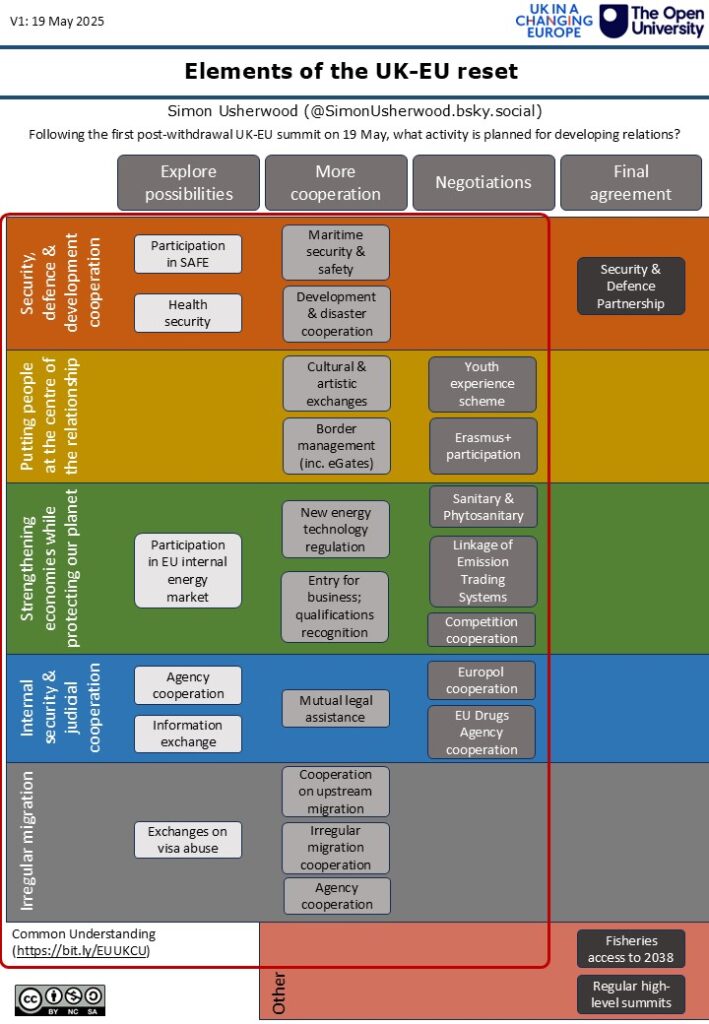

David Henig’s fine piece speaks to this difference by noting that we know what the UK wants of working with the EU; namely cooperation in any and all areas within the envelope of non-membership of the Customs Union, Single Market or full EU membership. That includes the usual litany of items such as an SPS agreement, fisheries access and security.

That is a plan (or rather, a series of plans); specific and localised actions to take. But it’s not really a strategy or a vision.

The UK has long failed to settle on – or even consciously discuss – its vision for relations with the EU and its predecessors. The point of relations sits uneasily in the wider uncertainties of how the UK wants to position itself in the wider world or of what kind of place it wants to be. You can insert your favourite Dean Acheson quote here [although seeing the other two ascribed to him, it might become my least favourite one].

Below any high-minded vision of who we are and what’s our place in the world, there is strategy, which starts to translate down towards the broad thrust of activity. In this case, the questions are whether the current red lines are fixed and whether they derive from some higher purpose or instead are a function of party politics of the last few years.

Put differently, there’s nothing wrong with red lines, but you need to be able to understand why they exist and what purpose they serve if you are to defend them and to use them in your negotiations with the EU.

In this, I’m rather old-fashioned in thinking that party politics most usefully stops at the water’s edge and that external relations should speak to the needs of the country as a whole. But your mileage may vary on this.

At present, the defining mechanism seems to be one informed by the imperatives of trying to neutralise a tricky topic in party political terms, while also recognising specific needs and asks, combining to produce the external relations version of the Woolie’s pick and mix: lots of choice, lots of things you’ve never seen before and not the most sustaining of diets.

Secondly, we have to be alive to why people talk about wanting a vision/strategy/plan.

