This week’s vote on the Consent motion was unremarkable enough that there was hardly any media coverage in the run-up, even in Northern Ireland itself.

Positions had been long-known and the result (a simple majority) was a given, despite the (sometimes long-winded) efforts of some MLAs to convince others.

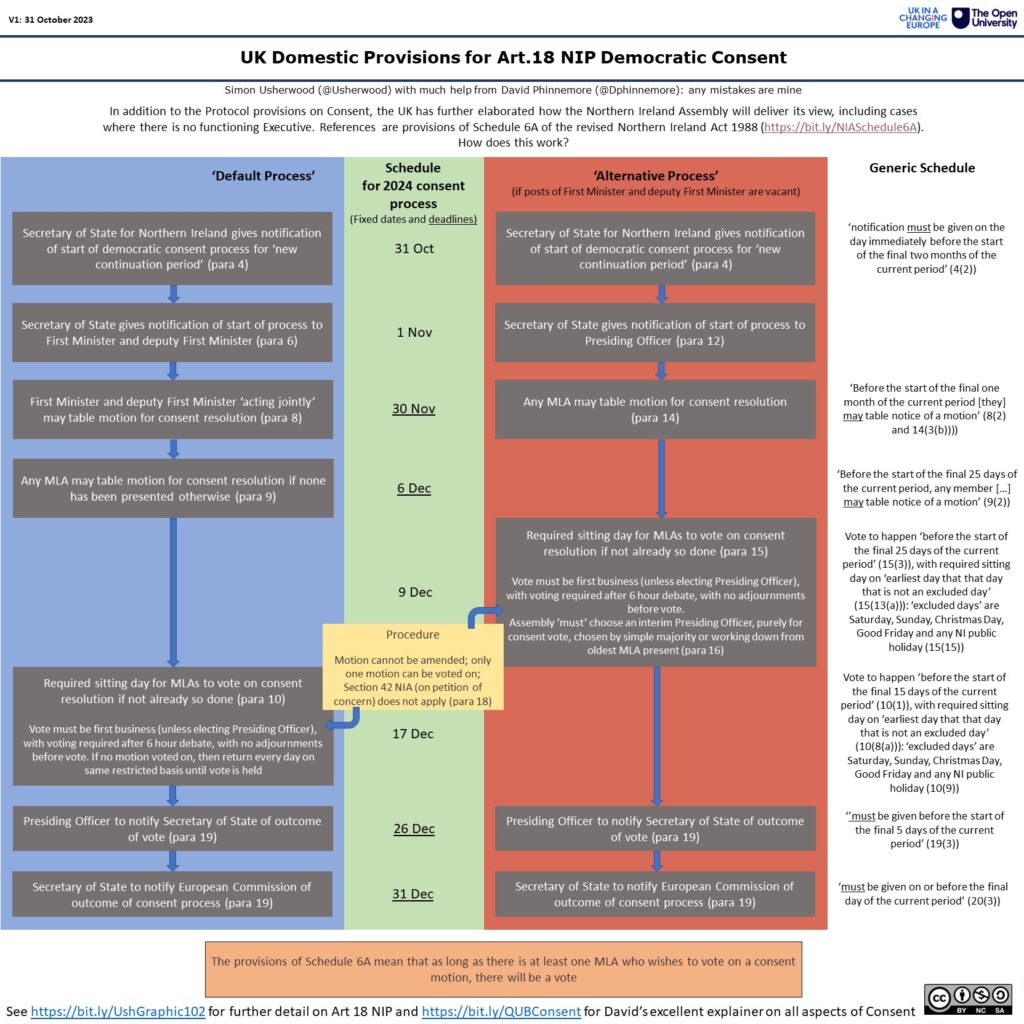

For a mechanism that had raised so much interest back in 2023 in the Windsor Framework, this might be seen as a victory for boring politics.

But to watch the debate unfold – as I did for a few hours – was to be struck by the shallow foundations on which the entire NI Protocol rests. There was scarcely a voice raised that thought the Protocol was a good thing for Northern Ireland.

