We are delighted that Professor Martin Weller has been appointed as the new Chair of the Open Board of Studies in our 50th anniversary year!

We are delighted that Professor Martin Weller has been appointed as the new Chair of the Open Board of Studies in our 50th anniversary year!

Martin is Professor of Educational Technology with an interest in the application of new technology to academic practice, open education and digital scholarship. This post was originally published on Martin’s personal blog here.

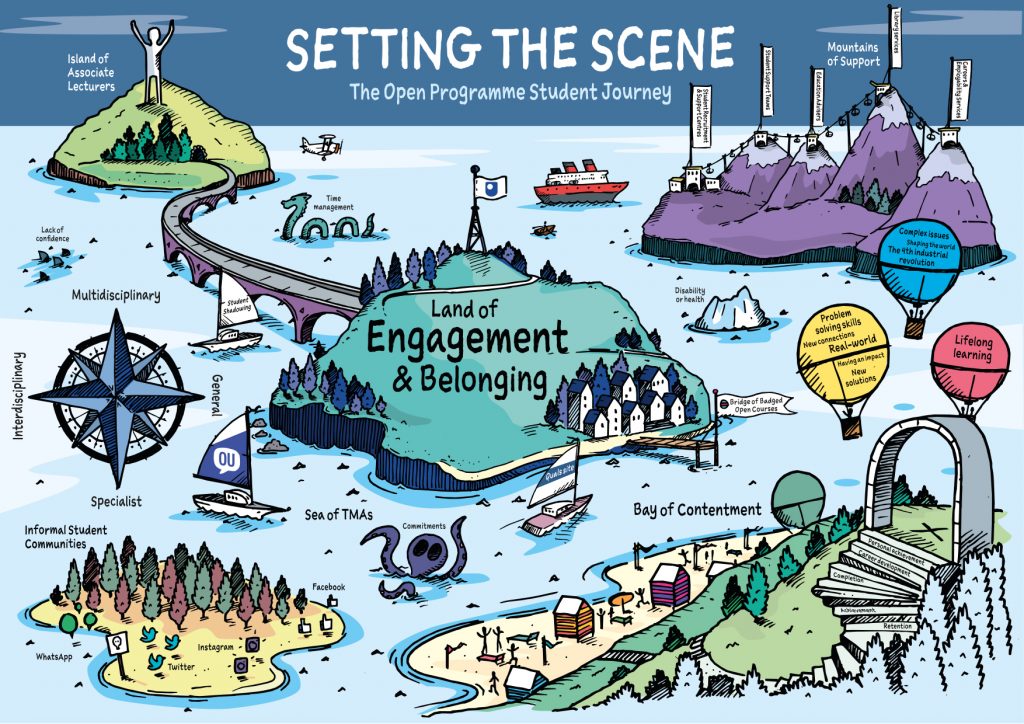

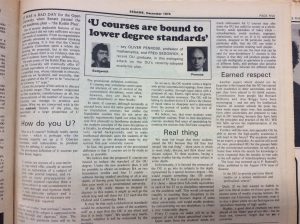

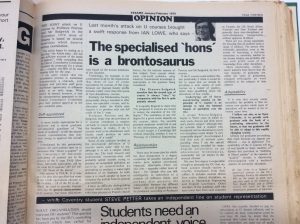

I’ve recently taken on a new role at the Open University, as the Chair of the Open Board of Studies. This means I’ve got responsibility for our Open Degree. When the OU was founded you could only get a BA(Open) – there were no named degrees. This was an explicit attempt by the OU’s founders to make an OU degree different not just in mode of study but in substance. Students constructed their own degree profiles, meaning our modules were truly modular, you could pick and mix as you saw fit. My colleagues Helen Cooke, Andy Lane and Peter Taylor give an excellent overview of the history, philosophy and approach of the open degree in this paper.

