This is the second in a series of blog posts looking back at the history of the Department of Classical Studies at the Open University, on the occasion of the OU’s 50th anniversary. The first post, written by Professor Lorna Hardwick, gave some fascinating insights into the early days (‘50 years in the OU‘). In this second post, Professor Chris Emlyn-Jones shares some of his memories, picking up the story from 1979 – the year in which he joined the university.

*********************

Lorna Hardwick has given an incisive analytic survey from a broad perspective of the development of Classical Studies in the OU over the last 50 years. She was in it more or less from the beginning, and rather than unnecessarily trying to cover the same ground I would like to consider a limited selection of aspects of the early years from a personal (reminiscing, but I hope not too self-indulgent) point of view.

My entry into the OU was 10 years into the 50, in 1979. I had been teaching conventional Classics for 10 years in the small Welsh University College of St David’s Lampeter, and was keen to expand my horizons (not to mention my wife’s desire to live somewhere with more job opportunities, and less remote than West Wales). Moving from what was probably the smallest to the largest University community in the country was expansion with a vengeance; I knew very little about the OU and unlike Lorna had not previously been an AL (what we then called a tutor). So I was moving from a fairly comfortable rural existence into the unknown. For some reason, and I think surprisingly, my ignorance of the OU at interview didn’t prevent me getting the job, though I now gather from Lorna’s blog post that my redbrick degree might, unknown to me, even have denied me an interview, since I have been amazed to learn that she had to fight off a move to restrict interviewees to Oxbridge graduates! Like Lorna (see her blog post) I encountered other instances also where this most revolutionary of institutions clearly still thought on traditional lines.

As lecturer in Classical Studies I had the strong feeling of parachuting in medias res into what I discovered was clearly an evolving pattern of study, in which distinct Arts disciplines were combining in new and stimulating ways. I also discovered I was a junior replacement in the Classical Studies area for the retiring Dean of Arts, John Ferguson. Ferguson, the first Dean of the Faculty and Professor, was qualified in Classics and Theology and had obviously been concerned that elements of both should be part of A100, the first Foundation Course (see Lorna’s blog post). Ferguson’s plan that Classical Studies should maintain a 2nd level presence with 30 point Interdisciplinary courses in both the Greek and Roman periods was not everywhere favourably received after his retirement, and shortly after I joined Lorna and I had to fight off an attempt at Arts Faculty Board to reduce this offering. On the assumption of some colleagues that I had been brought in on Ferguson’s retirement simply to ‘mind the shop’, predatory eyes were cast on our little empire, and a colleague from one of the bigger departments, attempting to reassure me that I’d still have a job in a couple of years’ time, kindly consoled me with the thought that Classics would always be useful as a service department to teach Greek Philosophy, Classical Background etc., to aspiring philosophers and students studying Renaissance literature! Not knowing quite what to do with us, the Faculty placed Classical Studies (the core department being simply Lorna and myself) with Religious Studies in a Working Area Group, an arrangement which didn’t ideally suit either party, and least of all the Dean, Arthur Marwick, whose job it was to chair it.

The absence of students on campus took a bit of getting used to. As a Central Academic it was difficult to spend time, face-to-face, with students (very different and from much more varied backgrounds than the 18-21 year olds I had previously taught). And in the early years, no email! Taking a regular tutorial group in a Region was only rarely possible if one was not displacing an existing or potential tutor. The teaching alternative was two weeks of Summer School, which actually turned out to be a very fruitful experience. As there was no Classical Studies element in the new Foundation Course (A101) this meant teaching subjects at the A101 Summer School in which I was not formally, or only partly, qualified. In my case it was modern Philosophy, which involved tutorials on ‘scepticism and sense data’ (not in my opinion the ideal introduction to the subject for OU students, but fashionable in the 1970-80s). One military student obviously felt the whole subject to be highly subversive: N.B his interesting take on Dr Johnson’s ‘I refute you thus’—‘if I were to take this chair and hit you over the head with it you’d bloody well know it was real, wouldn’t you?’ He never actually carried out his threat and Summer School was most enjoyable, a vital link with the variety of actual OU students which, sitting in relative isolation in Milton Keynes, it was only too easy to miss. And one particularly useful period was spent as a stand-in Staff Tutor in Region 6 (West Midlands), allowing Lorna, the actual Staff Tutor, to take study leave. This involved day-to-day contact with students, Regional colleagues and, in particular, organising weekend Day Schools, involving close liaison with tutors. I also had invaluable experiences as a visiting teacher to day schools in various regional centres around the UK, including, memorably, a fascinating tutorial visit to Ulster’s Maze Prison (1980s) which, because of tight security, took longer for a visitor to get in and out of than the actual duration of the tutorial (on Thucydides, I remember); when I went out for my lunch break the students apologised most politely that they were unable to accompany me.

