By Suzanne Newcombe. Part 2 of a Series (read Part 1 here)

The concept of the Alt+R has become familiar with the ascendency of Donald Trump to the office of the President of the United States. The need for an alternative to the political and economic status quo is felt on all sides of political persuasions. What to do about this situation though, often appears harder to propose and even harder to agree upon. I will first describe the current ‘culture wars’ as a conflict between an Alt+R and a Ctrl+L – before arguing for the importance of teaching and using the methods of the Social Sciences and Humanities to navigate this environment.

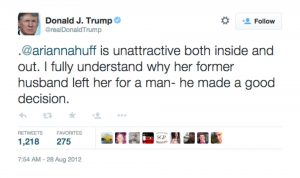

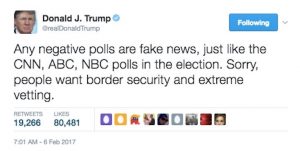

The Alt+R is associated with abrasive ‘plain-talking’ populist ‘truths’ and cries of ‘fake news’ when facts are interpreted with what is seen to be the wrong conclusion. The Alt+R uses a variety of strategies to delegitimize and silence opposing political views, from promoting its own ‘trusted’ and ‘unbiased’ sources such as Breitbart, Fox News and Citizen’s United political ‘exposes’ to decrying critical news sources as ‘FAKE NEWS’, to blatant ad hominem attacks, in the USA, against figures like Senator Rand Paul, Hilary Clinton or Arianna Huffington.

While this vitriolic discourse is more intense on the other side of the pond, there are echoes of it in European politics with the various populist movements from the English Defence League, UKIP, to France’s National Front to Greece’s Golden Dawn.

Although the Alt+R has embraced this term as one of positive self-identity, one can also identify what I will term a “Ctr+L” – those self-identifying on the left of the political spectrum who also attempt to silence opposition. At times, traditional media sources have described the Alt+R’s message as unsubstantiated conspiracy theories, discrediting the message without examination of the evidence.

University engagement in no-platforming and silencing of opposition through noisy protests and chants, removing the books of Holocaust deniers from open-access shelves, and an enforcement of ‘politically correct’ language, provides ammunition for the Alt+R’s impressions of the existence of a ‘liberal thought police’.

The Ctr+L is not above riots and violence, as events surrounding schedule talks of (then) Breitbart News spokesperson Milo Yiannopoulos at California Universities UCLA, Davis and Berkeley during early 2017 and some G20 protests have shown.

Photograph of a burning police cruiser at the G20 protests in 2010 which turned violent in Toronto. Image by Mark Mozaz Wallis (Creative Commons).

So what can we, as educators, do in a time when (apparently) the ‘authority of experts’ is derided?

We need to remember that the most important part of what we teach is PROCESS, not content. We don’t actually want our students to parrot our views, because we want our views to be challenged – with convincing evidence and logical consistency.

Every citizen needs to have the tools to inform themselves for public debate. Myself and my academic colleagues aim to do just that in our teaching. We want to empower our students to be able to become their own experts, and to accurately and critically evaluate the testimony of other ‘experts’. We teach that the testimony of experts should be evaluated on the merits of evidence and not simply because of a qualification or job title.

There is some evidence that people who have been trained with only technical competencies and respect for authority – and not in the skills of rhetorical discernment needed in today’s information-saturated environment – might be more vulnerable to ‘radicalisation’ and even terrorism.

Beyond educating individuals in critical thinking skills, as academics and teachers, we need to model and support our students in learning how to dialogue with those who have views radically different from their own.

This kind of encounter can occur unexpectedly in internet forums, where many type out opinions that they would hesitate to speak to someone face-to-face. As moderators and educators, we need help by helping our students to discern information from expressions of emotion, to promote dialogue and demonstrate empathy with all our students. Only when individuals feel recognized as humans are they open enough to consider evidence and arguments that might feel alien to their sense of identity.

In my field of study, that of minority religious movements, Megan Phelps-Roper has provided an excellent narrative of how to dialogue with and perhaps eventually change opposing views. Phelps-Roper grew up in the infamous Westboro Baptist Church, picketing funerals of homosexuals and fearing the hellfire and damnation that awaited everyone not part of her family’s church. But through a combination of empathy and debate, she grew to find her own mind. (See also her TED talk).

We need to empower our students to be able to find the own positions, and not be afraid of changing their opinions should evidence and argument warrant. There is no shame in revising erroneous views. This is something academics must model as well as promote in our students.

In this current period of ‘culture wars’, teaching the methods of Social Sciences and Humanities as we do in Religious Studies at the Open University is more important than ever. How to evaluate, debate and re-assess our opinions that are the most important skills we are teaching.