This is a draft version of a piece published in Political Insight. Please refer to that version for any citations.

Even before Covid, it was evident that 2020 was going to be a difficult one for British politics. The December 2019 general election might have given Boris Johnson the majority he needed to push through the Withdrawal Agreement that had bedevilled the past three years, but that merely opened the door to the next phase of Brexit – working out what a new relationship with the European Union might look like.

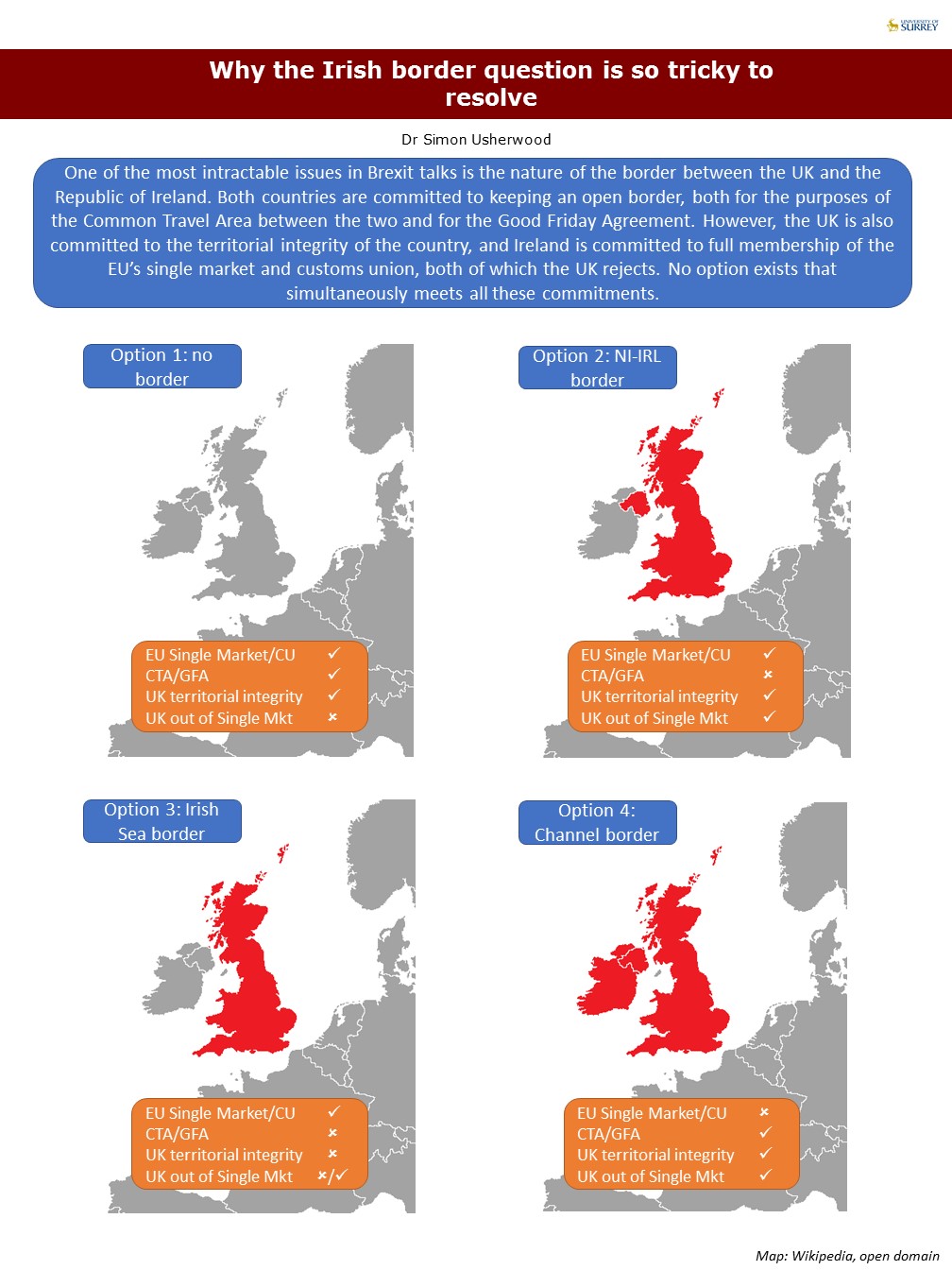

The Withdrawal Agreement was focused on ending the old relationships: finding arrangements to tie up the financial liabilities, securing commitments on citizens’ rights and the Irish border. But it was never meant to be the be-all and end-all of the process. Alongside it, a Political Declaration announced the intention of both sides to pursue a new set of negotiations on an “ambitious, broad, deep and flexible partnership” that would reflect the proximity and importance of each to the other.

