I’d like to start by echoing Josie’s welcome to everyone, thank you all for coming, some of you long distances, it really is good to celebrate 50 years of the Open Programme.

Because I’ve been here a long time, I’m often seen as a kind of ‘historian’ of the Open University and I believe that multidisciplinary study at the Open University had its foundations in this 1968 document. So, it’s the “Flow into employment of scientists, engineers and technologists” and it was the Committee on Manpower Resources for Science and Technology. Now, you have to remember that this was Harold Wilson’s ‘White Heat of Technology’, so it was all about technology, but all about the Open Programme as well:

[Audio recording] “We have become accustomed to the idea that the career of an individual spans only one major technological phase. It is almost certain in the future that it will span two or even more phases. To meet current and future needs of employment and to give students of science, engineering and technology some understanding of the society in which they work, universities should consider making the first degree course in science, engineering and technology broad in character, through multidisciplinary approaches to these subjects and by introducing relevant study in other field such as economics, sociology, law etc.”.

Plus ça change [laughter]… that really could’ve been written last week, and is as relevant 50 years ago as it is today. The report was actually chaired by Michael Swan, who was Vice Chancellor of Edinburgh and went on to be Chairman of the Governors of the BBC, hence it was called the Swan Report. That was [19]68 and, at the same time, the Open University was being planned and I believe this document had a big influence on the planning of the Open University. So here we have the 1969 Report of the Planning Committee to the Secretary of State, Education on Science for the Open University:

[Audio recording] “Besides providing fresh and renewed opportunities for such students as we have been discussing, the University will have an important role arising from the changes in, and increasing rate of change, with a modern technological society. The degree of the Open University should, we consider, be a general degree, in the sense that it would embrace studies over a range of subjects, rather than be confined to a single narrow speciality. In our view the OU should not set out to compete with the established universities which can spend 3 years of full-time study in their laboratories and libraries and their specialised school. Rather should the Open University degree be complementary, providing the part time student a broadly-based higher education for which the teaching techniques available to the Open University are particularly suited. Furthermore, we are aware of the great need and demand in the country, emphasised in the Swan Report, for an extension of facilities, such as general degrees”.

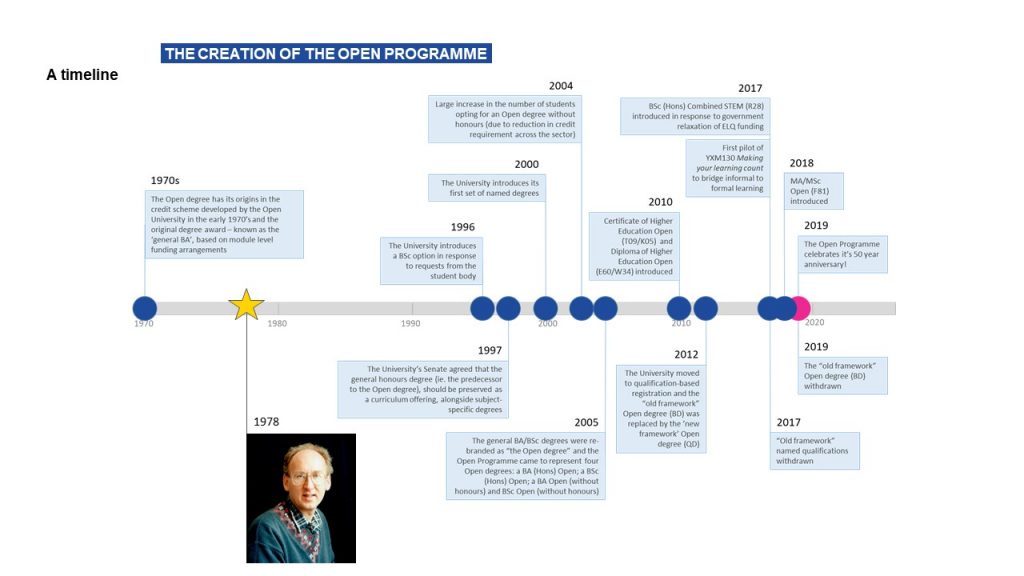

So, the Open University had multidisciplinary study at its heart. The BA was introduced in 1970 and was pretty much the only degree until 1996 when the BSc was introduced. The nature of this multidisciplinary degree was nicely described by our first Vice-Chancellor Walter Perry in his book about the development of the Open University and you have probably heard me quote this many times: –

