It’s International Yoga Day! Over at the Ayuryog blog, the Open University’s Suzanne Newcombe writes about the revival of yoga in contemporary India.

It’s International Yoga Day! Over at the Ayuryog blog, the Open University’s Suzanne Newcombe writes about the revival of yoga in contemporary India.

Marion Bowman, John Maiden and Paul-Francois Tremlett recently appeared on the Arts and Social Science Showcase at the Student Hub to present the new course, Exploring Religion (A227). The module challenges various widely held assumptions about religions and the study of religion, and engages students with three core questions: What is religion? How do we study religion? Why should we study religion?

David Robertson recently chaired a roundtable discussion entitled Millennialism and Violence? with Eileen Barker, Moojan Momen, Joseph Webster and Tristan Sturm, at the CenSAMM conference at the Panacea Trust in Bedford:

Descriptions of the End Times are full of violent imagery, of mass destruction through earthquakes, tidal waves, fire and ice. These images are written deeply into our culture through the book of Revelation, but are by no means limited to the Christian imagination. Often, our idea of modern millennial groups is informed by images of violent confrontations between them and the state, for example at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, or of mass suicide, such as with Heaven’s Gate or the People’s Temple at Jonestown.

Are we right to connect millennialism and violence? Are these groups typical, or rare exceptions, magnified out of proportion by the lens of the media – and scholarship? How do we account for the popularity ofmillennialismm outside of religious traditions, new, extreme or otherwise?

You can find an audio version and a full transcript over at the Religious Studies Project. The episode was produced in collaboration with CenSAMM, the Centre for the Study of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements.

By Suzanne Newcombe

Academics often talk about the importance of scholarly dialogue. More often than not we talk with our colleagues through writing, with large gaps of time and space. Therefore, it was a breath of fresh air to be able to participate in Knut Jacobson and Ferdinando Sardella’s initiative on Hinduism in Europe (http://www.erg.su.se/english/hinduism-in-europe/hinduism-in-europe-introduction-1.326684). This ambitious project will eventually result in a comprehensive edited volume published by Brill, with thematic chapters as well as country profiles covering ‘Hinduism’ in Europe.

‘Hinduism’ is widely acknowledged to be a problematic term. The conference included self-conscious discussions of the creation of Indology and the academic study of Hinduism. This is something that was grappled with differently in each national context, though patterns and international exchanges are also central to understanding how Hinduism has been defined and understood.

‘Hinduism’ is widely acknowledged to be a problematic term. The conference included self-conscious discussions of the creation of Indology and the academic study of Hinduism. This is something that was grappled with differently in each national context, though patterns and international exchanges are also central to understanding how Hinduism has been defined and understood.

In many northern European post-soviet states, there are still no substantial groups of Indian migrants. Until recently in this context, Hinduism was only represented by academic study and in esoteric religiosity. After 1989, a number new transnational groups have established a presence most of these areas, the most common being ISKCON, Sahaja Yoga, Transcendental Mediation and the Art of Living Foundation.

Yet even amongst the Eastern European states, experiences of Hinduism have varied considerably. ISKCON has found particular success in the Ukraine. In Bulgaria, there is a long history of yoga as sport in Adult Education. Various Romanian individuals have consistently turning towards India for inspiration despite considerable practical and political pressures. The contributions on Hinduism in Russia and Turkey were especially valuable for bridging the mixed experiences in the geographically continuous – but culturally and religiously diverse – territory bridging Europe and Asia.

Yet even amongst the Eastern European states, experiences of Hinduism have varied considerably. ISKCON has found particular success in the Ukraine. In Bulgaria, there is a long history of yoga as sport in Adult Education. Various Romanian individuals have consistently turning towards India for inspiration despite considerable practical and political pressures. The contributions on Hinduism in Russia and Turkey were especially valuable for bridging the mixed experiences in the geographically continuous – but culturally and religiously diverse – territory bridging Europe and Asia.

In some countries, specific colonial histories have created immigrant groups whose voices dominate national discussions on Hinduism. In Britain, the well-organized voices of BAPS Swaminarayan and ISKCON dominate national debates on Hinduism. This often partially silences the more inward-facing communities of Tamil refugees who fled Sri Lanka’s Civil War. It is this Tamil-refugee population that forms the majority of Indian groups in France and Germany.