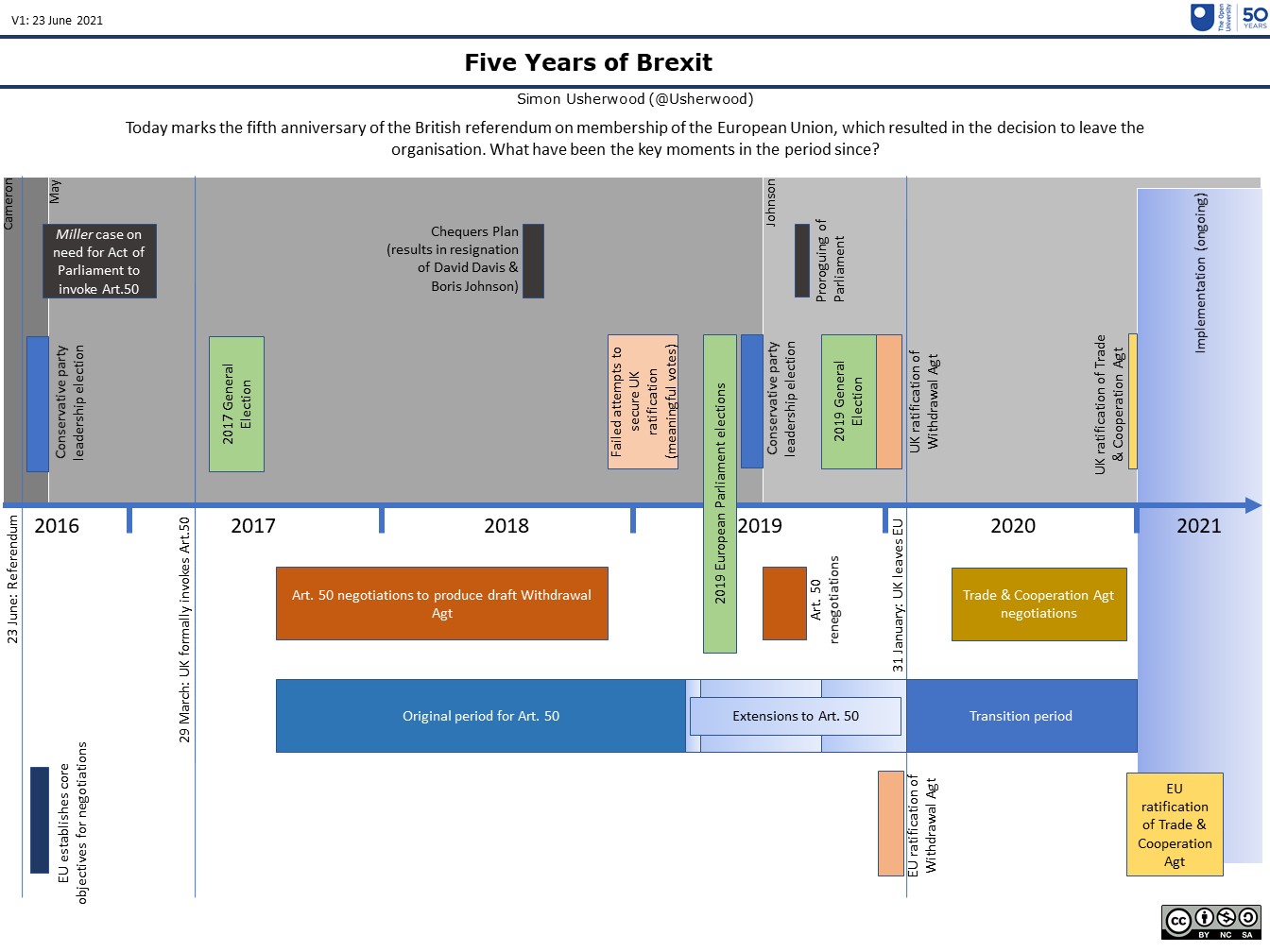

The obvious fly in the ointment was that the repeated extensions of the Article 50 process to produce the Withdrawal Agreement had not been matched by extensions of the planned period in which to conclude this new partnership. The date of 31 December 2020 for the new treaty’s operation had been set in the version that Theresa May failed to get through Parliament for the original March 2019 deadline. Despite having to push that back ten months, neither side seemed keen to flex. For the EU, a delay would have both pushed into a new financial planning period and dragged out a process that was dragging attention away from the other, more pressing items on the to-do list. For Number 10 under Johnson, asking for more time after making so much of the previous delays was simply not an option, especially given the belief that some time pressure could help make the Commission more flexible.

The upshot was that the early spring of 2020 found the two sides preparing to conclude another agreement with each other, of a scale and nature that more usually might take several years of negotiation, a situation that became even more daunting as those talks formally started in March, just as the scale of the Covid pandemic was becoming all too clear.

With this in mind, it is still rather easy to overlook that the conclusion at all of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) on Christmas Eve, just nine months later, is a significant achievement that has no real parallels elsewhere. The reasons for that successful conclusion are worth examining, because they also help to explain the contents of the TCA.

Most obviously, and distinctively, this was a negotiation about divergence, rather than convergence. Almost all trade deals have concerned themselves with reducing barriers between the parties; an often-difficult process of trying to agree on joint standards or processes, or which side’s version might be acceptable to both. By contrast, the UK and EU had shared a vast array of common laws, regulations and procedures and so it was a matter of what they might want to stop doing in alignment with each other, at least in formal terms.

Secondly, the UK made very clear from the start of this phase that it intended things to be kept to a very limited scope. Notwithstanding the rhetoric of the Political Declaration, the formal opening position that was presented in March 2020 indicated that this was to be a modest Free Trade Agreement, with minimal diversions into other areas. Less on the table meant less to be got through.

