Pietra Palazzolo is an Associate Lecturer at the Open University, and has taught a number of OU modules with Classical Studies components. She also serves on the executive committee of the Centre for Myth Studies at the University of Essex, and is a Visiting Fellow there. Along with her Essex colleagues Ben Pestell and Leon Burnett, she is co-editor of a new book, Translating Myth, which was published by Legenda in June 2016. This week we talked to Pietra and Ben to find out more about the volume and their work on myth.

Pietra Palazzolo is an Associate Lecturer at the Open University, and has taught a number of OU modules with Classical Studies components. She also serves on the executive committee of the Centre for Myth Studies at the University of Essex, and is a Visiting Fellow there. Along with her Essex colleagues Ben Pestell and Leon Burnett, she is co-editor of a new book, Translating Myth, which was published by Legenda in June 2016. This week we talked to Pietra and Ben to find out more about the volume and their work on myth.

Q: Congratulations on the publication of your book! Could you tell us about where the idea for the volume came from?

Ben: Thank you. We’re very pleased with how the book has turned out and the job that Legenda has done with it. The idea for the book developed from discussions between Leon Burnett, the founding director of the Centre for Myth Studies at Essex, and a former colleague, Kopal Gautam. Leon and Kopal share an interest in myth and literary translation, and these two areas seem natural companions in the distinct ways they both evoke the migration of ideas across cultures. The theme ‘translating myth’ informed an international conference in 2013 and an MA module before finding lasting form in the book.

that Legenda has done with it. The idea for the book developed from discussions between Leon Burnett, the founding director of the Centre for Myth Studies at Essex, and a former colleague, Kopal Gautam. Leon and Kopal share an interest in myth and literary translation, and these two areas seem natural companions in the distinct ways they both evoke the migration of ideas across cultures. The theme ‘translating myth’ informed an international conference in 2013 and an MA module before finding lasting form in the book.

Q: Your title is Translating Myth, but you explain in the book’s introduction that for you and your co‐editors ‘translating’ means something broader than simply the act of rendering a story written in one language into a different language. Can you explain what other kinds of things ‘translation’ might mean in the sense in which the book’s contributors have interpreted it?

Ben: A myth is always translated: whether from a mythologem or an image or idea. Our experience of myth is mediated through tales or pictures which adapt primordial material. While some chapters in the book look very specifically at instances of literary translation (as in Eliza Borkowska’s illuminating investigation of Blake’s Polish reception), we felt it important to state at the outset that we adopt a broad definition – what is sometimes called ‘cultural translation’. For example, Jessica Allen Hanssen examines the repurposing of Greco‐ Roman myth for children in Hawthorne’s Wonder Book; Sheila A. Spector explores the evolution of Blake’s mythopoeia through his reconfiguration of Christian and kabbalistic motifs; Rached Khalifa re-examines Yeats’s assimilation of diverse mythologies; Terence Dawson charts the twentieth‐century renewal of the Faust myth in Pessoa’s poetry and Jung’s Red Book; and Suman Sigroha considers the reception of Indian myth by European writers. The unifying principle is the re‐emergence and translation of mythic material in new contexts.

Pietra: What emerges from all the contributions to the volume and in our own work as editors is that literary translation and cultural translation work in unison. When considering adaptations of myth, it is impossible to talk about literary translation without considering cultural translation.

Q: The British Centre for Literary Translation (BCLT) at the University of East Anglia recently held a launch for Translating Myth. Could you tell us more about the event and the way translation studies and myth studies intersect in your book?

Pietra: We were very pleased with the Book Launch Symposium organised by Duncan Large at the British Centre for Literary Translation. The event offered the opportunity to explore the links between myth and translation through a series of contributions by Ben Pestell and myself, by Giuseppe Sofo, who contributed the final chapter to the book, and Tom Rutledge of UEA. The event ended with a lively round table debate led by Leon Burnett, where we were joined by another of our contributors, Sharihan Al-Akhras (whose chapter is an impressive study of the Middle Eastern influences on Paradise Lost).

If myth is an act of communication, an experiential act, it is also an act of translation, to use George Steiner’s useful formulation that ‘to hear significance is to translate’. Myth studies and translation studies are cognate disciplines, as they both deal with ways in which translation can be carried out. In applying the concept of ‘cultural translation’ to myth we follow some of the key approaches to translation studies. One, offered by our co-editor, Leon Burnett, proposes the concept of translation as accommodation and reflux. The concept of accommodation takes the focus away from the dichotomy of source text and target text to encompass, instead, a more dynamic understanding of the process involved in translation. In this sense, we can view translations as ‘conduits for cross-currents between native and foreign traditions, whose influence and interaction shape, renew, re-focus and refresh the literary traditions that receive them.’