In contrast, Hinduism in The Netherlands is more defined by its particular colonial legacy of Indian immigrants from Suriname, originally indentured labourers from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. In all national contexts, we heard about the negotiations between specific groups and the legal and cultural restrictions on building public temples, or holding large public events.

I was asked to contribute on the subject of ‘Yoga in Europe’, which I know mostly from a British context and English-language based research. Therefore, it was refreshing to have input from such a variety of political, cultural and linguistic contexts. Other thematic contributions also enriched my understanding, notably papers elucidating the esoteric and Ayurvedic narratives across Europe.

I was asked to contribute on the subject of ‘Yoga in Europe’, which I know mostly from a British context and English-language based research. Therefore, it was refreshing to have input from such a variety of political, cultural and linguistic contexts. Other thematic contributions also enriched my understanding, notably papers elucidating the esoteric and Ayurvedic narratives across Europe.

I left enriched, beginning a process of re-evaluating my understandings. I now have a greater appreciation of distinct transnational flows and specific migration patterns; I have more knowledge of local histories, the diversity of related linguistic and conceptual categories and country-specific political pressures.

This conference was a model in the importance of considering contemporary religion in historical – and comparative – perspective.

Theo Wildcroft, PhD Candidate

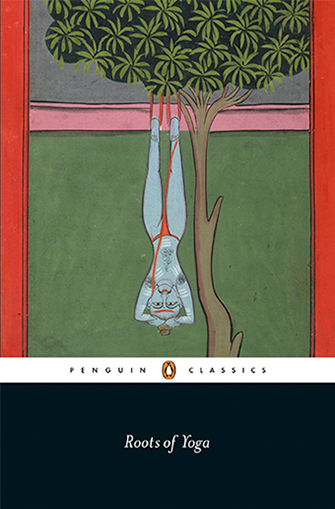

Roots of Yoga, authored by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, is the first major text from one of the most significant research projects into the history of hatha yoga, the familiar form based on postures. As such, the book has been eagerly awaited by scholars and practitioners alike. Whilst contemporary yoga has become globally popular through the last century or more, the source material for that globalisation is surprisingly narrow.

Roots of Yoga, authored by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, is the first major text from one of the most significant research projects into the history of hatha yoga, the familiar form based on postures. As such, the book has been eagerly awaited by scholars and practitioners alike. Whilst contemporary yoga has become globally popular through the last century or more, the source material for that globalisation is surprisingly narrow.

Roots of Yoga aims to bring to light more of the vast diversity of pre-modern hatha yoga practice. It collates curated extracts from original pre-modern texts, together with an analysis of common themes and differences. It also acknowledges non-Indian and non-Hindu influences that are mostly omitted from non-academic accounts of hatha yoga. This bold choice will have political as well as scholarly implications.

The reception of historical yoga scholarship beyond the academy can be fraught. The narrow source material of most contemporary yoga was reformed in the pre-independence period, invigorated with transnational influences, combined with medical terminology and neo-Vedantic philosophy, and promoted as an enduring, ancient, authentically Indian practice for holistic health. That practice eventually proliferated into global significance, still trading on associations with authentic Indian roots, but increasingly subject to commercial appropriation. One overt aim in recent years for both American activists for social justice and the right-wing Hindu nationalist Indian government is to ‘return’ yoga to control by its perceived culture of origin. This has become entangled with politics of caste and sect, and denies the long history of multi-faith syncretism shown by Roots of Yoga, as well as a century of transnational innovation within the evolution of yoga. As such, the reception of new historical commentaries on yoga has become highly politicised.

Few would wish to repeat the experience of Wendy Doniger, whose The Hindus was removed from sale in India following governmental pressure. But as a researcher of contemporary, rather than historical practice, I find that it is in social media spaces that the impact of new scholarship is first felt beyond the academy. Mark Singleton’s previous book, Yoga Body, had a powerful impact on the transnational yoga scene. Followers of the Mysore lineages have understandably been the most resistant, whilst secular reformers and post-lineage innovators alike find in the book a strong justification for their own evolution of the practice.