One of Classical Studies great strengths in the numbers game of University politics in the early days, and ensuring our survival, was our success in generating interest in the Ancient World among students moving from first to second level and so attracting substantial enrolment. The two courses which I was first involved with helping to devise, A293 (Rome: the Augustan Age) and A294 (Fifth Century Athens: Democracy and City State) gave us a chance to build on and develop the Foundation level skills of closely studying primary source material, both written and visual, in a new and challenging context. A key resource for this was the development of the recording of extracts from texts (historical, poetic, dramatic performance) on audio cassette with stop/start facility enabling students to engage in detailed interactive analysis (I remember using this to some effect with analysis of Augustan poetry in A293). We were also able to use audio to interact with TV, for example, studio discussion of Tom Paulin’s TV play ‘Seize the Fire’, based on Prometheus Bound (A294 TV Programme—for illustrations see Lorna’s blog post). Use of Video-cassette, allowing the same level of analysis of TV, and making it unnecessary for students to stay up to watch programmes when the Beeb put them on in the small hours, came in a bit later, after considerable University discussion over whether students should be required to go to the expense of buying a VCR, the clinching argument in favour being that many students were getting their beauty sleep by recording the programmes anyway! (One of my more bizarre experiences: attending a Classical Association conference (late 80’s/early 90’s?) in order to speak on the subject of ‘teaching OU students with video-cassette’ only to discover that their machine wasn’t working. I don’t actually remember how I got through the session; Lorna may—I seem to remember she was there!)

Much of what we did may now seem rather quaint from the perspective of colleagues working in 2019: but remember, this is still the (pre-digital) 1980s!

You might be wondering how Lorna and I working alone managed to cover the spread of disciplines involved in interdisciplinary courses like A293 and A294, and of course the answer is we didn’t do it alone: we had the valuable assistance in A293 of Jennifer Potter on the later Julio-Claudians, Beryl Bowen on Augustan painting and sculpture and Tony Lentin of the History department, who deployed his acute forensic skills in deconstructing the subtle propaganda of the emperor Augustus’ Res Gestae. Colin Cunningham of the Art History department, an expert in Victorian visual culture, but actually a renegade Classicist, presented material on Architecture and Town planning and was an expert TV performer. We were fortunate in securing other distinguished external consultants to provide provincial case studies, notably E. Mary Smallwood on Judaea. One of the OU’s valuable assets, of which we made considerable use, was the BBC, which had its own branch at Milton Keynes, housed on the site of what is now (or was when I last looked) the Faculty of Arts. This association gave us the enviable opportunity of making programmes in which we were able to bid for quite extensive financial resources (on which envious eyes may now be cast). We were also particularly fortunate in securing the expertise of BBC producers who were able to move with us from course to course and so became integrated members of the Course Team and very familiar with the material on the ground and our key aims and objectives. In both A294 and A295 (Homer: Poetry and Society) on both TV and audio we had the great good fortune to work with Tony Coe and Mags Noble, two outstanding producers who not only became very familiar with the material but also brought a vital media perspective to bear on what we were doing. (One of Tony’s great moments, I remember, was when he was asked by one of our consultants in Athens where he had taken his Classics degree!).