Lastly, the consequences of not agreeing a deal hung all too clearly over both sides’ heads. While the experience of the Article 50 process had been a difficult one, it did underline the importance of having some functional relationship for both. The prospect of entering 2021 with a collapse of all prior arrangements – with all the attendant uncertainty and disruption – was one that did not ever really seem to be acceptable, even to those in the UK that talked of ‘prospering mightily’ in such a situation. The huge disruptive effects of Covid lockdowns only furthered the arguments of those who said that a second level of disturbance was not desirable.

And yet, for all this, the process ended up being a lot more finely-balanced that could have been.

Central to this was the issue that had made the entire process heretofore so difficult: the UK seemed unable to identify clearly what it wanted to achieve. As with Article 50, much of the official position was about ending particular aspects of cooperation and avoiding others, rather than about articulating a more constructive model of what it hoped for and how it fitted with its wider plans. Thus a key issue throughout was the removal of any role for the EU’s Court of Justice after many decades of support by the UK while a member state for the need for an independent arbiter in disputes. Likewise the unwillingness to maintain any future alignment on regulations, even in areas where the UK has consistently had more stringent requirements than the EU.

Likewise, the segmentation of the process by the EU also meant that it had already secured its fundamental red lines in the Withdrawal Agreement, and so seemed more willing to let the UK chose to walk away. This was certainly grounded in an analysis that the latter stood to lose very much more than the EU did by having a no-deal, and by an understanding that in trade talks the larger party usually gets what they want, but that still assumed a degree of coherent strategizing from the UK side that was not always apparent.

Exhibit number 1 in this was the decision to introduce the Internal Market Bill in the autumn, which including provisions to specifying disapply parts of the Withdrawal Agreement in order to facilitate intra-UK trade. Not only did this endanger the parallel process of implementing the Northern Irish Protocol, but it also called into question the entire architecture of international treaty-making, something that is existential to the EU’s being. While gradually walked back by the UK, with no obvious concession by the EU, it did highlight the dangers for the latter of making further commitments that might be disregarded in short order.

All of which brings us to the Agreement itself.

