Order on the Street

The module on the origins of the Metropolitan Police noted how the parish watchmen had assumed an increasingly professional role by the 1820s. This professionalism coincided with the advent of street lighting. The use of gas to light the streets was first tried in Pall Mall in 1807. It was followed by a major extension of street lighting in the years after 1814; St James's Park, for example, got its lighting in 1822. Street lighting sharpened the concern with behaviour in open spaces at night-time; and the wealthy and respectable were increasingly reluctant to see new and elegant streets, especially those in the expanding West End, cluttered with the detritus of markets and butchers shops, not to mention beggars, drunks and prostitutes. Thus the expansion and professionalization of the watch in the early nineteenth century was a significant moment in the transformation of the term 'public'. The establishment of a centralized police force confirmed that community and customary definitions of what constituted appropriate behaviour were being replaced by more uniform and tighter definitions of legality in public. The 'public' arena was an increasingly selective and bureaucratic definition made by those in positions of public authority that increasingly had agents, first professional watchmen, but then the new police to enforce their regulations.

Unfortunately, the remit of the police to maintain order on the streets led them into confrontation with the working-classes who conducted a great deal of their business on the streets – most notably buying and selling from tradesmen with barrows. The friction between the policeman and the costermonger became legendary and continued well into the twentieth century. A key part of the problem arose from the fact that a barrow, in a street, created an obstruction and the police were charged with ensuring the free flow of traffic. Markets also attracted heavy policing to reduce the potential for disorder from the sheer number of people present and the heavy traffic. A series of reports from the superintendent of 'E' Division to the commissioner between 1869 and 1887 are illustrative of the problem. See the extract from the report of 1870.

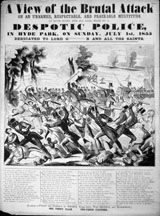

Much buying and selling on the streets, of necessity, took place on a Sunday. Men were commonly paid their weekly wage on a Saturday, and Sunday was the day on which they did not have to work. For many among the respectable middle classes, however, Sunday was the Sabbath, a day of rest when commercial activity should cease. In 1855 Lord Grosvenor introduced a bill to increase restrictions on Sunday trading. Mayne, the Police Commissioner, opposed the legislation as likely to cause significant tension between police and public. Nonetheless, there was a major demonstration in London that quickly got out of hand. The police were ordered to intervene. The press reported police brutality against the crowd and a subsequent Royal Commission criticized the management of the police. This handbill is typical of the condemnation of the police.

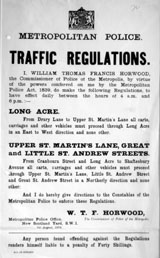

Over the course of the century, the police's remit over a wider range of social affairs grew. For example, the Metropolitan Streets Act of 1867 led to further regulations concerning street trading and traffic control, and made the muzzling of dogs in public mandatory. This law was soon dropped due to lack of public compliance.

While the conflicts between street traders and police officers continued, they were reduced by the decasualization of employment practices, and a reduction in the use of the streets as a centre for leisure.

At the same time, traffic became an increasing headache for the police, depicted by a cartoon in Fun in 1864. The problem of preventing working-class street traders from creating an 'obstruction' has already been noted. Infringement of these regulations could lead to a fine of 40 shillings [£2] – equivalent to the weekly wage of a female shop worker in the late 1920s. The spread of the omnibus, first horse drawn but then, by the early twentieth century, motor-powered created new problems. The private motor-car created many more and, for the first time, it brought the police regularly into conflict with the respectable classes. From the beginning of the twentieth century there was suspicion about the police using underhand tactics to charge motorists with speeding. A photograph from the early 1900s depicts three policemen, one uniformed, two in plainclothes with stopwatches. The two plain clothed officers would stand a measured distance from one another on a road and time motorists over that distance. If found speeding, the second plain clothed officer would signal with a hanky to the uniformed officer who stood further down the road and he would stop the vehicle.

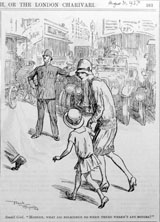

In addition to regulating motorists' behaviour the police also had to regulate the increasing number of vehicles on roads that had rarely been designed for them. Before the widespread creation of traffic lights busy junctions were regulated by police officers on 'point duty'. In August 1927 the satirical periodical Punch picked up on the police responsibility for traffic regulation with a cartoon: "Mother, what did policemen do when there weren't any motors?"

Fraught relations with the public, and particularly the rougher elements from the poorest districts of the metropolis, are reflected by the number of assaults on police officers. While the number of assaults had dropped since the 1860s, 2,291 officers were injured in 1895, accounting for the majority of policemen's injuries at work: The figures stabilized at 2,867 assaults (1900), 2,703 (1905) and 2,492 (1910). By the 1930s the Commissioner's Reports list only the number of days lost due to assaults on the police, yet between 1920 and 1927, an annual average of 2,421 policemen were assaulted in the metropolis per annum, amounting to 12 per cent of the force. One such example is the case of PC 487 Sutton.

Some officers were hard men, and were deployed in rough areas specifically because of this. But it would be quite misleading to believe that officers always looked for trouble. Beat officers spent an eight-hour day on their feet, doing a mainly monotonous job. The memoirs of Arthur Battle provide interesting reflections on the realities of policing. Even in the rough district of 'G' (Finsbury) Division, serious violence was rare. On the one hand, officers were prepared to administer summary 'justice' to young men who hung around on street corners, showing a lack of 'respect' to officers. On the other hand, when serious trouble broke out, many officers were loath to resort to violence. Battle recalled that he only used his truncheon once during his entire career.

While public order includes decorum and good behaviour on the streets, it is major political demonstrations, strikes, picketing and riots that are usually seen as public order problems. And it is to these issues that we now turn.

"Mother, what did policemen do when there weren't any motors?"

"Mother, what did policemen do when there weren't any motors?"