Courtney Ince ~ Learning Designer

I recently had the pleasure of working with a module team that were designing a Level 2 undergraduate art history module called Art and Life before 1800. It’s a particularly complex and ambitious thematic module that forms a pivotal stage in a new named degree pathway. It aims to incorporate active learning and inclusivity alongside a radically decolonised curriculum. It is the first full module in art history that students will study on the new named degree.

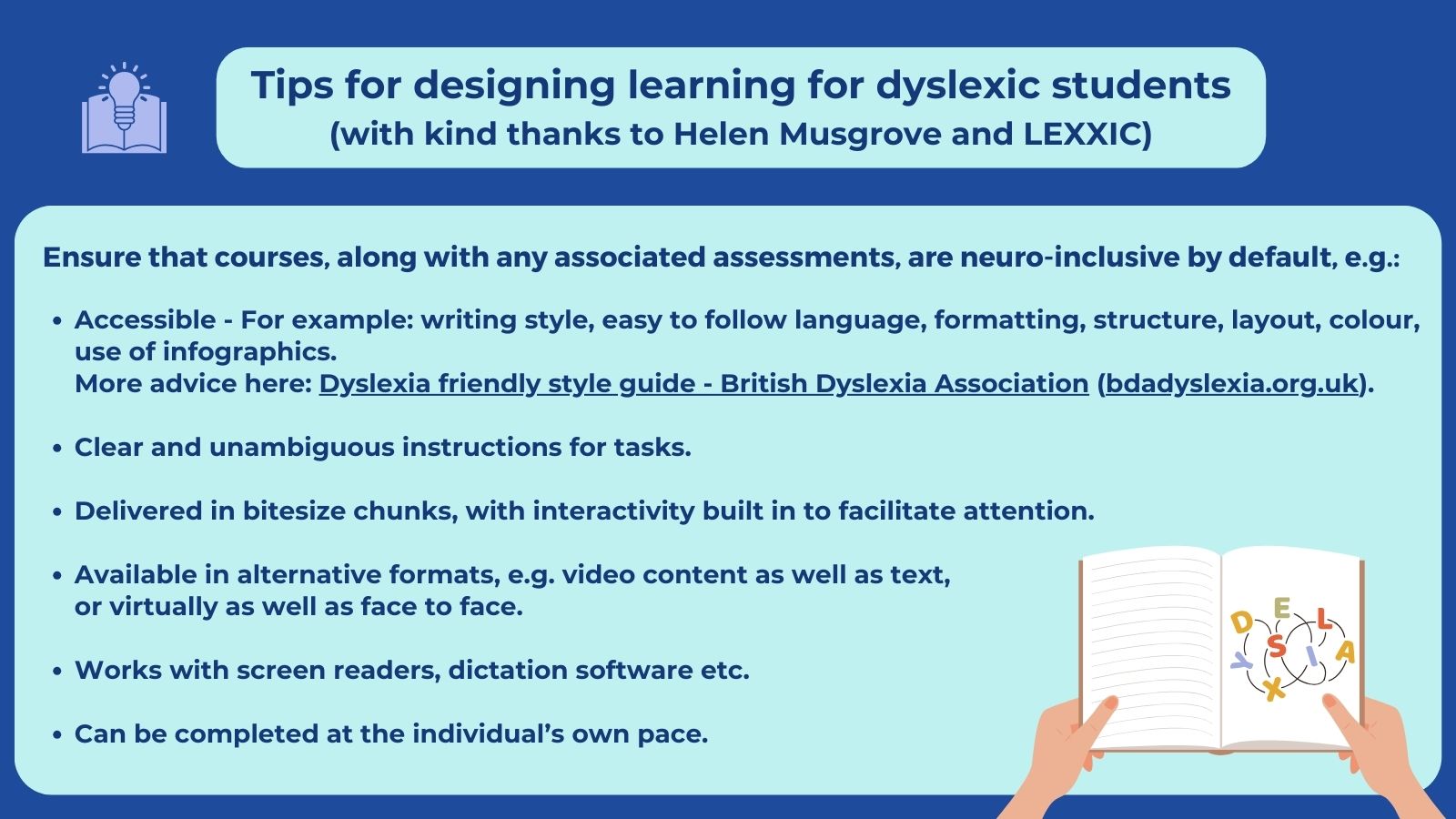

Because of this, I have been working closely with the module team to embed reverse learning design (prioristing the intended learning outcomes instead of topics to be covered) and informed pedagogy into the design and drafting, so that students are well supported throughout their learning journey. As inclusivity was at the forefront of the design process for Art and Life before 1800, I carried out some research on module design for neurodiverse students, particularly those with dyslexia. In this post, I will share with you the findings from this research and will leave you with some tips and techniques that you can use in your own practice methods.

People with dyslexia can find auditory processing of information difficult; active learning is a much better way to make learning accessible and inclusive. Research suggests that getting students to transform information into different formats aids in retention of information and processing (e.g., producing a visual diagram, a poster, or storyboard, etc) and this can be helpful particularly to students with dyslexia (although it benefits everyone).

