Professor Peter Taylor is the current Chair of the Open Board of Studies and Qualification Director for the BA/BSc (Hons) Open degree.

Professor Peter Taylor is the current Chair of the Open Board of Studies and Qualification Director for the BA/BSc (Hons) Open degree.

In July 1974, not long after my 21st birthday, the OU Senate agreed the “Kettle Plan” [1]. This was not a proposal to ensure that OU staff were never more than 20 metres from a means of boiling water but the equivalent of the OU’s current Curriculum Plan. Professor Arnold Kettle chaired the working group that put the proposals together and it provides a lens on the vision for the university in those early years.

Effectively, the Kettle Plan said that, based on the future size and resources of the OU, the number of ‘full credit equivalents’ (modules) produced by the university would be 87. However, you have to remember that the units are different here. A ‘full credit equivalent’ then was what we call a 60 credit module now. The fact that in 2017/18 there were 335 undergraduate modules and 119 postgraduate modules (a mix of half and full credit equivalents in old money) suggests we have long ago busted the plan set out in Professor Kettle’s report.

However, the important point is that the Kettle Plan promoted three types of course “that must have equal priority”:

a) Foundation courses

b) The more specialist or ‘intrinsic’ courses

c) The more general, broadly-based course… “that don’t necessarily fit conveniently within any one discipline or even Faculty”, known as ‘U’ courses.

In fact, it was proposed that about 22 full credit equivalents (say 11 60-credit modules and 22 30-credit modules in new money), about 25% of the University’s output, should be produced.

The Kettle Plan goes on to argue that:

“Between the relative educational merits of the latter two types of course there is, as in all universities, a good deal of disagreement within the OU. Some people (students and academics) are suspicious of the broader courses fearing they can turn out to be superficial. Others are equally convinced that most conventional university degree patterns are greatly over specialised and that the OU neither can nor should compete in attempting to provide the more specialist type of degree”.

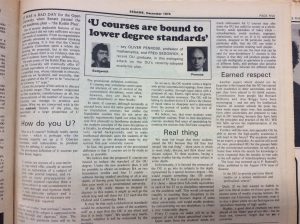

At the time, some argued that “U courses are bound to lower degree standards” [2] while others argued “the specialised ‘hons’ is a brontosaurus” [3].

Now, nearly 50 years later, there is little hint of broadly-based modules that “don’t necessarily fit conveniently within any one discipline or even Faculty” in the OU’s current curriculum portfolio. Our silo mentality, our inability to work out how to finance such modules and our need to defend and promote our disciplines has practically erased them from the face of the university.

Almost exactly 50 years ago, the Report of the Planning Committee to the Secretary of State for Education and Science stated:

“The degree of the Open University should, we consider, be a “general degree” in the sense that it would embrace studies over a range of subjects rather than be confined to a single narrow speciality.” [4]

Part of the driver for this was employability:

“Furthermore we are aware of the great need and demand in the country….for an extension of facilities for such general degrees… We have become accustomed to the idea that the career of an individual spans only one major technological phase: it is certain in the future that it will span two or even more such phases… The university will have an important role arising from the changes in, and increasing rate of change within modern technological society.” [4]

These employability messages don’t seem to have changed over 50 years and the Institute of Student Employers (2018) suggests that only 26% of employers focus on recruiting students from particular disciplinary backgrounds [5], yet over the years as a university we have still drifted down the path of specialisation.

Maybe we can’t buck market forces and so we have followed the crowd; but in doing so, we have lost a lot of our uniqueness and lost the vision of our Founding Fathers.