The most common dismissal of Mark’s work, and that of other academics, is that mere scholars as non-practitioners can only have the most superficial of understandings of the practice. Although Mark is a yoga practitioner, his co-author James Mallinson is much more demonstrably so, having appeared in a BBC documentary on the Kumbh Mela being ordained as a mahant. With copies of Roots of Yoga in just a few practitioner hands so far, it has already become common to respond to critics dismissing the book with a link to the BBC documentary.

Already, Roots of Yoga has both fervent supporters and critics who refuse to read it, organising along lines of sect and politics. So far, the most interesting review is that by the yoga writer and thinker Matthew Remski, for Yoga Journal. It perfectly encapsulates many of the contradictory forces currently acting upon transnational yoga culture.

The review’s title is “10 Things We Didn’t Know About Yoga Until This New Must-Read Dropped”, a click-bait title that makes its writer uncomfortable. Within the very short word limit, Matthew does his best to drop a number of key facts, focusing on core concerns of contemporary practice: the historical place of women in yoga, cultural diversity and appropriation, physical and emotional safety, body image and the clash between scientific and pre-modern epistemologies. Yoga Journal chose to accompany the article with links to less serious links such as ‘A Beginner’s Guide to the Chakras’, as well as exactly the kind of images of normative bodies that yoga cultural commentators like Matthew criticise in their writing. It leads to the delightful incongruity of number 8: “’Yogic suicide’ is a thing” illustrated by a woman sunbathing in a bikini. It’s an image that could be screenshot and used in any lecture on contemporary transnational yoga culture.

As Susan Palmer argued in her opening keynote at the CenSAMM conference on Millenarianism and Violence in Bedford last week, children are often the focus of particular attention within millenarian groups. As Mary Douglas argued, this is because the child is conceived of as the embodiment of the group’s ideals. The child is conceived of as both (simultaneously) perfect, and a blank slate, onto which the group may write their values.

Millennial ideas – and prophecy more generally – do not entirely concern the future, but rather the potentialities contained in the present. Concerns over the present order are critiqued using an idealised past, and projected into the future. Thus the prophetic present represents the potential of a better world, through the work of the group in question. The child therefore literally embodies that potentiality.

But we could invert the argument: if children represent the possibility of the community, is this the reason that children are so often at the centre of public and governmental concerns about New Religious Movements? Indeed , can we see the child as at the site of competition between the state and the NRM – who will inscribe their values more successfully?

As Palmer herself argued in her 2010 book The Nuwaubian Nation, charges of child abuse are a recurrent feature of accusations against minority religions. This can be seen in the histories of the The Children of God, Jim Jones’ People’s Temple, Branch Davidians, Lord Our Righteousness Church, MOVE among many, many others. We can also see it perhaps in the contemporary resurgence of media interest in Scientology, following the release of Going Clear, with contemporary concerns including the welfare of children (and Hubbard’s own children) increasingly at the centre of criticisms. Indeed, as I argued in my own paper at the conference, there is a millennial (and/or apocalyptic) subtext to paedophilia scares from the Satanic Ritual Abuse scare of the early 1990s to the very recent PizzaGate conspiracy narrative.

For each side, allowing the other side to instil their values into the child is tantamount to doing violence to them. Therefore, it can in some cases become permissible, even necessary, to commit violence to prevent this. This might well illustrate the claim by Stuart Wright later in the conference that violence is by no means an inevitable outcome of millenarianism, nor the result of some essential quality or attribute. Rather it is one possible result of the relationship between the groups and other groups, particularly legal or military, which represent the official state. Until the 1980s, the anti-cult movement relied predominantly on charges of brainwashing to encourage state intervention in NRMs. A brainwashed individual was essentially one stripped of agency and free will. The concept derived from the USA’s Asian wars of the 1950s to ‘70s, to explain why some GIs would defect to the other side. Few psychologists accept the existence of brainwashing today, however, so perhaps this is why the charges against NRMs increasing concern children.

For each side, allowing the other side to instil their values into the child is tantamount to doing violence to them. Therefore, it can in some cases become permissible, even necessary, to commit violence to prevent this. This might well illustrate the claim by Stuart Wright later in the conference that violence is by no means an inevitable outcome of millenarianism, nor the result of some essential quality or attribute. Rather it is one possible result of the relationship between the groups and other groups, particularly legal or military, which represent the official state. Until the 1980s, the anti-cult movement relied predominantly on charges of brainwashing to encourage state intervention in NRMs. A brainwashed individual was essentially one stripped of agency and free will. The concept derived from the USA’s Asian wars of the 1950s to ‘70s, to explain why some GIs would defect to the other side. Few psychologists accept the existence of brainwashing today, however, so perhaps this is why the charges against NRMs increasing concern children.

