By Jinlan Tang and Shuai Zhang

Introduction

The Modish project aims to track and evaluate a set of interconnected, predicted trends concerning the impact of the growing use of digital/mobile technology (DMT) on regional and local ecologies of teaching, assessment and learning of English (TALE) in Higher Education in the four most populous countries in East and South Asia – Bangladesh, China, India, and Indonesia.

In Phase I and the ongoing Phase II, we collected data in China through teacher interviews and student focus group discussions to explore their perceptions and experiences of English learning, the use of digital and mobile technologies in classroom settings, and in broader educational contexts. In this blog post, we share some preliminary findings from the project.

Student focus group interviews:

From the perspective of EDI, students generally believe that technology has created more learning opportunities, both formal and informal. For example, the widespread application of language-related MOOCs continues to demonstrate their value in facilitating resource sharing through the Internet, particularly benefiting learners from remote areas. As noted by a student, “… open course resources like MOOCs can indeed promote educational equity…MOOCs do promote the dissemination of educational resources to remote areas…” (CH-UNI5-P2-FG-S01). Despite being a relatively traditional form of remote learning, MOOCs remain a significant tool for advancing educational equity and resource accessibility.

With the advancement of digital and mobile technologies, students are increasingly showing greater agency in their use of these tools. For instance, one student shared, “I can use listening apps to hear and memorize words, or listen to English audio, or practice speaking” (CH-UNI4-P2-FG-S02), highlighting their proactive approach in selecting and utilizing specific resources to enhance their language skills. Another student stated, “I enjoy browsing short videos on different platforms” (CH-UNI3-P2-FG-S05), showcasing their autonomy in choosing platforms and content that align with their interests and learning goals. These examples illustrate how students actively navigate digital resources, make independent decisions, and take ownership of their learning processes, which are key aspects of learning agency.

Some students have adopted proactive strategies, such as using translation software to aid their understanding of English-medium instruction in classroom settings. Notably, as the application of large language models (LLMs) continues to expand, students are beginning to use tools like ChatGPT to revise and polish their English essays, assist with academic writing, and even explore potential research topics. As one student shared, “…now students can review their work after class using ChatGPT, generating feedback that teachers can use to prepare for the next lesson, addressing specific weaknesses” (CH-UNI1-P2-FG1-S03).

However, a few students have raised concerns about the accuracy of the information provided and expressed skepticism about the reliability of AI-generated content, showcasing their critical digital literacy skills. These students demonstrate an awareness of the potential pitfalls of relying on AI tools, such as the generation of misleading or fabricated information. As one student noted, “… when I need some reference materials or actual data, what it provides may not be genuine. Instead, it gives me something that seems real but turns out to be fabricated. When I search online, I find that what it provides is not accurate but rather fabricated.” (CH-UNI5-P2-FG-S02).

Teacher interviews:

The data suggests that the level of institutional support provided to teachers may vary across different types of institutions. For instance, at a foreign language university, the interviewed teachers, all of whom work in online education environments, generally say they benefit from favorable policies and actively explore the use of digital and mobile technologies in their classrooms. This is further supported by the community of practice within their institution, where leadership advocates for and encourages teaching innovations and related research.

On the other hand, some teachers report facing challenges due to insufficient funding and policy support in their institutions, which limits their ability to develop high levels of digital literacy. The teaching platforms they use may also require further improvement. This highlights the need to explore more deeply the specific contexts of individual faculties or institutions to understand how external factors, such as institutional support and community practices, may potentially influence teachers’ preferences and practices in technology use.

Conclusion

Given the vast number of foreign language learners in China, as well as the country’s expansive geography—with teachers and students situated in diverse socioeconomic contexts—we believe investigating and understanding teachers’ and students’ perceptions in specific educational situations is important and could provide insights to guide their practice in applying technology.

Moreover, the unique perspective of EDI differentiates this project from existing research that often focuses on teachers’ general perceptions or acceptance of technology. This human-centered concern, with its emphasis on the importance of educational equity, contributes a new perspective in researching the use of technology in education.

Through this project, we have also come to realize the challenges of understanding teachers’ and students’ perceptions. Encouraging them to openly share the difficulties they face in applying technology in their teaching and learning remains an important area for further exploration in the future.

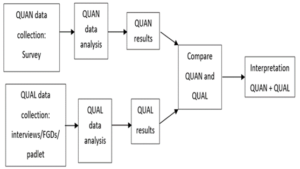

There are four justifications for combining qualitative and quantitative data in this study: triangulation (seeking corroboration between the two sets of data), expansion (extending the breadth and range of enquiry by using different methods), complementarity (elaboration, illustration and explanation of the results from one method with the results from another), and convergent findings (using both data sets to answer the same research question and producing greater certainty in the conclusion)

There are four justifications for combining qualitative and quantitative data in this study: triangulation (seeking corroboration between the two sets of data), expansion (extending the breadth and range of enquiry by using different methods), complementarity (elaboration, illustration and explanation of the results from one method with the results from another), and convergent findings (using both data sets to answer the same research question and producing greater certainty in the conclusion)