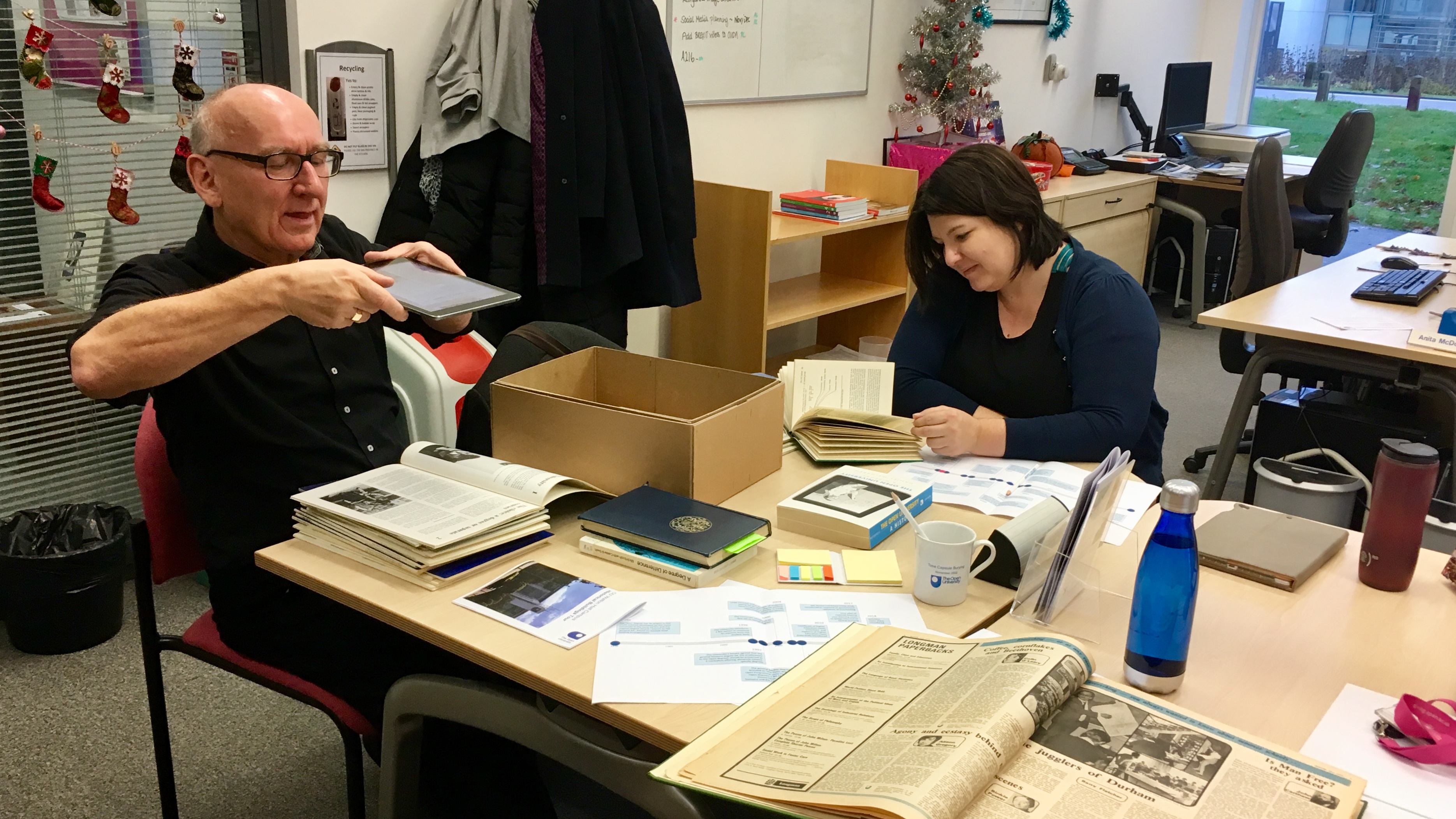

Jay Rixon is a Senior Manager in Curriculum Innovation and responsible for the new MA or MSc Open qualification.

Jay Rixon is a Senior Manager in Curriculum Innovation and responsible for the new MA or MSc Open qualification. In the

In the

Helen Cooke is a Senior Manager in Curriculum Innovation and responsible for the day-to-day running of the Open Programme. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (SFHEA) based on her work supporting multidisciplinary students in an online environment.

Helen Cooke is a Senior Manager in Curriculum Innovation and responsible for the day-to-day running of the Open Programme. She is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (SFHEA) based on her work supporting multidisciplinary students in an online environment. This happened to me last year when I stumbled across Emilie Wapnick’s fabulous book

This happened to me last year when I stumbled across Emilie Wapnick’s fabulous book