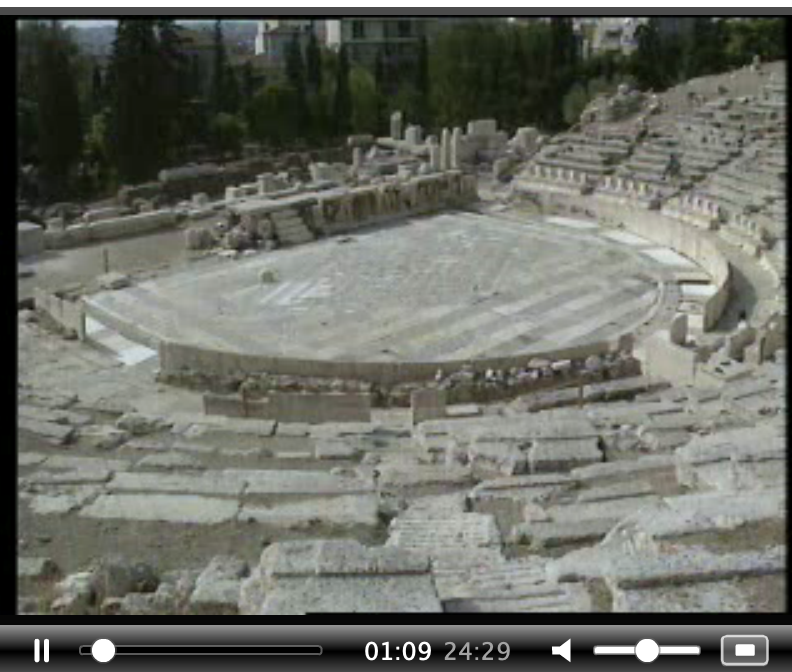

The theatre of Dionysus, Athens, Orchestra and Theatron from A294, TV 2 (‘The Theatre and the State: Archaeological reconstruction’). Presenter Chris Emlyn-Jones, Producer Tony Coe, Production Assistant, Mags Noble. The programme combines evidence from the plays of the 5th century Athenian dramatists with on-site investigation of the extant (largely Roman) remains of the area where they were first performed, in order to reconstruct the probable nature of the original 5th century BCE theatre.

As a result we were able to give students detailed visual experience of important Classical sites, but from unexpected points of view and from unusual perspectives: for example, in a programme supplementing an A294 block on the Greek Theatre, as well as the well-trodden route along well-known sites like the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens and at Epidaurus, students were introduced to an unusual and interesting perspective by an exploration of the (by Epidaurus standards) unusual Greek theatre at Thorikos in Southern Attica, which was linked by Colin Cunningham to a study of the silver mining district of Laurion, a valuable source of wealth for the Athenian polis.

The late sixth century BCE theatre at Thorikos in Southern Attica, from A294, TV2 (‘The Theatre and the State: Archaeological reconstruction’). Presenter Chris Emlyn-Jones, Producer Tony Coe, Production Assistant, Mags Noble. Besides diverging in shape from the ‘standard’ Epidaurus model, the theatre’s link with silver mining is revealed by the rectangular light structure in the background to the left of the theatre, a restored washery for concentrating silver ore.

Likewise, in our course A295 (Homer: Poetry and Society) John Purkis, a Staff Tutor in the English Department, kicked off the course on the Odyssey by linking a detailed survey of evidence on the ground on the island of Ithaka, legendary home of Odysseus, to traditions developed in Homeric oral poetry and story-telling more widely, in British, European and Indian culture. In this same course, we were also able film in detail the ancient site of Troy, and how its importance as a focus of Homeric legend can be related to its position in the surrounding landscape. This was a project in which I was closely involved, and I much enjoyed interviewing the archaeologist, Donald Easton, and Professor Manfred Korfmann, who inaugurated a multi-disciplinary approach to the site, including Greek archaeologists and pre-historians.

Interview with Donald Easton by CE-J from A295, TV, ‘Troy, Reading the Site’. Presenter Chris Emlyn-Jones, Producers, Tony Coe and Mags Noble, Production Assistant, Carole Browne. The programme attempts to relate the complex settlement layers of the citadel of Troy [as the site was in the 1990’s] to the literary evidence for the Trojan conflict. Easton’s significant contribution was a meticulous reconstruction of the evidence in the light the notorious north-south excavation trench, dug in the late 19th Century by Heinrich Schliemann, the discoverer of Çanakkale as the site of the citadel.

*********************

The 1990’s saw a decisive expansion into a formation present colleagues might recognise: we finally became a department, with Lorna as the first HoD. And we gained a number of new colleagues: in 1993 our first new departmental colleague, Janet Huskinson, was appointed, followed by Paula James and later Val Hope, Lisa Nevett, Phil Perkins, James Robson, Trevor Fear and Naoko Yamagata (apologies for not getting precise order and dates of entry—my memory is not what it was). This meant a radical strengthening of the Roman side especially in social and art history and archaeology and a move into 3rd level with a major Roman course AA309 (Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire). And we were also able, finally, to offer courses in both languages. And the department succeeded in getting top marks in the Teaching Quality Assessment of 2001 (however, as Lorna has made clear, apart from the kudos, much good did it do us in material terms!).

If by this stage (early 2000’s) not a mighty oak, then an extremely vigorous sapling. But this has gone on quite long enough—I hope others will take the story further.

by Chris Emlyn-Jones

*********************