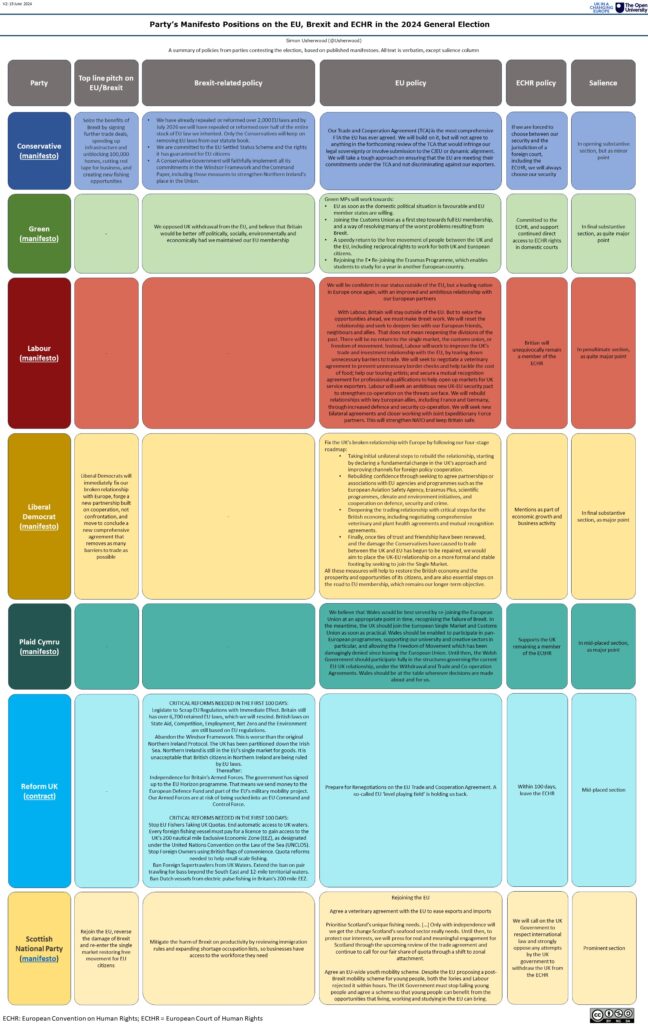

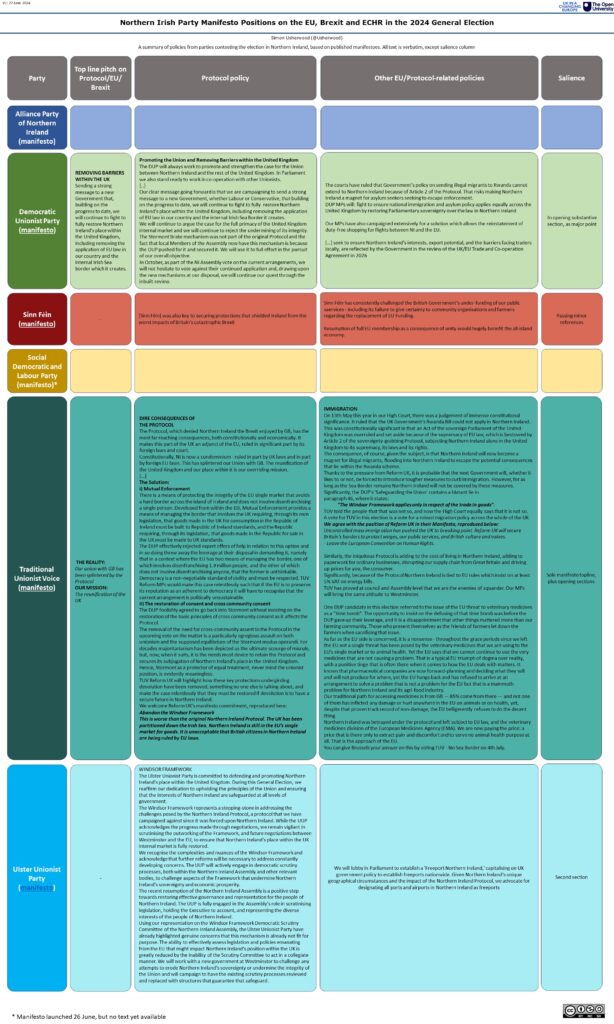

Clearly, the lack of strategy or vision is not for lack of ideas out there. The absence of a more articulated Labour policy has left groups from across the political spectrum to offer programmes and priorities (this is a good place to get some overview).