The concept of accommodation can be aptly applied to myth, since the work of myth entails a transfer of meaning from one spatiotemporal context to another. Our volume reflects myth’s versatility and malleability, its capacity to retain a constant core while showing a high margin of variation, as Hans Blumenberg observed in Work on Myth. The stories of myth relate to specific groups but also travel across periods and cultures.

Q: The book looks at myths from a whole range of different societies, including those from ancient Greece and Rome. Why do you think it is important or interesting to compare the ways in which different cultures use myth?

Ben: Although the word ‘myth’ derives from Greek, the religious or social characteristics of mythology are essentially universal. Yet, as Harish Trivedi shows in his opening chapter on Indian myth, the pre-eminent ‘classical’ status which is conferred on the Greco-Roman tradition has not historically been attributed to myths from other sources. Even now, non‐Greco‐Roman myths tend to be ironically exoticised. Trivedi’s chapter pithily describes a world of myth and religion – and its secular reception – which is as rich and wondrous as the Greek and Roman worlds. Moreover, his reading of the comparative responses to Indian and Classical myths allows us to see the more familiar mythologies in a new light.

Q: For the benefit of our readers who are interested particularly in classical mythology, could you give us a taster of the Greek and Roman themes or stories which are discussed in the volume?

Ben: The book combines an international outlook with a focus on transactions with English or European literature. As such, it is suffused with the Greek and Roman heritage of Western culture. Thus, in addition to Jessica Allan Hanssen’s chapter which I mentioned earlier, we have Leon Burnett’s survey of nineteenth‐century depictions of the Sphinx (of both Greek and Egyptian varieties), which emphasises the pictorial primacy of myth over the narrative element. Similarly, Michaela Keck applies Warburg’s pathos formula to echoes of Pygmalion in Alcott’s A Modern Mephistopheles, while elsewhere Christina Dokou considers structural echoes of classical epic in the poetry of the early years of the United States. Three chapters will be of particular interest to classical reception studies. Emanuela Zirzotti’s discussion of Seamus Heaney’s appropriation of Virgilian katabasis finds Aeneas returning in the guise of ‘Pius Seamus’; Barbara Goff analyses the structural and political implications of Jacqueline Leloup’s Guéidô, which relocates Oedipus to Cameroon; and Giuseppe Sofo’s concluding chapter follows Derek Walcott’s stage Odyssey as it undertakes a further voyage into Italian, illuminating Walcott’s revivification of Homeric dialect techniques.

Q: What else have you got planned at the Centre for Myth Studies, and where can our readers find out more about the Centre’s work?

Pietra: The Centre for Myth Studies promotes the study of myth with weekly sessions of the Myth Reading Group, together with open seminars, international conferences and publications. We would be very happy to hear from people and institutions interested in myth and mythology from an interdisciplinary perspective. We would especially welcome suggestions for topics to discuss at our reading group. The format we use in these sessions is quite informal, with a short presentation (up to 30 minutes) addressing the theme we have each term, followed by group discussion. Our theme for the Spring term is ‘Journeys’, understood as journeys within myth and in mythical tales as well as in relation to the way texts or mythical objects—such as the image of the Golden Fleece used in our call for proposals—travel across cultures and historical periods. Our next theme, for the Summer term sessions, will be ‘Myth and Magic’, and we would be delighted to have proposals from anyone who is interested either in the intersection between these two dimensions or in interrogating the possibilities of such a connection.

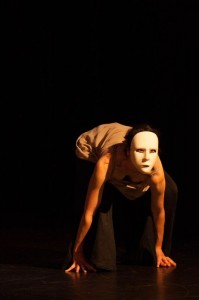

In addition to weekly meetings at the Myth Reading Group, we also organise open seminars and special events. Our latest event was a performance of ‘Babayaga’s Daughter’ by storyteller Sally Pomme Clayton followed by discussion about the forest in Russian fairytales. This year we are planning a one-day symposium entitled ‘Translating Eurydice’ to be held at the University of East London (Stratford campus) in the autumn.

Our centre has an active presence on social media with Twitter and Facebook accounts, and a dedicated WordPress website. If you wish to keep track of our events, I recommend that you subscribe to our website, and send us an email to be included in the mailing list ([email protected]). We are also very interested in networking with scholars and institutions working on myth and mythology across disciplines, cultures, and periods.

Bibliography

Blumenberg, Hans, Work on Myth, trans. by Robert M. Wallace (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985)

Burnett, Leon, and Emily Lygo (eds), The Art of Accommodation: Literary Translation in Russia (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2013)

Steiner, George, After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975)