Writing style

The British Dyslexia Association (2023a) has a useful style guide on their website; the principles in the guide help you consider the difficulties experienced by some dyslexic people and gives advice on how to use text and speech to facilitate ease of reading. When carrying out my research, I found the ‘Writing Style’ section to be the most useful in terms of module design. Here are the main points:

-

- Use active rather than passive voice.

- Be concise; avoid using long, dense paragraphs.

- Write in simple clear language using everyday words.

- Use images to support text. Flow charts are ideal for explaining procedures. Pictograms and graphics can help to locate and support information in the text.

- Consider using bullet points and numbering rather than continuous text.

- Give instructions clearly.

- Avoid double negatives.

- Avoid abbreviations where possible; always provide the expanded form when first used.

- Provide a glossary of abbreviations and jargon.

Dyslexia-friendly teaching

The British Dyslexia Association (2023b) also has a useful page on providing dyslexia-friendly teaching. Here are some points they suggest are helpful to consider:

-

- Dyslexic people tend to be big picture thinkers but may be less adept at processing and remembering detail. Give an overview of the [course/module] first and at the start of any new section of the [learning].

- Teach one thing at a time in bite-size chunks.

- Be prepared to demonstrate and give examples. Explanations may need to be expressed in more than one way if someone appears to have trouble grasping the point.

- Allow time for over-learning – practice, practice, practice.

- Get learners to visualise doing the task or demonstrate it; then get them to say what they are doing whilst doing it. This gives the memory more to latch on to, to embed learning.

- [Build-in] breaks during the learning process to help with concentration levels.

- Give a summary at the end of each learning point and an overview of the next session following the break. Check understanding of key points.

- Avoid using acronyms, metaphors, complex language, or phrases open to misinterpretation.

- Encourage an open culture where ideas can be shared.

Universal Design for Learning

The Universal Design for Learning Guidelines offer a set of concrete suggestions that can be applied to any discipline or domain to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities.

Engagement: For purposeful, motivated learners, stimulate interest and motivation for learning (CAST, 2018a).

Representation: For resourceful, knowledgeable learners, present information, and content in different ways (CAST, 2018b).

Action and expression: For strategic, goal-directed learners, differentiate the ways that students can express what they know (CAST, 2018c).

Communities of Practice

Recent research studies evidence that students’ higher levels of motivation and self-confidence, together with improved academic engagement and achievement, are linked to a greater sense of belonging (Pedler, Willis and Nieuwoudt, cited in Welton, 2023). This sense of belonging can be created through the development of a non-hierarchical community of practice, which aims to empower students to foreground and communicate their individuality, and as a result of this empowerment acts as a platform to help non-dyslexics understand different ways of thinking.

Additional help and support

Organisation and time management are two factors, which dyslexic students frequently struggle with, alongside their difficulties with reading and writing.

Taking notes is challenging for dyslexic students, as the level of concentration needed to write the notes, results in them missing the next few sentences of the lecture. Using a voice recorder allows the student to concentrate fully on a lecture, with the confidence that they can recap later using the recording. However, the recording will need some form of cataloguing after the lecture. For each lecture recorded the student will then need to spend as much time, if not more, listening back to the lecture, to highlight the important points, and produce a useful revision aid (Robson, 2014).

Call to action

If you’d like to talk with the Learning Design team at The Open University about any dyslexia or neurodiversity related design support you’d find useful for your organisation, whether that’s running a session for you, helping you to use some of the resources we’ve shared via this blog, or simply for a bit of advice, we would love to hear from you. Please contact us at: [email protected].

References

British Dyslexia Association (2023a) Dyslexia Friendly Style Guide [Online]. Available at https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/employers/creating-a-dyslexia-friendly-workplace/dyslexia-friendly-style-guide (Accessed 17/07/2024).

British Dyslexia Association (2023b) Dyslexia Friendly Training [Online]. Available at https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/employers/creating-a-dyslexia-friendly-workplace/dyslexia-friendly-training (Accessed 17/07/2024).

CAST (2018a) ‘Provide multiple means of engagement’, Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2 [Online]. Available at https://udlguidelines.cast.org/engagement/ (Accessed 17/07/2024).

CAST (2018b) ‘Provide multiple means of representation’, Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2 [Online]. Available at https://udlguidelines.cast.org/representation (Accessed 17/07/2024).

CAST (2018c) ‘Provide multiple means of action and expression’, Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2 [Online]. Available at https://udlguidelines.cast.org/action-expression (Accessed 17/07/2024).

Robson, L. (2014) ‘Additional help, additional problem – issues for supported dyslexic students’, HEA STEM Annual Conference, 30 April to 1 May, University of Edinburgh, Scotland [Online]. Available at https://oro.open.ac.uk/39781/3/39781.pdf (Accessed 17/07/2024).

Welton, K. (2023) ‘Dyslexia in higher education: enhancing student belonging and overcoming barriers to achievement through communities of practice’, Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, no. 26, February [Online]. Available at https://journal.aldinhe.ac.uk/index.php/jldhe/article/view/933/711 (Accessed 17/07/2024).

Banner image: via Canva / ixus142