We might also note how often children are used by the state to legitimise violence against others. Only last week, Donald Trump justified missile strikes on Syria by stating that “Even beautiful babies were cruelly murdered in this very barbaric attack. No child of God should ever suffer such horror.” As ever, contemporary religions offer a microcosm of broader concerns and trajectories in culture – one more reason why Religious Studies is so vital today.

A full report on the conference will be published in the BASR Bulletin in May.

By Professor Graham Harvey

On 21 March 1617 a 22 year old woman, Lady Rebecca Rolfe, previously known as Pocahontas, was buried in St George’s church in Gravesend. On the 400th anniversary, 21 March 2017, a procession and church service commemorated her death and celebrated her alleged legacy. I was there as a scholar interested in observing the varied representations of Indigenous peoples and also their relationships with colonialism. Pocahontas / Rebecca Rolfe, provides a fascinating case study.

On 21 March 1617 a 22 year old woman, Lady Rebecca Rolfe, previously known as Pocahontas, was buried in St George’s church in Gravesend. On the 400th anniversary, 21 March 2017, a procession and church service commemorated her death and celebrated her alleged legacy. I was there as a scholar interested in observing the varied representations of Indigenous peoples and also their relationships with colonialism. Pocahontas / Rebecca Rolfe, provides a fascinating case study.

During the memorial procession and church service in Gravesend, no-one appeared to be dressed up as a little Princess Pocahontas. Groups of school children participated in the procession from a park beside the river Thames to the “Pocahontas Gardens” surrounding St George’s church. Many carried banners in the shape of feathers, but none of them wore feathers. The only feathered costumes in evidence were the one on the statue of Pocahontas in the church gardens and those worn by representatives of several Virginia Indian tribes who offered greetings during the church service. Visually, Pocahontas as romantic Indian was less in evidence than images of Lady Rolfe as aristocrat.

During the memorial procession and church service in Gravesend, no-one appeared to be dressed up as a little Princess Pocahontas. Groups of school children participated in the procession from a park beside the river Thames to the “Pocahontas Gardens” surrounding St George’s church. Many carried banners in the shape of feathers, but none of them wore feathers. The only feathered costumes in evidence were the one on the statue of Pocahontas in the church gardens and those worn by representatives of several Virginia Indian tribes who offered greetings during the church service. Visually, Pocahontas as romantic Indian was less in evidence than images of Lady Rolfe as aristocrat.

In speeches during the procession through the town and during the church service, Pocahontas was regularly called “Princess”, presumably because she was daughter of the Paramount Chief of the Powhatan Confederacy. Less often she was called “Lady Rolfe” or “Rebecca Rolfe”, recognising her status as wife of an aristocratic colonist and member of the Court of King James. She was represented as a loving Christian wife and mother, as an exemplar of Christian faith and as a peace-maker. She was celebrated as the “first fruits of Virginian conversion”, one who demonstrated the success of what Christians claimed was the civilising mission of colonialism.

In speeches during the procession through the town and during the church service, Pocahontas was regularly called “Princess”, presumably because she was daughter of the Paramount Chief of the Powhatan Confederacy. Less often she was called “Lady Rolfe” or “Rebecca Rolfe”, recognising her status as wife of an aristocratic colonist and member of the Court of King James. She was represented as a loving Christian wife and mother, as an exemplar of Christian faith and as a peace-maker. She was celebrated as the “first fruits of Virginian conversion”, one who demonstrated the success of what Christians claimed was the civilising mission of colonialism.

