Philippa Costello is an Ambitious Futures Graduate Trainee, currently working within the Curriculum Innovation Team. She is currently studying towards a Certificate of Higher Education in Economics and Personal Finance with The Open University.

The Institute of Student Employers (ISE) is a member organisation that works to represent over 150 ‘student employers’ or ‘graduate recruiters’. They work with both employers and universities to provide support in all aspects of student recruitment.

This year, their HE conference was based around the topic of ‘What Employers Want’.

So, as someone who does not directly work as a Careers Advisor or within Employer Outreach, you may be wondering why I opted to make the trip to the London Business School (lovely catering FYI) on very cold November morning…

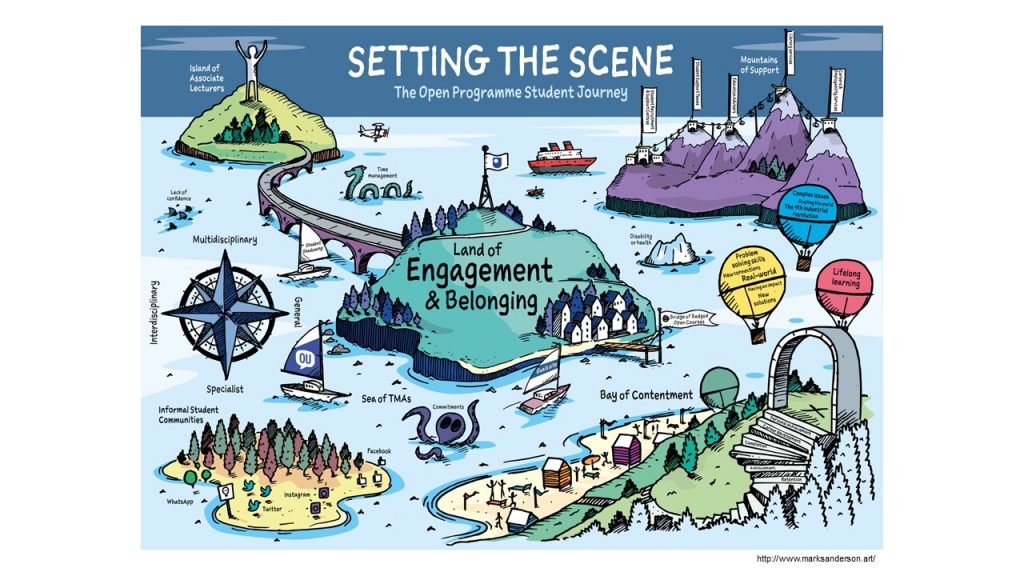

Well, the team who manages ‘Open’ qualifications (that includes all of the ‘Open’ qualifications, the BSc (Hons) Combined STEM degree, and the MA/MSc Open!) have been interested for some time about how we best equip students with the vocabulary to communicate to their existing or potential employers what their ‘Open’ qualification is. Most importantly, we need employers to understand why obtaining a multidisciplinary qualification – be your module choices be based on personal interest or a desire to up-skill or increase your employability prospects – is valuable in our current labour market.

Source: @IoSEorg

Dr Charlie Bell is Head of Higher Education Intelligence at Graduate Prospects, a UK sector agency which supports university careers services (and other interested parties) by providing universities with up-to-date research data on graduate issues, amongst other things.

Bell presented his research findings through dispelling myths, which was refreshing in a world of ‘fake news’ (or at least questionable news!). We’ve all heard them; ‘Everyone has a degree nowadays’, ‘All the jobs are in London’, and ‘You’ll have to go into a job that’s linked to what you’ve studied’.

However, research shows only 39.2% of the adult population (16-64 years) had a degree by the end of 2018, and of the workforce, this number still came in at under 50%. Bell prophesied that this may well get to 50% (of the workforce), at which point the narrative around ‘graduate premium’ may shift and become a ‘penalty’ for those who cannot or don’t want to obtain a higher-level qualification.