Because these are typically isolated from the need to attend to the party politics that the government has decided to be hemmed in by, they come with their own visions and strategies.

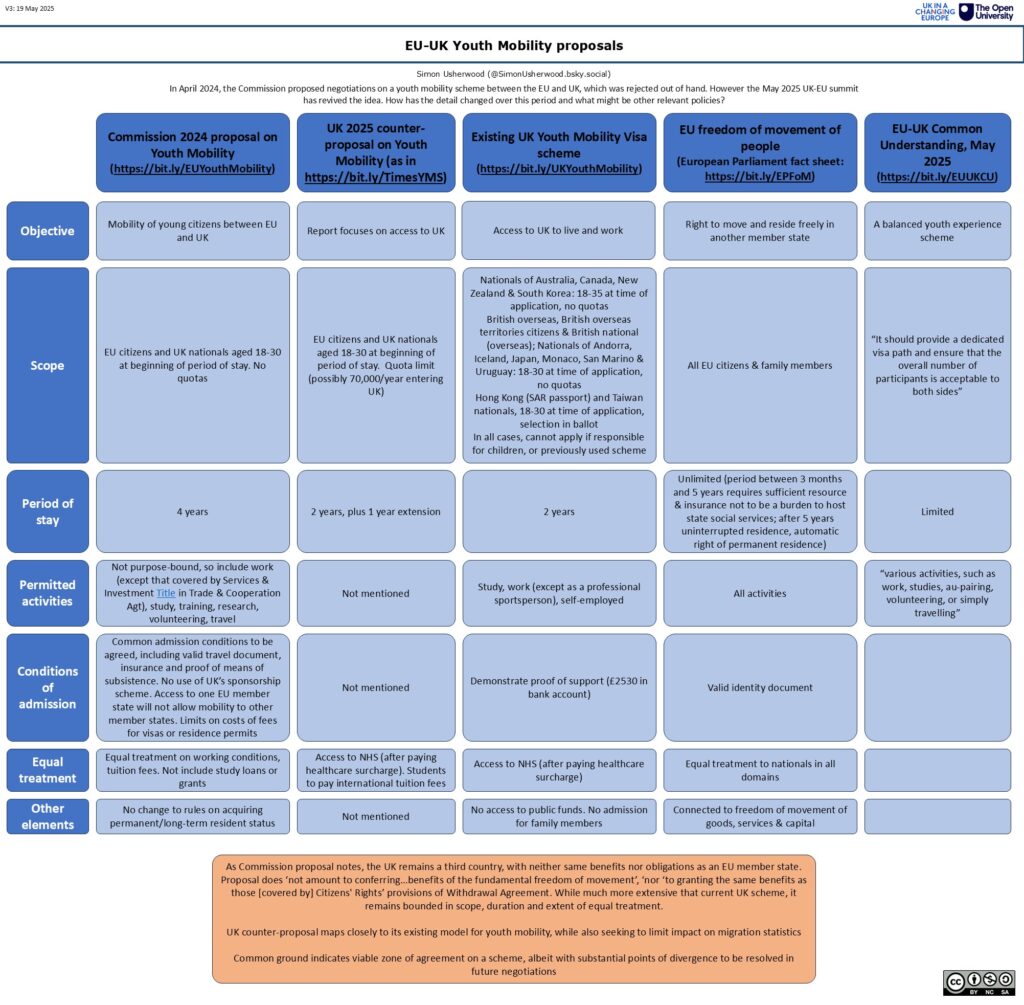

Right now, a lot of that comes from pro-European voices that take doing (much) more with the EU as A Good Thing. The youth mobility impasse has been a recent rallying point for them, both on what they see as intrinsic merits and on wider signalling or a desire to multiply connections.

Even my own position – that the government needs its own vision and strategy to create a durable relationship with the EU – still comes with an agenda of wanting to avoid big swings in policy.

From the government’s perspective, this is a complication: moving on a specific point risks opening up broader implications for relations just at the point when they seem to wish to hold off such things. Hence, havering on youth mobility despite very broad backing from interested groups and public opinion.

Again, this comes back to the lack of a robust vision and strategy that the government can lean on as justification for what it’s doing.

Finally, we have to separate rhetoric and action.