Instead, those voting in favour of its continuation for another four years spoke of it being a necessary consequence of a decision to leave the EU that had been foisted upon the region by voters in England, and the least bad option among a menu of all bad options.

Likewise, even if Unionist arguments about EU laws being imposed upon Northern Ireland without local agreement were somewhat undercut by others observing that the Unionists had said how wonderful the Windsor Framework would be only 18 months ago, there was still some sympathy for the view that the Protocol wasn’t what Northern Ireland would have chosen for itself.

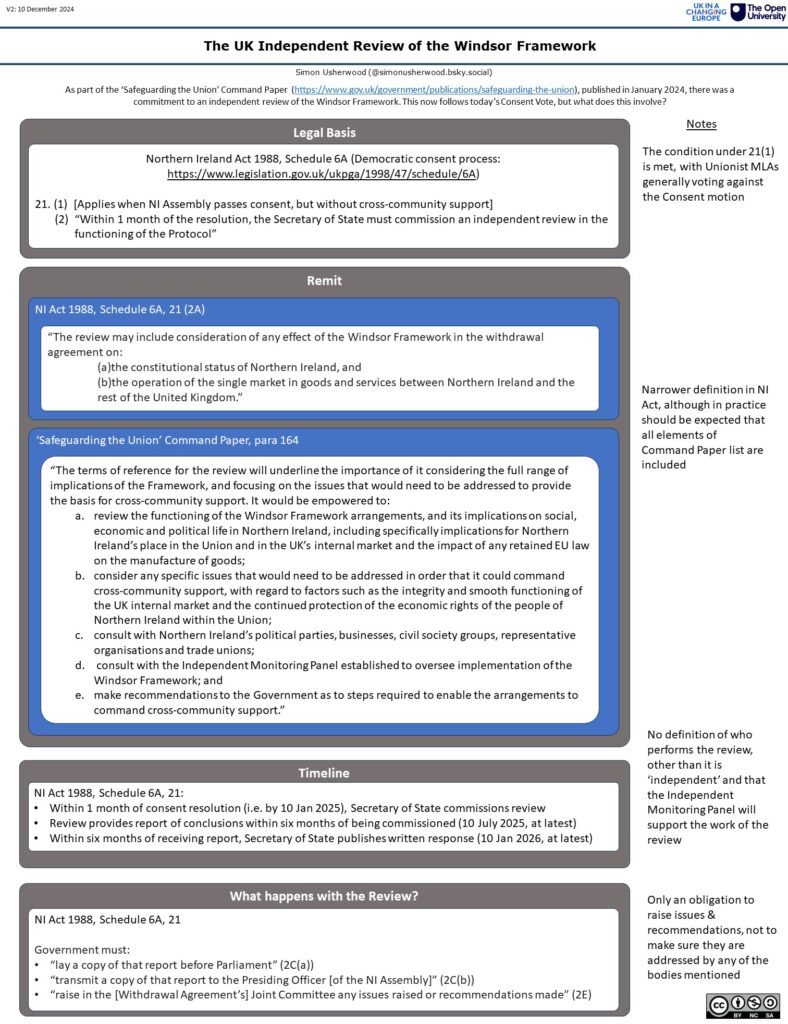

As we now move into the UK’s own review of the Protocol, perhaps some of these dynamics will come out more properly, to allow for the finding of some common ground. But even if Unionists can reconcile with others about what to do, they still need to convince both London and the EU that this is worth reopening a topic that caused so much grief last time around.

Northern Ireland is thus likely to find itself locked into a system that it barely tolerates and in which there is limited scope to build durable accommodations. A fundamental shift in British policy – towards joining the customs union or single market, say – is far beyond the horizon, so the local arena is likely to remain the primary one.

As attention drifts away from Belfast, the danger of an accidental crisis grows: someone in Brussels forgets to check the implications of a piece of legislation; someone in the Assembly doesn’t realise the effects of some routine directive; someone in London fails to connect broader developments in relations to the Northern Irish case.

While I think we can all agree that a return to the ‘hot Brexit’ period is very much to be avoided, that should not blind us to the perils of more mundane relations.