Theodoros Kyriakides and Richard Irvine.

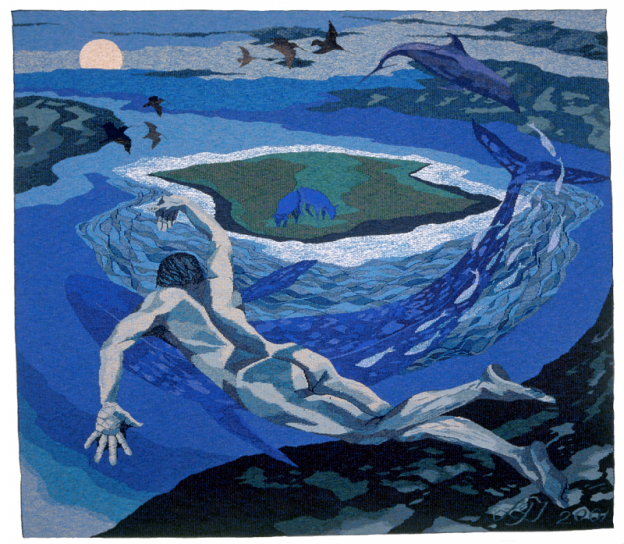

Eynhallow (Land of the Finn Man) by Leila Thomson (above). Tapestry at the Orkney Library, Kirkwall.

Eynhallow frank, Eynhallow free

Eynhallow stands in the middle of the sea

A roaring roost on every side

Eynhallow stands in the middle of the tide– traditional Orkney rhyme

“But what do you mean by magic?” There’s a long pause in the conversation; the anthropologist wonders whether they’ve asked the wrong question. “Well I suppose I mean… well, magic… like Eynhallow.” To those familiar with Orkney, this small ‘holy island’ is rich in stories: once upon a time a coming-and-going island, rising from the sea only to disappear, until it was won over from the shape-shifting finfolk by the use of holy salt. Still the island retains an uncanny quality: in 1990 two people were said to have disappeared into thin air after 88 were counted off an excursion ferry to the uninhabited island and only 86 were counted back on.

But it is not only the stories surrounding Eynhallow that make it a figure of magic. It is also the sense of it being simultaneously proximate, yet remote. It looms near, just between Rousay and the Orkney Mainland; and yet, surrounded by the elemental forces of the “roaring roost” – the riptides rushing past, the meeting point of the great energies of the Atlantic and the North Sea – it seems inaccessible. It fits perfectly with another explanation of the qualities of magic offered during conversation in Orkney: “a sense of wonder… but just out of reach”.

The question “What do you mean by magic?” is not a straightforward one. In fact, it is a question which can easily be turned back onto the anthropologist working on the topic. If you are someone just going about your daily routine, this is of course a very valid response to someone trying to research your beliefs and practices. Curiously enough, the fact that magic is such an open category makes this a rich question for our research in Nicosia and Orkney. Magic means different things for different people: magic for some might denote spells. For others, it is a quality of the landscape. For others, psychic readings. For others, Harry Potter movies. In other words, the question “what do you mean by magic”, far from suggesting that ‘magic’ is an irrelevance, indicates the polysemy – the rich and varied range of meaning – this word has acquired in modernity.

At the same time, this question reveals the enigmatic stance people adopt in the presence of the suggestion of magic: it is, in this sense, a topic “just out of reach”, surrounded by opacity and uncertainty. In The Empty Seashell, an ethnography of witchcraft in Indonesia, Nils Bubandt writes that “the fundamental unknowability of the other” often acts as a prerequisite to the manifestation or suspicion of witchcraft. Witchcraft is hence emergent from the fact that we cannot ‘see through’ the intentions of others. On the one hand, such witchcraft is indented in the workings of a society: it proceeds through specific instances, practices, rituals and social structures. On the other hand, the forms of magic which emerge within our fieldwork showcase how magic in contemporary societies takes multiple forms, reflecting the pluralism of beliefs and habits.

Here, we encounter a different kind of “unknowability” to once again use Bubandt’s term of choice. To return to Orkney, on the island of Rousay ideas of ‘magic’ in the landscape are attested to by the many stories which surround the Neolithic chambered cairns and standing stones. The folklore attached to these places is rich and well recorded. Yet, importantly, many layers of unknowing intervene in any given ‘encounter’ with the storied landscape: Protestant Christian attempts to rid the populace of superstition; population displacement due to clearance and emigration; population change due to incomers from beyond Orkney; secularisation. None of these strips the landscape of its potency, but each contributes to its sense of being ‘out of reach’.

Working back through these layers to understand the occluded landscape seems to generate new forms of interaction: for example, given the closure of the island’s kirks and the decline of island churchgoing, it is not altogether surprising that an archaeological site should become the setting for an island wedding rather than the kirk. Meanwhile, in recent decades modern standing stones have joined their ancient counterparts. The work involved in quarrying and erecting such stones makes this by no means a flippant undertaking, though neither is it a phenomenon that in all cases can be taken too seriously. Modern stones might be said to be “watching over us, helping us as they’ve always done”, but in another case might be said to have been erected more playfully, a landmark to direct tourists to what was built as a holiday home.

- modern standing stones in Rousay

So, expanding on Bubandt’s idea of unknowability, the opacity of magic in modernity does not only mean that one is not sure of others’ intentions – it can also imply that people are never too sure of what magic might mean for them, or even if they ‘believe’ in it. Take the example of the Cypriot non-believer who still puts faith in his or her lucky pendant under situations of play. Or, the example of someone who does not attend church but finds herself reciting a trio of prayers under a certain situation of distress (one for each member of the Holy Trinity). On such occasions, pendant and prayer are both granted a semblance of automatic efficacy which Marcel Mauss identified as a central tenet of magical belief.

Why do people entertain such halfhearted beliefs if they don’t really believe in the efficacy of magic? When we ask this question, we notice that the people we talk to approach the suggestion of magic, much like their belief in it, in indirect manner. In Cyprus, many do not explicitly believe in magic, but nevertheless find that magic often occupies part of daily stories and rumours they hear, and also of childhood memories. We hence often find that we are conducting a kind of archaeology of magical beliefs, working through strata of unknowing. Magic is, nowadays, concealed under several temporal layers of personal and collective amnesia, but also recollection. We also find, however, that such social conditions don’t necessarily dilute the notion of magic amid increasing narratives and processes of unbelief and secularism, but rather grant it a vague semblance of autonomy and unpredictability. In such sense, conditions of social, political and financial uncertainty – characteristic of contemporary societies – can be understood as not erasing but rather as producing (or maybe reproducing) particular forms of modern magic. It is a world where something is left partially ungrasped and out of reach, just enough for it to keep returning.