The OU’s first Vice-Chancellor put it like this:

![a student is the best judge of what [s]he wishes to learn and that [s]he should be given the maximum freedom of choice consistent with a coherent overall pattern. They hold that this is doubly true when one is dealing with adults who, after years of experience of life, ought to be in a better position to judge what precise studies they wish to undertake](https://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/openquals/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/D7kBenbX4AE-lrD-1024x576.jpg) Sure, most universities offer options and electives, but a truly flexible, open choice is very rare. Specialism is of course, a desirable mode of study in many areas. But the reasoning behind the original open choice was that the changes in society and work places in the 70s meant that a wide ranging degree was suitable for many vocations. If that was true at the founding of the OU, then it is doubly so now. While we should be sceptical of the “preparing students for jobs that don’t exist yet” claims, it’s fair to say that flexibility and breadth of understanding will be useful attributes in an evolving, digital economy. Let’s take my own area (field/discipline/rag tag bundle of vaguely connected ideas) of educational technology. You can create a degree programme that covers much of what you want, but actually it’s a varied domain, and half of the work involves having an understanding or appreciation of the demands of different subject areas. So a degree that has rich, and unpredictable, variety in it might well be exactly what you want for an educational technologist. And that is increasingly true for roles that evolve around tech, but are not necessarily TECH.

Sure, most universities offer options and electives, but a truly flexible, open choice is very rare. Specialism is of course, a desirable mode of study in many areas. But the reasoning behind the original open choice was that the changes in society and work places in the 70s meant that a wide ranging degree was suitable for many vocations. If that was true at the founding of the OU, then it is doubly so now. While we should be sceptical of the “preparing students for jobs that don’t exist yet” claims, it’s fair to say that flexibility and breadth of understanding will be useful attributes in an evolving, digital economy. Let’s take my own area (field/discipline/rag tag bundle of vaguely connected ideas) of educational technology. You can create a degree programme that covers much of what you want, but actually it’s a varied domain, and half of the work involves having an understanding or appreciation of the demands of different subject areas. So a degree that has rich, and unpredictable, variety in it might well be exactly what you want for an educational technologist. And that is increasingly true for roles that evolve around tech, but are not necessarily TECH.

It is often claimed that in order to solve the complex, ‘wicked’ problems that the world faces, such as sustainability, climate change, social inclusion, then interdisciplinary thinking is required. But our degree profiles continue to prioritise narrow specialisms instead of encouraging students to develop knowledge and skills across a range of topics. This gives them empathy with other viewpoints and a broader toolkit of conceptual models.

Perhaps more significantly than the employment argument though is that constructing your own degree profile and taking responsibility for your pathway gives agency to learners. George Veletsianos asks “in education, what can be made more flexible?”, to which I would respond the whole degree structure.

Coming to this from a broader open education perspective, I see the work of OER, open textbooks, open access and MOOCs as laying the necessary groundwork for a wave of more interesting exploration around what open approaches offer. Open pedagogy and Open educational practice are examples of this. I would argue that although it is already 50 years old, the truly open choice of the OU is another one and it’s time has come round again.

Rehana Awan is Student Communications and Engagement Manager in Curriculum Innovation, working primarily on designing and enhancing the student experience for Open Programme students and Associate Lecturer on the People, Work and Society Access module. Rehana is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (SFHEA) and Fellow of the Staff and Educational Development Association (FSEDA). This blog post originally appeared on Rehana’s personal blog available

Rehana Awan is Student Communications and Engagement Manager in Curriculum Innovation, working primarily on designing and enhancing the student experience for Open Programme students and Associate Lecturer on the People, Work and Society Access module. Rehana is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (SFHEA) and Fellow of the Staff and Educational Development Association (FSEDA). This blog post originally appeared on Rehana’s personal blog available

Professor Peter Taylor is the current Chair of the Open Board of Studies and Qualification Director for the BA/BSc (Hons) Open degree.

Professor Peter Taylor is the current Chair of the Open Board of Studies and Qualification Director for the BA/BSc (Hons) Open degree.

Jay Rixon is a Senior Manager in Curriculum Innovation and responsible for the new MA or MSc Open qualification.

Jay Rixon is a Senior Manager in Curriculum Innovation and responsible for the new MA or MSc Open qualification. In the

In the

Helen Cooke is a Senior Manager in Curriculum Innovation and responsible for the day-to-day running of the Open Programme. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (SFHEA) based on her work supporting multidisciplinary students in an online environment.

Helen Cooke is a Senior Manager in Curriculum Innovation and responsible for the day-to-day running of the Open Programme. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (SFHEA) based on her work supporting multidisciplinary students in an online environment. This happened to me last year when I stumbled across Emilie Wapnick’s fabulous book

This happened to me last year when I stumbled across Emilie Wapnick’s fabulous book