I have had the great honour of seeing my collection Thérèse: Poems published this month (September 2020) by Paraclete Press, a US publisher with a small but striking poetry list, including books by Scott Cairns, Sophia Starnes, and (forthcoming) Laura Reece Hogan. Thérèse might seem like an odd choice for a twenty-first century poetry project, so I’d like to explore my reasons for writing about her – if indeed ‘reasons’ are to be found.

Thérèse Martin (1873-97) was a French Carmelite nun who died young in the small Normandy town of Lisieux. Although she lived a brief and decidedly unremarkable life, she was canonised in 1925. Those of you who were brought up Catholic (I was not) might associate her with somewhat simpering art and statuary, and an equally simpering spirituality. Her life and writing were presented through a decidedly saccharine filter for at least the first half of the twentieth century, and indeed images of Thérèse as an anodyne rose-clutching nun still widely persist. But through all the years I have heard and read about her, something has caught at my wayward heart, for want of a better way of putting it. A couple of things finally prompted me into engaging with Thérèse in the way I knew best: writing poetry.

I do have a bit of form in writing about spirituality. I have a longstanding connection with Julian of Norwich and the Julian Centre in Norwich where I used to work, and have written essays and lectures about Julian, and a poetry collection about her fellow medieval Norfolk visionary Margery Kempe too (in Ink’s Wish). Three years ago, I set up and edit Amethyst Review, an online lit journal for new writing engaging with the sacred. But I also have a background as a bit of an experimentalist in poetry (including two collections with Shearsman) and still like to read, write and generally encourage innovative work.

So why Thérèse? The first aspect of Thérèse that interested me was the wealth of detail available about her constrained life. A writer herself, her own memoir (The Story of a Soul) records many luminous incidents which lend themselves to poetry. The smallest of gestures, images and experiences are there to be pondered over, such as Thérèse’s description of once taking the elevator, as a teenager in a Parisian hotel, or of being splashed with dirty laundry water later on in the convent. Both of these moments became prompts for poems.

These are hard days:

the sodden sheets, robes, scapulars

are scrubbed with salt and ash

and now need rinsing,

rolling, beating, rinsing again,

in the convent’s wash-house pool.

(from ‘Laundry’)

Thérèse herself was fond of the word ‘little’ and to me the relatively minimal nature of lyric poetry felt a good fit for reflecting on her life – small and constrained in outward form, but pointing towards a much larger dimension through its necessarily careful use of line and phrase. Thérèse is also, famously, a saint of simplicity (she once claimed that reading weighty spiritual texts just gave her a headache) and so I sought a simplicity of style, consciously diverging from my poetic approach to the eccentric Margery Kempe. Thérèse cherished humility but was also ambitious – for example, despite the gendered restrictions of her era, she harboured longings to be doctor, priest, and missionary; she was good-humoured and sweet-natured, but also a tough mentor to the other novices – and I found myself caught up in paradox as I considered her life. And while she is sometimes thought of as childish, the way she bore with her own illness and periods of despair was gritty and heroic. I struggled with whether and how to depict this in poetry, wanting neither to minimise her trials, nor become what Heaney might describe as an ‘artful voyeur’ of the suffering of another. In the end, I just wrote the poems that wanted to be written.

Little Lamp

Little lamp, whose wick

she pulls up with a pin

flickers in the dark night,

is a little spark

in which she kindles

a few more little words,

little glass inkwell

in which she spits

to make the blackness

last a little longer

lets her write

her little scraps of faith

traced with ink and blood

in the dark June nights.

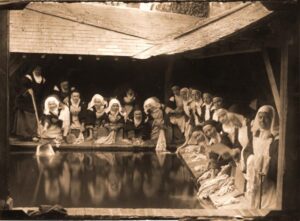

Secondly, Thérèse is one of the earliest saints to be photographed. Alongside Saint Bernadette of Lourdes, she is the best-known female saint of the nineteenth century partly because of the photographic images that remain. Many of these were taken by her own sister Céline, after she too became a nun. Photography in the 1880s and 1890s was a laborious process, requiring nine seconds of exposure and hours of subsequent darkroom development, yet Céline still managed a variety of memorable shots featuring or including Thérèse – some are sombre and posed, others capture the otherwise hidden happiness of a women’s community at work and recreation.

Some look at the camera in its box,

as the slow photo’s taken,

their eyes meet ours across

more than a hundred sepia years

and they darn and daub, and smile

at long-gone comments.

(from ‘Recreation in the Alley of the Chestnut Trees, 1895’)

Finding all of the extant photos of Thérèse online a few years ago led me to dwell on them and to some extent in them, caught by their simultaneous alterity and familiarity. I found myself drawing on the poetic practice of ekphrasis, feeling my way to a balance between visual description and imaginative reflection. I’ve even been able to include a few of the photos in my book, thanks to permissions from the Archives and Office Central de Lisieux.

I was fortunate to be invited to submit my manuscript to Paraclete’s poetry editor and have been impressed by Paraclete’s careful editing and production process. My hope is that the collection works both as a biography in verse, and as a gathering of individual poems that each seek to say something about Thérèse’s life, time, and paradoxical sanctity.

Snow

The snow she’d always loved –

delicate and white,

winter blossom, heavenly

host melting on the tongue;

each communion unique

and given freely – so

she dared to pray for snow

to mark her vows, prayed to be

given to the cold; resolved

to the filigree of soul-work –

dissolved at the ushering

of the sky’s breath.

Dr Sarah Law is a tutor for the Open University’s MA in Creative Writing. Follow her on twitter @drsarahlaw