[Audio recording] “The usual criticism is that a student has a free choice of courses that he can take credit for is liable to end up with what is called a miscellaneous ragbag of credits, a second-rate degree with no internal coherence. Such people argue strongly that teachers must determine the pattern of studies that is most suited to the individual and that direction of this kind is the essence of education. Opponents of this view on the other hand argue equally strongly that a student is the best judge of what he wishes to learn and that he should be given the maximum freedom of choice, consistent with a coherent overall pattern. They hold that this is doubly true when one is dealing with adults who, after years of experience of life, ought to be in a better position to judge what precise studies they wish to undertake”.

So, in the early days, it was recognised that our students, particularly as adults, are not blank canvases on which we paint. They bring with them a multitude of skills and knowledge from their life, from their interests, from their work, and they want to do modules that reinforce and help develop those areas to help them meet their goals. These students are brave students, not for them the well-trodden path of a named degree, they plough their own furrow. When I first started as Director of the Open Programme, I was convinced that if I looked hard enough, I’d be able to find certain common pathways that Open Programme students took. I was quickly dissuaded of that fact in that every single student seemed to take a completely different set of modules; it was about what they needed, what were their hopes, and their intentions. Every student therefore is unique, and we should really celebrate that variety.

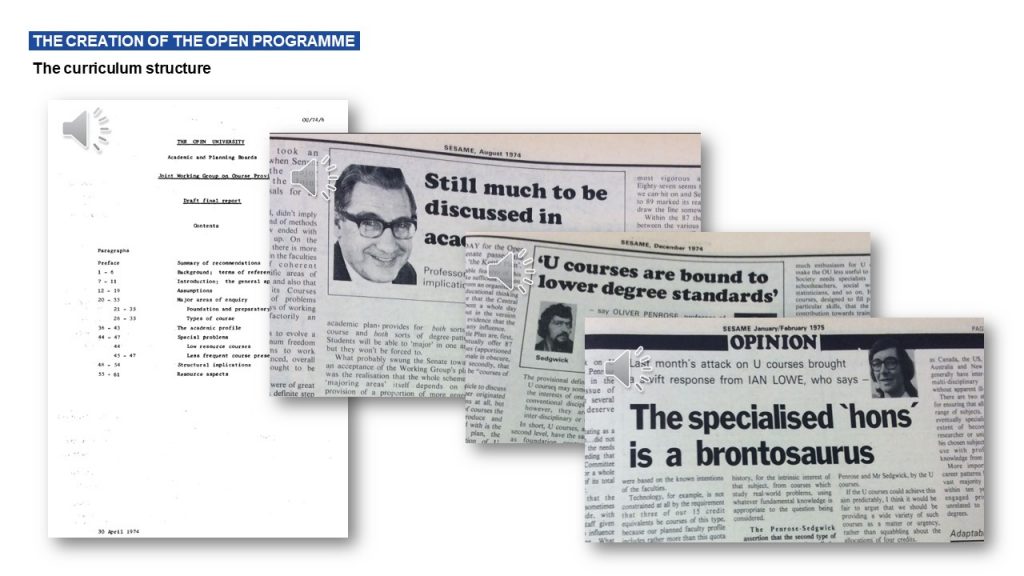

So much for the way the degree is set up, let’s look at the way the curriculum was developed in those early days and, for this, I have a report from 1974, which is the Joint Working Group on Course Provision, that was chaired by Professor Arnold Kettle [hereafter referred to as ‘the Kettle Report’].