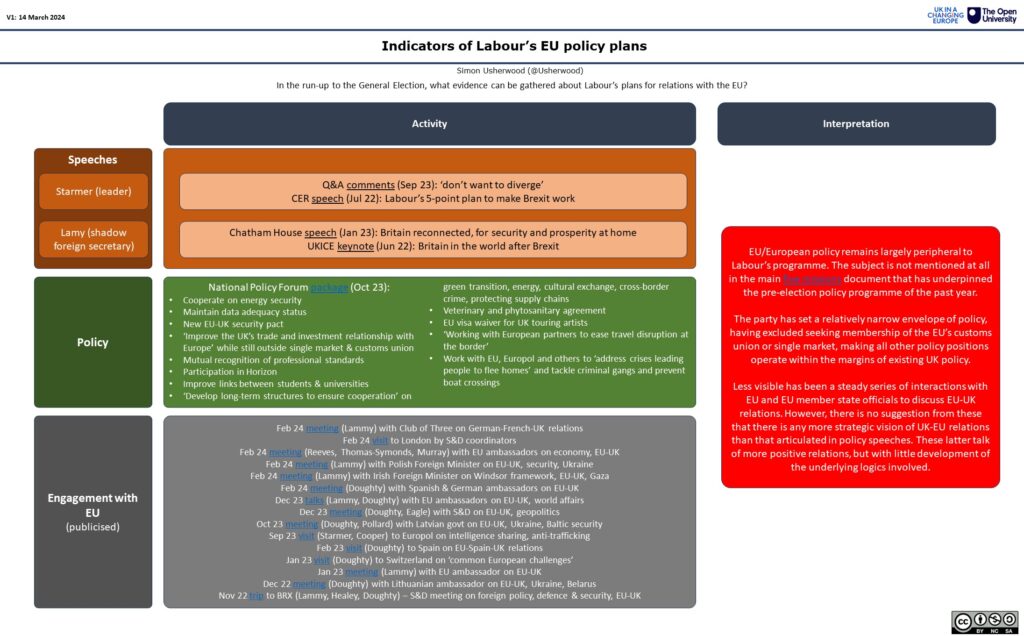

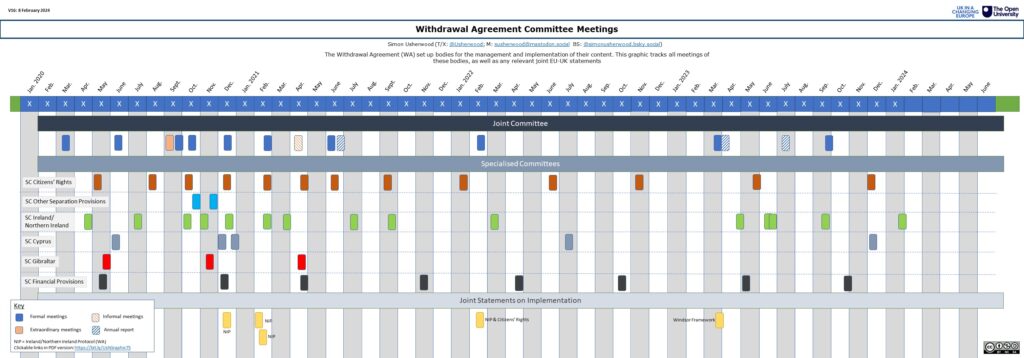

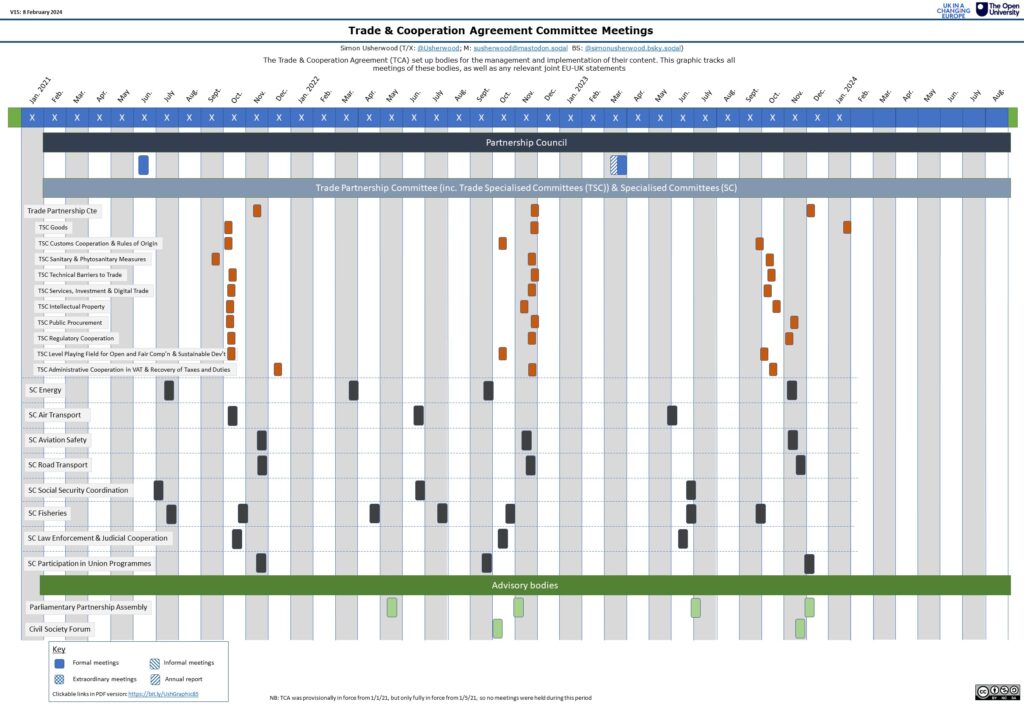

Just because politicians and pundits talk in a particular way, it doesn’t mean that they follow through on that in their action. In the present case, there is clearly a huge amount of interaction and activity between the UK and EU (again, a good overview here).

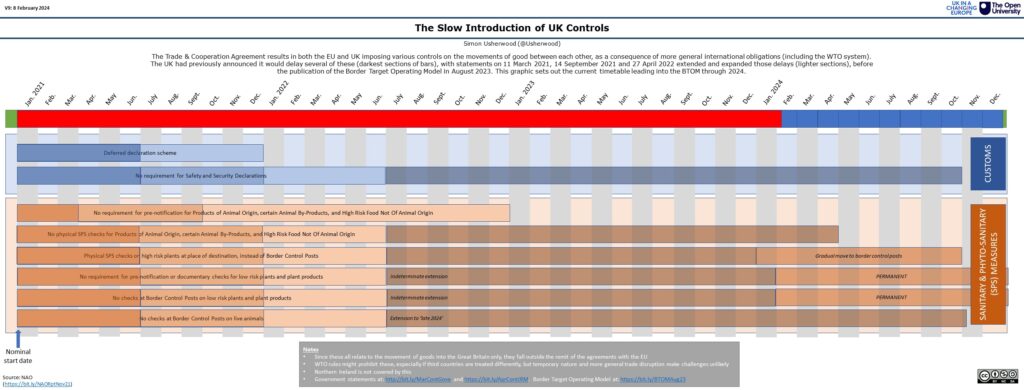

Last year’s fun over EV car batteries is a case in point, where lots of work went into avoiding a mutually-damaging situation: exactly the kind of issue that bubbled along in the specialist media, but which would have been a much bigger problem if not addressed.

To that extent, lacking a strategy hasn’t held back a lot of work, on things that need dealing with now.

But working towards any kind of relationship that is robust and resilient requires more than just reactive management of stuff that pops up. As the 2000-2010s showed very vividly, lots of small choices and steps can lead to radical outcomes: ‘not banging on about Europe’ became ‘let’s not talk about it’, leaving others to fill the gap.

—

To pull all this together, Labour’s issue appears to be not that dissimilar to David Cameron in the 2000s: a desire to park the ‘Europe’ issue and deal with other things that needed attention (and don’t cause so much anguish) leaves the field open to others to make their play for agenda-setting, which probably results in outcomes that are ultimately more adverse for the government than would otherwise have been the case.

This points to the need for finding a happier medium between obsessing and ignoring EU relations. Like any other significant part of public policy, there has to be sufficient engagement to follow through on agendas/visions if that is not to become a point of instability.

Knowing what you aim to achieve – and why – would be a helpful start in determining that level. To delay will only reduce options and make it harder to impose order and stability over the relevant activity.