The dominant theme of the commemoration was that Pocahontas provides an example of a peace-making and reconciliation both during her life and down the centuries. It was never made clear how she did this in her lifetime. Possibly this was an allusion to her alleged saving of Captain Smith’s life or to her use as a hostage by Captain Argall in order gain the release of English settlers. Two other relationships were emphasised throughout the day. The first of these was between England and Virginia (and sometimes between the UK and USA). The procession was led by bearers of the flags of the UK and USA, and continuously referred to guests from the State of Virginia. The second emphasised relationship was between Christianity and colonialism. Although the Bishop of Rochester’s sermon briefly noted the “difficulty for some” of talking about colonialism, the 400th anniversary of the death of Pocahontas was largely a celebration of an English colony. At a time when many North American Christian denominations are announcing their rejection of the Doctrine of Christian Discovery (the foundational European justification for invasion and dispossession), it was unsettling to witness a ceremony in which even the representatives of Indigenous tribes celebrated the Virginia colonies as divinely mandated expansions of peace.

The dominant theme of the commemoration was that Pocahontas provides an example of a peace-making and reconciliation both during her life and down the centuries. It was never made clear how she did this in her lifetime. Possibly this was an allusion to her alleged saving of Captain Smith’s life or to her use as a hostage by Captain Argall in order gain the release of English settlers. Two other relationships were emphasised throughout the day. The first of these was between England and Virginia (and sometimes between the UK and USA). The procession was led by bearers of the flags of the UK and USA, and continuously referred to guests from the State of Virginia. The second emphasised relationship was between Christianity and colonialism. Although the Bishop of Rochester’s sermon briefly noted the “difficulty for some” of talking about colonialism, the 400th anniversary of the death of Pocahontas was largely a celebration of an English colony. At a time when many North American Christian denominations are announcing their rejection of the Doctrine of Christian Discovery (the foundational European justification for invasion and dispossession), it was unsettling to witness a ceremony in which even the representatives of Indigenous tribes celebrated the Virginia colonies as divinely mandated expansions of peace.

Much of this is summed up in one curious juxtaposition in the Pocahontas Gardens: a young man (not one of the Chiefs) sang out the names of Virginia’s Indigenous nations while standing next to the school girls who had sung the national anthems of the UK and USA at the beginning of the procession. Whoever Pocahontas was in life, remembrance of her appears to be deeply confused.

Much of this is summed up in one curious juxtaposition in the Pocahontas Gardens: a young man (not one of the Chiefs) sang out the names of Virginia’s Indigenous nations while standing next to the school girls who had sung the national anthems of the UK and USA at the beginning of the procession. Whoever Pocahontas was in life, remembrance of her appears to be deeply confused.

By Aled Thomas, PhD Candidate

The history of Scientology is peppered with conflicts between the Church of Scientology and its highly vocal critics. As ever, media depictions of the Church of Scientology (ranging from satirical lampoons to exposé documentaries) continue to be the main cause of Scientology’s woes in the public domain. Several documentaries on the activities of the Church of Scientology have been released in recent years, perhaps most notably Alex Gibney’s Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief in 2015.

The latest Scientology documentary to grab headlines is My Scientology Movie, featuring British documentary maker Louis Theroux. The Church of Scientology declined to take part in the documentary, and (according to Theroux) are in the process of making a response documentary based on him. Yet, frequent critics of the Church of Scientology may be surprised to learn of their recent shift towards a more reserved method of responding to critics, in a contrast to the fierce legal lawsuits with which the Church is often associated. As Lewis and Hellesøy (2016) note, the 2005 episode of South Park, ‘Trapped in the Closet’, (which famously ended with lead character Stan Marsh yelling “I’m not scared of you – sue me!”) marks an interesting point in the history of the Church, precisely because of the lack of lawsuit that followed the episode’s release. This is arguably the beginning of the Church of Scientology’s shift to its latest method of countering criticism: seeking status as a legitimate religion, and condemning its opponents for religious discrimination.

The release of Theroux’s documentary coincided with the Church of Scientology’s push of campaigns to secure its status as a religion. The first is STAND (Scientologists Taking Action Against Discrimination), a campaign “founded to put a stop to incitement of bigotry and hate crime, and to secure Religious Freedom for Man”. While STAND’s prime activities concentrate on protecting the Scientology religion (including reporting the hate crimes and dispelling myths regarding Scientology), it also aims to battle all forms of religious intolerance, linking back to Scientology’s emphasis on the human right to religious freedom. This demonstration of discrimination against Scientologists as being equally condemnable as any other form of religious discrimination points to the Church’s latest focus of combating critics by rebutting their accusations as religious bigotry, and portraying Scientology as an equally legitimate religion as more established movements.