In content, the TCA is a relatively modest free trade agreement, with some relationship-specific elements added in. Certainly if benchmarked against membership, it represents a severe weakening of the EU-UK relationship, even as it does some eye-catching aspects.

Most noted at the point of its rapid signature and entry into provisional force was the ‘zero-zero’ aspect of trade in goods: no tariffs and no quotas between the two. Most free trade agreements fail to hit this, as specific sectors lobby hard to retain protection from competition: in this case, the status quo ante was one of no such barriers.

However, this does not mean that trade in goods has not been constrained. Both sides now have to impose checks for health and sanitary standards, as well as requiring paperwork to prove goods have sufficient local content to meet rule of origin requirements. This multiplication of steps for importers and exporters not only contributed to short-run disruption in the first weeks of the TCA’s operation, but will continue to add cost to cross-border trade, which should be expected to lessen as a result.

But goods are only a part of economic activity and it is in services that effects will be more evident. The UK pulled back from trying to keep the (somewhat patchy) provision for selling services: this includes recognition of professional qualifications or guarantees about British financial providers being able to supply within the EU, potentially of major consequence for the City. In addition, there seems to be little prospect of developing this area, despite it being one that modern free trade agreements more generally are recognising as important for securing economic gains.

Aside from this trade package, it has been fisheries that have taken much of the limelight, as the EU sought to keep its historic access to UK waters, while the UK tried to escape the failures of the Common Fisheries Policy. Both sides ended up putting a lot of symbolic weight on this topic, far out of proportion to its economic value, mainly because it had much potential for demonstrating the success of each side’s negotiating. The result was, perhaps as a result of this, something of a fudge. While the EU quota does get cut back during an adjustment period of five and a half years, and the UK becomes an ‘independent costal state’ at that time, the TCA does allow the EU to impose tariffs on the UK if its quota gets cut any further. Put differently, the nominal independence does come with some effective strings attached.

Elsewhere, it is the absences that have been more striking. Cooperation on security was largely put on hold, as the UK falls out of most of the police and judicial cooperation systems and intelligence sharing. While work-arounds can be found for things like arrest warrants, these will be both slower and more cumbersome than what came before.

Similarly, the continuation of participation in EU research programmes was more than out-shadowed by the decision to stop being part of the Erasmus+ exchange scheme. As critics rightly pointed out, this has been a key means of introducing young, skilled people to the UK and so making that more difficult will have a negative impact on the kind of economic migration the government says it wants to encourage, while also weakening the soft power that the UK carries in the world. A hurried announcement of a replacement ‘Turing scheme’ by the government merely emphasised the cost and confusion of replacing things that had already been demonstrated to work, while exposing the lack of comprehensive preparation undertaken.

And this will be the leitmotif of the next years: a deal agreed at speed, and with minimal discussion with economic and social actors, is likely to run through more extensive ‘teething difficulties’ than needed to be the case. That phrase, uttered by ministers in the first weeks of the TCA, is likely to seem less and less credible as an explanation as time goes by. As much as hauliers and firms will get to grips with the new border processes, and the regulatory gaps get closed over time, this will not be able to distract from the wider impacts that are going to be felt through the economy and society.

To use the language of what might now be termed ‘early Brexit’, this deal represents the ‘hard’ end of the spectrum. Certainly, it stands well beyond the vision of future cooperation painted by the Leave campaign during the 2016 referendum, where participation in the single market and customs union were portrayed as a good balance of being out, but still close.

The dynamics of the subsequent years has been for an ever-harder, ever-purer form of Brexit; as if any institutionalised cooperation is necessarily and fundamentally suspect. As noted already, the shape of debate has been about escaping the clutches of the EU, a position made easier by appeals back to the ‘will of the people’ to leave: would that not be betrayed by trying to keep by other means those links that were rejected back then?

But to what end? This is now, as it has always been, the central question of Brexit: what is it for? Even now, after two treaties and seemingly endless discussion, it is impossible to pin down what vision the UK has for itself as a society or as a member of the international community. It is just as hard to see a concrete project emerging from Number 10 or the government more generally.

“Get Brexit done” was an effective slogan in 2019 because so many people were tired of hearing about the subject. While the TCA does provide a first step towards achieving that, the public is likely to discover that there’s still a long way to go and many difficult choices to be made: taking back control requires control to now be exercised.