Police Sociability

The training, the uniform, and the fact that most officers were of working-class origin – cut off from senior officers at Scotland Yard who were often upper-middle class military men, and cut off from the working-class community that they policed – contributed to the development of a distinct occupational culture. Part of this was fostered by practical training on the beat, which led to police practices that often diverged from the strict guidance of the rulebook – something that will be seen in the module on crime. Life outside work also strengthened bonds between brother officers.

Initially, married men were favoured as recruits since they were believed to be more stable and to embody respectability. Married men were also believed to be less susceptible to the temptations on offer in a city – such as bribery. Proof of police corruption was often difficult to obtain, though memoirs and various other sources brought together by historians suggest that corruption with respect to betting was systemic throughout the force in early-to-mid twentieth century London. Official reports show that complaints were investigated, but that evidence was difficult to secure. Two examples are provided: one for alleged corruption and the other for bribery associated with street betting.

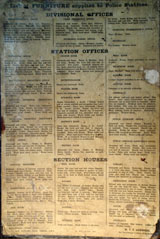

Well before the end of the nineteenth century, however, single men were favoured as recruits. Indeed, in the inter-war years, a man had to have served for at least four years before he could obtain permission to marry. Yet having young, single men stationed in an urban area had the potential to create disciplinary problems. The single men were often housed in section houses. The section house generally consisted of a common room, a shared kitchen and dormitories; by the early twentieth century many of the dormitories had been converted to cubicles. A badly damaged document from the 1920s shows how a section house was kitted out. A price guide from 1895 lists provisions that could be purchased from a section house linked with a Bow Street ('E' Division) section house.

Some of the rules were strict. For example, during the nineteenth century, officers had to attend church and permission was needed for night-time absence. For much of the twentieth century single women were not allowed on the premises.

Arthur Battle’s memoir highlights the camaraderie that existed among police officers. This camaraderie extended to mutual assistance to aid injured and sick officers. Former PC Reuben Webb, of the 'W' (Brixton) Division, was discharged after seven years service, following the development of rectal cancer. He was unable to perform even light duties due to an inability to bend or lift items. There were concerns that any prospective employer would refuse to employ him as uninsurable. His brother officers wished to establish a subscription fund to allow him to set up his own tobacco and confectionary business, which the commissioner approved. The policeman's lot, however, was not always a happy one.

William Edward Pearce 1853-1883

William Edward Pearce 1853-1883