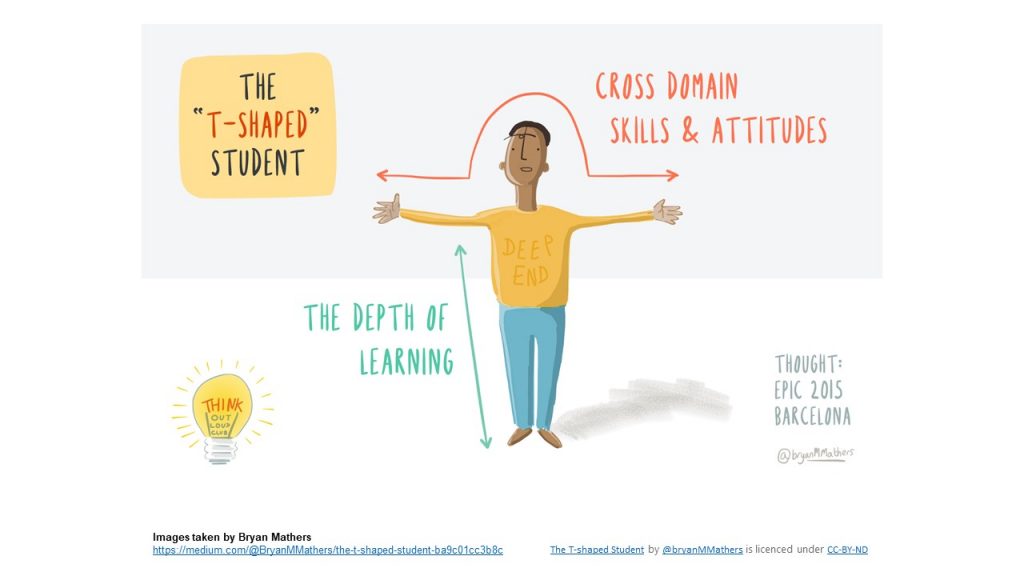

Bell also addressed the myth that ‘subject studied equals vocation’ (it doesn’t!), and of course, the most promising statistic of the talk was that 60-70% of employers are ‘degree blind’. That is, employers generally aren’t all that concerned with the subject(s) you have studied in non-vocational or very ‘general, broad roles’.

“The UK has a particularly flexible skilled jobs market…Degrees are designed to teach a wide range of skills as well as subject knowledge and employers understand that.”

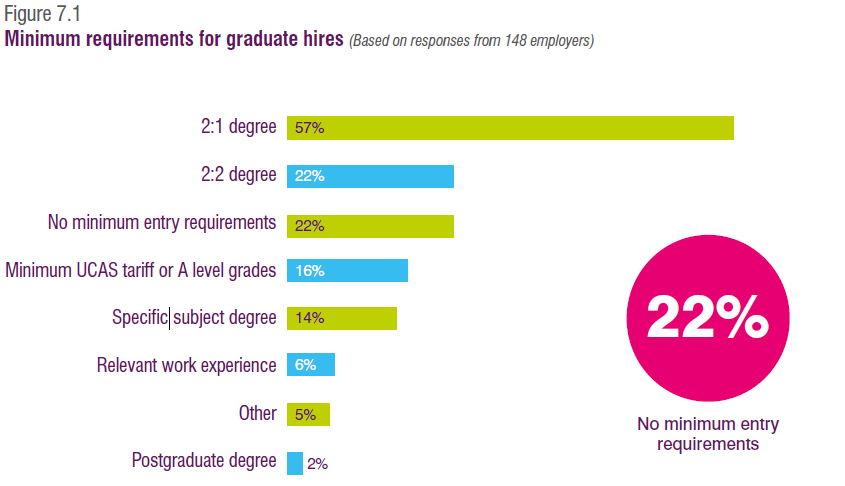

The latest Institute of Student Employers student recruitment survey (2019) shows that only 14% of the employers who responded said that a specific subject degree forms part of their minimum requirement for graduate hires, and 22% state that they have no minimum entry requirements whatsoever.

Source: ‘Inside student recruitment 2019’, Institute of Student Employers

So, what does this mean for supporting students studying multidisciplinary qualifications at the OU?

To help Open qualification students to feel confident in their interactions with employers, we have a range of resources* that students can access to help them identify the transferable skills they have gained as a result of studying across disciplines and to effectively communicate the variety and quality of what they have studied. We’ve also put together some useful information around Open degree module combinations and offered suggested career pathways.

The Careers and Employability Services also provides some valuable resources to help plan your career.

Don’t forget, if you’re a current student or former student who’s finished your studies within the last three years, you can request a one-to-one careers consultation!

*OU login required