It is this battle for its status as a ‘religion’ that leads to the Church of Scientology’s second recent campaign for religious legitimacy, its scientologyreligion.org website, for which the Church has turned to the expertise of the academic community. The website, which states that “the world’s foremost experts in the fields of comparative religion, history of religion, religious studies and sociology agree that Scientology is a world religion”, compiles works from renowned scholars on Scientology (including Beckford, Wilson, and Melton) to add emphasis to the Church of Scientology’s latest message to opponents: that Scientology is a legitimate religion, and as such should receive the rights of religious freedom.

This coupling of campaigning against discrimination and using the expertise of the academy to validate the religiosity of Scientology points to a Church that may be slightly more reserved than the one associated with ferocious legal battles, but is clearly still up for a fight. Time will tell how effective this new method will be for the Church of Scientology, but the conflict remains the same as it has for decades. The tactics may have changed, but both parties remain unchanged, and neither side is showing any sign of backing down yet.

References

Lewis, J. R. and Hellesøy, K. (2016) ‘Introduction’, in Lewis, J. R. and Hellesøy, K. (eds.), Handbook of Scientology, Leiden, Brill.

Not only is it important to consider contemporary religion in its historical context, but we need to consider the study of contemporary religion in its historical context too.

I recently attended a talk by Professor James Cox on cultural memory among the Australian Aboriginal people. In particular, Cox focused on the work of T.G.H. (Ted) Strehlow among the Arrarnte people, recording the traditions of the Elders. Many of these stories and rituals were later compiled in Aranda Traditions (1947) and Songs of Central Australia (1971). He was initiated into the tribe, whereupon several of his elderly informants confided in him that they could not rely on their sons or grandsons to preserve their stories, rituals or sacred objects (tjurunga). If not for Strehlow, almost all of these would have been forgotten a generation later, which Cox described as a break in the chain of memory (invoking the work of Danielle Hervieu-Leger). However, Strehlow’s work has allowed the current generation to relearn these tales and practices, in what Cox described as a process of “repatriation”.

No doubt, this is an empowering situation for present-day Arrarnte people, and important for addressing the problematic legacy of colonialism. But this set me thinking about the idea of a chain of memory. How do we know for sure that this was an ancient tradition? Might it have been the case that the elders had forgotten as much of the traditions of their forefathers as the present generation had of theirs? The fact is, without evidence, we are simply guessing. Worse, we are possibly making the rather colonial assumption that such indigenous people existed in a timeless state, essentially unchanged since prehistory – at least until they encountered Europeans.

There is a tendency to see the modern world as something special, a period which is dramatically and fundamentally different from all that has gone before. For all that we have gained, the argument goes, like technology, literacy, human rights, we have lost other things, like community, simplicity, perhaps even enchantment. Before we could blame it on the Internet, the Victorians harked back to a pre-industrial pastoral existence as they rushed into the soot-smothered cities, and the incipient scholars of the Enlightenment harked back to the pagan grandeur of Greece and Rome.

Ironically, then, separating our age from what has gone before is exactly what previous ages have done. Modern scholars are no different; indeed, the idea is there from the moment that we started to look at modern society seriously. Weber saw an iron cage of disenchantment; Durkheim saw the complexification of society leading to anomie and suicide; Frazer saw a progression from magic to science, whereas Müller saw a degeneration from natural, pure religiosity. The secularisation thesis has been refined and reformulated over time, but was originally based upon the teleological idea of an inevitable move from superstition to religion to science. Yet as we now know, it is increasingly difficult to make the data fit this argument.

Perhaps this is the issue: data. The further back we go, the more we are working with official data and less with the thoughts, deeds and ideas of ordinary people. Where there are primary documents, they are difficult to read at face value due to years of interpretation and even redaction. But when looking at the modern world, we are awash with data, drowning in it almost, from every level and section of society.

The study of contemporary religion is rich in ethnological specificity and deals well with change. What would a study of indigenous religion – or Medieval Catholicism, or the Classical world – which assumed not stability and tradition, but constant reformulation, innovation and diversification look like? Understanding contemporary religion in historical perspective might be an approach which helps us to understand the religion of the past as well.