By Graham Harvey

Religious objects almost fill the British Museum. In galleries dedicated to Islamic and Asian cultures as well as those related to health and healing there are many artefacts made for religious use. There are large portions of temples from ancient Sumeria, Egypt and Greece. There are deity statues from the Pacific, ancestor masks from Africa and icons from Greece and Russia. A full list would be a long one! And if you search for religious terms in the museum’s website — or in the Google Arts and Culture site related to the BM — the objects displayed are abundant. “Faith”, for instance, appears to be a popular theme for curators and website organisers. This fact indicates more than the presence of objects that originated in religious contexts. It points to the employment of religion as interpretative lens in this putatively secular institution. Two recent additions to the British Museum increase not only the presence of religious objects but also of religious interpretations.

In collaboration with BBC Radio 4 and with a book publisher, the British Museum currently has a temporary exhibition “Living with gods” in its premier gallery, Room 35 beneath the imposing central rotunda. This brings together the 40,000 year old “Lion Man” sculpture from the Stadel Cave, Germany, with recently collected objects such as Jewish kippot (skull caps — one displaying affiliation with a football club), and examples of souvenirs brought home by pilgrims. In between the ancient figure and the contemporary souvenirs are items drawn from across the museum’s collections: e.g. Coptic processional crosses, Hopi kachinas, Islamic prayer rugs, Buddhist icons, a Hindu juggernaut, Zoroastrian and Protestant prayer costumes. Any one of these could generate lengthy discussion — just as they have generated considerable devotion.

For those of us interested in religion as a bodily and material practice, there is something odd about the exhibition. Despite the prevalence of materiality that make ritual acts central to religion, the exhibition is framed and structured by words which insist that religion is defined by believing. Most curiously, the final display board before the exit from Room 35 uses words like “indeterminate”, “ineffable”, “never seen” and “not accessible”. Admittedly, these are said of an (indeterminate) “it” but the presumption must be that they refer to religion, faith, gods and other putatively transcendent realities. Conversations with other visitors to the gallery suggested that I was not alone in finding this an odd conclusion to draw about rich material cultures. Indeed, overheard comments on particular items in the exhibition strongly suggest that at least some objects continue to engage people quite viscerally and directly. Thus, the “Living with gods” exhibition deserves wider attention.

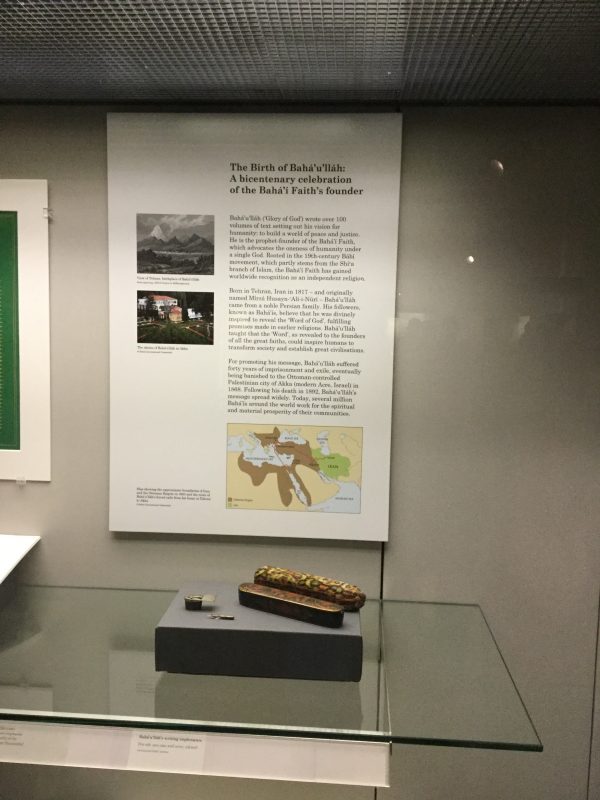

The second addition to the British Museum’s displays is a case commemorating the bicentennial of the birth of Baha’u’llah, the founder of the Baha’i Faith. Along with information about Baha’u’llah, the case contains objects owned by him, such as his glasses and pens, as well as examples of writings considered revelatory by Baha’is. It is placed at the rear of the museum’s Gallery of the Islamic World, devoted to “the cultures of peoples living in lands where the dominant religion is Islam”. The Baha’i Faith has spread worldwide and promotes a vision of global unity. The display case was the focus of considerable attention at a reception hosted in the gallery by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of the United Kingdom. A series of speeches emphasised key themes in Baha’i teachings and celebrated the perception that being able to handle the founder’s pens and correspondence provides an authenticity greater than that of other religions. The positioning, contents and response to this new display provide further encouragements to those of us interested in understanding the presence, practice and politics of religion in the contemporary world.