Back when the Withdrawal Agreement was first concluded, I did wonder about whether there was a need for an explainer for each of the provisions contained within it, one graphic at a time, so that everyone could be more on top of it all.

However, since there was rather a lot going on then (and since I’m not actually a legal scholar), the moment passed.

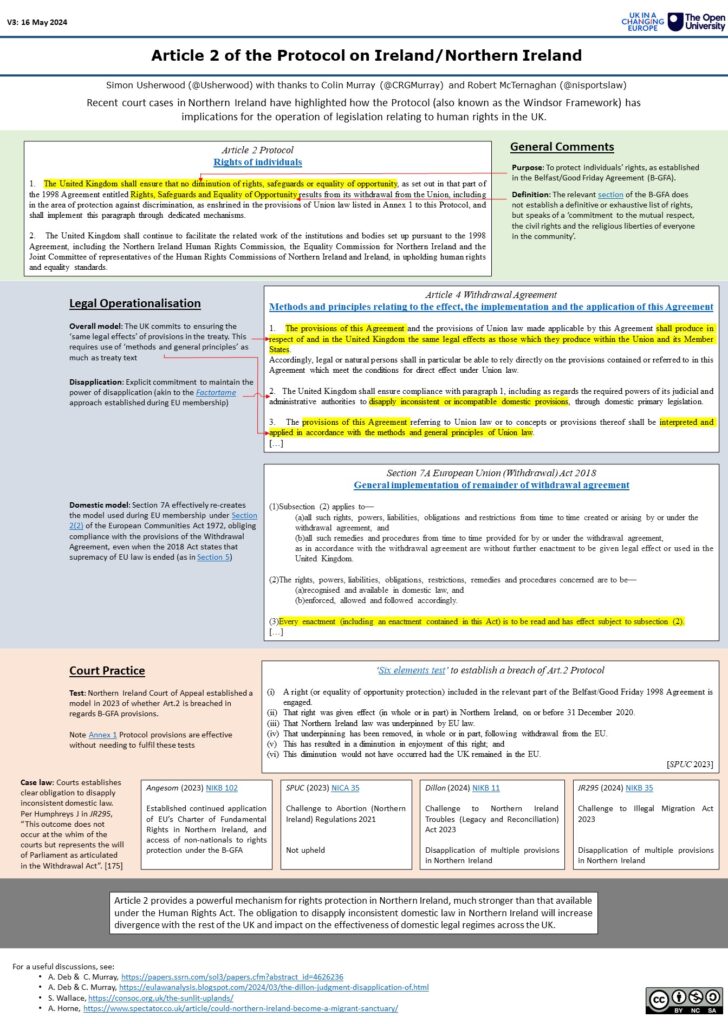

I’m reminded of all this with this week’s featured provision: Article 2 of the Northern Ireland Protocol. What I – and apparently everyone else in London – took as a bit of boilerplate about demonstrating commitment to the Belfast/Good Friday arrangements on rights and safeguards, actually turns out to have some pretty significant implications for the entire UK and UK-EU relations.

The size of the graphic below will flag that this isn’t a simple bit of law, but it’s important to appreciate that the nominal purpose of the Article also drives a general requirement to create effective British legal mechanisms to give effect to the Withdrawal Agreement’s provisions in very much the same manner as was the case for EU law during British membership of the EU.

This shouldn’t really be a surprise, given that the logics of supremacy and direct effect hold just as much in a situation like Northern Ireland – a non-member where many EU laws still apply – as in, say, Ireland – a member.

The commitment given in Art.4 of the Agreement in turn drove the provisions of the UK’s EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018, which make applying the Agreement and relevant EU law over inconsistent domestic provisions not simply a whim of international law but an obligation from Parliament.

The upshot is a very strong mechanism for protecting rights in Northern Ireland, far beyond ECHR or Human Rights Act powers.

However, this has in turn resulted in Northern Irish courts in the past couple of weeks concluding that parts of UK legislation can’t apply in Northern Ireland. This week’s ruling on non-deportation of asylum-seekers was the localised trigger, mostly because unlike earlier cases its effects are felt back in London.

As much as the government has looked to appeal both this and the Dillon judgement, legal opinion suggests that this isn’t likely to succeed, given the extensive and binding legal instruments in play.

While it is tempting to suggest that this is all the consequence of inadequate negotiation of the Withdrawal Agreement, it is more a case of politicians at the time being unwilling to explain the trade-offs involved in creating a bespoke arrangement for Northern Ireland. Once the decision to avoid any north-south border was taken, then it was evident that this would create east-west implications. London’s political bluster obscured the basic choice between east-west barriers or more extensive GB alignment with the EU.

At which point we might note that both Art.4 of the Withdrawal Agreement and Section 7A of the EU (Withdrawal) Act apply across the entire Withdrawal Agreement, not just the Protocol.

PDF (with clickable links): https://bit.ly/UshGraphic128