Biased Policing: The Battle of Cable Street

During the inter-war period, rather than simply having to suppress a demonstration, the police often found themselves between opposing political groups. One of the most famous instances of this was the battle of Cable Street on 4 October 1936, when crowds of people assembled to block a march by the British Union of Fascists (BUF) through the East End. The East End contained the largest concentration of Jews in the United Kingdom. This was the climax to a wave of BUF demonstrations in 1936 and on this occasion over 250,000 people assembled to prevent Oswald Moseley’s blackshirts from marching through their district. Over 10,000 police officers were drafted in to manage the confrontation and potential disorder. Over 150 people were arrested and 100 injured.

There were concerns voiced by many on the Left that the police were sympathetic to the BUF and that many officers were avowedly anti-Communist. Little direct evidence points to personal viewpoints held by individual officers, though some oral testimony suggests police heavy-handedness towards Jewish men and boys in the crowds. Recent research emphasises that, in the early 1930s, the police concerned themselves with threats from the Left to public order. The first meeting by the BUF took place in October 1932 though, from the following year, BUF members paraded in the East End selling newspapers. The selling of newspapers did not break any laws, but the police were aware of the sensitivity of the issue. A number of blackshirt newspaper vendors were arrested for causing a breach of the peace. The Metropolitan Police Act was also invoked to arrest people using anti-Jewish language under its clauses covering insulting words and behaviour. In his memoirs PC Battle portrays the work of the police in a positive light.

But if the police did show some sympathy for one side, they acted with the full support of many others in authority. Detective Inspector Brunsden informed F.O. Langley, the magistrate at Old Street Police Court, that he would be seek remands in some cases. The magistrate replied that he wished 'to make it perfectly clear that I am entirely behind the police in any remedy they may ask for'. Mr Harris, a magistrate at Thames police court also covering the East End, remarked: 'The very people who had been protesting against the Fascist procession on the ground that it would cause a disturbance form themselves into an anti-Fascist procession. That is what I cannot understand.'

The Public Order Act, passed in the wake of the disorder, increased police powers over demonstrations, and banned both the wearing of uniforms and the use of insulting or provocative language in public meetings. Many on the Left harboured suspicions, not unjustified, that the Act was aimed at curbing the activities of the Left as well as the Right.

There is no record of any baton charged being used against the BUF, though they were used on numerous occasions on their opponents. The police faced a dilemma: on the one hand the fascists were provoking local Jews and communists, on the other hand they claimed defence of their rights to assembly and free speech. Probably some sympathies were harboured towards the fascists more than the communists, as the former were often thought to be less of a threat to law and order.

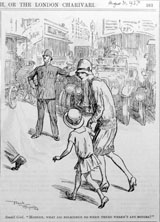

"Mother, what did policemen do when there weren't any motors?"

"Mother, what did policemen do when there weren't any motors?"