A couple of years ago, we ran a blog post which shared some of our favourite ‘classical’ holiday destinations; this year, we thought we’d gather a few suggestions from colleagues in Classical Studies for classically-themed ‘days out’ in the UK! The summer holidays are now upon us and, whether or not the weather is kind, there are lots of good ideas for days out at archaeological sites, museums, exhibitions, and more. Here are some of our ideas, but we’d love to hear yours too…

York (as suggested by Emma Bridges)

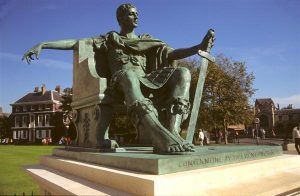

It’s not difficult to find a reason to visit the beautiful city of York, but for a classicist the city once known as Eboracum is a great place to spot some Roman remains. Try navigating your way around the city with the help of this Roman York walking tour and podcast; be sure to take a look at the city’s best preserved Roman fortifications and Roman coffins in the Museum Gardens as well as Philip Jackson’s 1998 statue of Constantine, the first Christian Roman Emperor. It’s also well worth dropping in to the Yorkshire Museum (where OU PhD student Adam Parker is Assistant Curator of Archaeology); the museum hosts, among many other treasures, a fine collection of Roman artefacts, including a mosaic floor. And if you visit York’s Art Gallery before October, you’ll find an exhibition of works by Albert Moore, many of which have a distinctly classical theme.

York’s one of those places where almost every new building development turns up some Roman finds, but even those who don’t know one end of a trowel from another can get a taste of life as an archaeologist by visiting DIG museum, which gives children a chance to become trainee ‘diggers’.

The city famously has 365 pubs, one for every day of the year, but if you’re after some refreshment in a classically-themed location the watering hole for you has to be the Roman Bath pub in St Sampson’s Square; its basement houses York’s Roman Baths Museum.

Hepworth Gallery (as suggested by Jessica Hughes)

My No. 1 summer day-trip recommendation is the Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield, recent winner of the Art Fund Museum of the Year 2017 Award. The Hepworth Gallery is a really beautiful space, with its big windows looking out onto the canal and busy road beyond. In addition to its temporary exhibitions (currently showing is Howard Hodgkin: Painting India), the gallery also has a unique permanent collection which includes works by Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and other modern British artists whose paintings and sculptures often resonate with classical antiquity in some way. When I visited last month, I particularly enjoyed looking at a display of ancient artefacts (including Cycladic figurines) that Barbara Hepworth owned, and at the new display of books selected from her personal library. These included an annotated dual-language text of Sophocles’ Electra, several other translations of Greek tragedies, and a number of books on Cycladic and Classical art.

Wakefield is well-connected by train (approximately 2 hours from London), and you can get a taxi to the Hepworth from the train station. There’s also car parking over the road, and a very nice cafe and bookshop inside. The Hepworth Wakefield is part of the Yorkshire Sculpture Triangle, together with Leeds Art Gallery, the Henry Moore Institute, and the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. The National Coal Mining Museum for England is nearby.

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (as suggested by Jan Haywood)

One of my favourite places to visit is Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery (conveniently located in the centre of the city, in easy walking distance from the railway stations) which houses a world-class collection of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, a group of works from the later half of the nineteenth century that drove against contemporary artistic trends through their admiration for medieval Italian art. Many of these artworks display clear affinities with the ancient world and/or portray famous classical figures. Indeed, be sure to catch Frederick Sandys’ arresting portrait of the magician and princess Medea (1868), which imagines the enchantress preparing a foul potion of magical ingredients. Amongst the many other highlights is Sir Edward Burne-Jones’ fascinating Troy Triptych (1872-1898), an unfinished work that represents several scenes from the Trojan War story.

Maiden Castle (as suggested by Jo Paul)

One of my holiday destinations this summer is Dorset; as a child, I spent every summer there, and I’m now looking forward to showing my own children the place that introduced me to ‘the Romans’ before I had any idea who they really were. There may not be very much to see at Maiden Castle, besides the vast ramparts and the minimal remains of structures like a 4th century CE Romano-British temple – but the sheer scale of the place (the largest Iron Age hillfort in Britain) is impressive. Walking across the ramparts and up and down the slopes (manageable by all but the most reluctant children!) affords spectacular views across the Wessex countryside, and it’s not hard to imagine the commanding position once held by this fort. As a child, I was captivated by tales of how Vespasian attacked it during the invasion of 43 CE, and though this version of events is now disputed, Maiden Castle still offers an intriguing and evocative insight into the earliest phases of the Roman conquest.

The wild landscape of Maiden Castle can be placed in historical context with a visit to the Dorset County Museum in Dorchester (ancient Durnovaria), which houses many finds from the site, including some famous skeletons bearing the signs of injuries which may or may not have been inflicted by invading Romans. Also in Dorchester, you can visit a fully exposed Roman ‘town house‘.