One of the main recommendations was that, as well as having specialist modules, we ought to have interdisciplinary modules and he called those ‘intrinsic courses’ for specialist and ‘less intrinsic’ for multidisciplinary: –

[Audio recording] “Within a University there should be room for a diversity of approaches, nevertheless we believe that it is important that the University should face the need to produce a larger proportion of the more general, less intrinsic type of course. It is a key part of the Joint Working Group’s recommendation that the University should produce a larger number of more general broadly-based courses with minimal prerequisites”.

The student newspaper at that time was something called Sesame and [Professor Kettle] went on to say in Sesame a little bit more, not only about the need for general modules, but some of the challenges in implementing them: –

“Between the relative educational merits of the latter two types of course, there is, as in all universities, a great deal of disagreement within the OU. Some people, students and academics, are suspicious of the broader courses, fearing that they can turn out to be superficial. Others are equally convinced that most conventional university degree patterns are greatly overspecialised and that the OU neither can, nor should, compete in attempting to provide the more specialist type of degree”.

These courses became known as University courses, or U courses, so things like U201 (risk), U202 (enquiry), U203 (popular culture) and the Kettle Report suggested that as much as 25% of our modules should be interdisciplinary. As predicted, there was a lot of discussion about whether we should have more specialist or more interdisciplinary courses, as this particular article in Sesame suggests: –

“We believe that the proposed U courses are bound to reduce the standard of the OU degree. If the OU really means to cheapen it’s degrees to this extent, it might as well go the whole hog and sell them for £12 each, like the Oxford and Cambridge MA”.

But luckily there are other people who thought differently about the value of multidisciplinarity and, maybe, that named degrees were something of the past: –

“It is true that our society needs specialists, the problem is that we cannot predict which types of specialists will be needed in 10- or 20-years’ time. I believe our aim as an Open University is to provide each graduate with the basis of a continuing education in the future, so that our graduates will be able to adapt to this rapidly changing society. Already our graduates are making their mark because our degrees are different”.

As in many universities that have strong disciplinary silos, the ability to sustain interdisciplinarity is often a challenge. In particular, I think the way that we do our costing and income models for the Open University has led to a decline of this interdisciplinarity. Certainly, the U courses slowly disappeared and I’m not sure there are very many left at the moment.

But one last slide to talk about how we got to where we are today. Here we have our timeline – in 1970, the introduction of the BA, and in 1996, the introduction of the BSc. And somewhere between the two, there’s this fresh-faced lad who started in 1978, full of hopes and ambitions, and look where it got him! [laughter]

In the year 2000, we introduced named degrees, but even though students often wanted to do named degrees, still 25% of our students wanted to study in a multidisciplinary fashion. Since then, we’ve had things like certificates and diplomas, we’ve had the whole move from the old framework to the new framework, but more recently we’ve introduced things like the Open Masters, the STEM version of the Open Programme and our first module on ‘Making your learning count’.

So, we’ve come a long way in 50 years. I’m hoping we’re still flying that flag of multidisciplinarity. As Helen said, I will be giving up the flag and passing it on to others at the end of July, but I’m sure the university will continue in that interdisciplinary fashion and value it.

Looking forward to the future, I am looking forward to completing challenging, but rewarding modules in statistics, before progressing to my final module, Issues in research with children and young people. I intend to graduate with a 2:1 or above in a degree that is both highly specialised to my current career path and highly flexible to suit many other areas (should I need to change in the future), having developed both in-depth academic knowledge in my chosen area and core aptitudes valued by employers

Looking forward to the future, I am looking forward to completing challenging, but rewarding modules in statistics, before progressing to my final module, Issues in research with children and young people. I intend to graduate with a 2:1 or above in a degree that is both highly specialised to my current career path and highly flexible to suit many other areas (should I need to change in the future), having developed both in-depth academic knowledge in my chosen area and core aptitudes valued by employers