‘How Does Learning Happen?’ Ontario’s vision for education

Continuing our series of thoughts, impressions and feedback from the Sightlines conference series, John Parry reports back on the session he attended which considered the way that early childhood education is developing in the Canadian state of Ontario.

Introducing…

It may have been the end of the day for us in the UK but for our seminar presenters Karyn Callaghan and Kelly Massaro Joblin it was 11am on a bright, near freezing winter’s morning in Canada. Karyn, an Early Childhood academic as well as president of Ontario Reggio Association, and Kelly, an Ontario government advisor on Early Childhood, have been at the forefront of championing change in the early years curriculum within the state over the last six years. Their session promised to reflect on the progress and ongoing struggles connected to shifting the state provision for very young children from the established developmental/’school readiness’ agenda to a more holistic child centred approach.

The context

In order to orientate us listeners and watchers Karyn and Kelly first provided some helpful context:

- Ontario is a state of 14.7m people, so under a quarter of the population of the UK but in terms of land mass over 4 times as big (the presenters live a 15 hour drive away from each other).

- 462,000 pre-school children attend 5500 programmes/ provision across the state. Some provision is directly funded by the state but all settings are licensed by the government.

- A patchwork system exists as in the UK. Families pay subsidised ‘fees’ and non-state provision is run by a mix of profit and non-profit organisations.

- Early Childhood educators are seen as professionals (they must hold a diploma in early childhood education after completing a two year training programme). However the profession remains a low pay sector.

- Children move to Primary school in the year they turn 4 but then enter a two year kindergarten programme that is state funded. There is no assessment prior to school entry.

The established view

Before talking about the more recent changes that have taken place in Ontario’s early childhood education Karyn and Kelly emphasised the powerful foundations that had propped up the system for previous decades. As they talked about early childhood provision being seen primarily as a support for parental employment and preparation for school, it all sounded depressingly familiar. Similarly the curriculum that fed into this established system, known as ELECT (Early Learning for Every Child Today), bore a chilling resemblance with the frameworks that continue to dominate early education in the UK. ELECT, which had been in place in Ontario since 2007, was:

- developmental in principle and structure, defining hierarchical skills in social, emotional, communication, cognitive and physical domains for children aged birth to 8

- used to ‘informally’ assess children and as a checklist of progress to school readiness

- entwined with the system of quality assurance and inspection that determined funding for settings and promoted competition between provision.

Unsurprisingly as Karyn noted ‘the developmental discourse although critiqued has become so dominant that many practitioners cannot consider another perspective’

The shift

Karyn and Kelly then shared the cycle of events and innovations that generated the beginning of the shifts away from this established view to where early childhood education is today in Ontario. As always with fundamental change much could be attributed to the circumstantial, being in the right place at the right time, as to the inspirational.

In 2010 following a change of state government early childhood was taken into Ministry of Education and out of Social Care. At the same time the Ontario Reggio Association was formed, committed to make as Karyn said ‘the possible, visible’. The Ministry under new directorship was willing to listen and visited settings recommended by the Association that were taking a Reggio informed approach. Ministry advisors also accompanied educators from the Association on a study trip to Reggio itself. Two key documents resulted from this extended period of dialogue and shared learning:

‘Think, Feel, Act’ (2013) – a resource document for provision from current research demonstrating the positive impact of Reggio informed approaches.

‘How Does Learning Happen?’ (2014) – a new curriculum framework.

Karyn and Kelly explained that the key aspect of ‘How Does Learning Happen?’ was that it was not a top down imposed framework but was ‘developed out of dialogue and a relationship’. They recollected that even the title caused a stir as it had no ‘air of authority’, it is a question that invites you to think about learning, everyone’s learning.

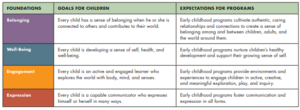

Significantly the new curriculum does not draw on a developmental framework but takes as its focus Engagement, Belonging, Well-being, and Expression, looking at these from the perspective of ‘Goals for Children’ and ‘Expectations’ for settings.

Today in Ontario

Although ‘How Does Learning Happen’ was formally embedded in the pre-school and Kindergarten curriculum in 2016, it has not replaced the developmental ELECT framework but co-existed alongside it. There is still resistance to the new approach often from Teacher Education establishments who teach the early childhood diploma and retain a strong commitment to the perceived objectivity of developmentalism. Karyn and Kelly believe that more recognition was seeping through and that the recent extraordinary events created by the pandemic had reinforced the importance of learning based on relationships. However they noted warily that because early childhood education in Ontario was due for review in 2021, the future of ‘How Does Learning Happen?’ remains in the balance.

Personal Reflection

Looking back at the session it’s hard to imagine what it would take for a framework like ‘How Does Learning Happen?’ to exist alongside the current curriculum in early years in England. With the revised EYFS still appearing to be rooted in compartmentalised areas of learning and an ages/stages structure, that particular window of opportunity for change seems to have passed. In the session Karyn reminded us that Peter Moss has in the past observed that unless the dominant discourse can be interrogated and ‘made to stutter’ new ideas and practices will have little chance to flourish. So as researchers and academics, practitioners, and parents we need to continue to ask those critical questions and make the alternatives persistently visible.