What is engaged research?

Public engagement with Higher Education research (often shortened to HE-PE) is all about the different ways universities engage the wider public with their research and activities. The goal isn’t just to inform people, but to build positive, two-way relationships between universities and communities. According to the UK National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, it should involve genuine interaction and listening, with the aim of generating mutual benefit (NCCPE, 2020). Many UK academics feel a strong moral obligation to get involved in public engagement, and participation is often based on intrinsic rewards, such as wanting to share their research with broader audiences (Watermeyer, 2016), but academics also need to see how it benefits their own personal and professional development. Whilst most academic researchers agree that HE-PE should be based on a two-way relationship in practice it often follows a ‘deficit model’ approach, where academics decide what to share, when, and how, and the public is expected to just take it in (Grand et al., 2015).

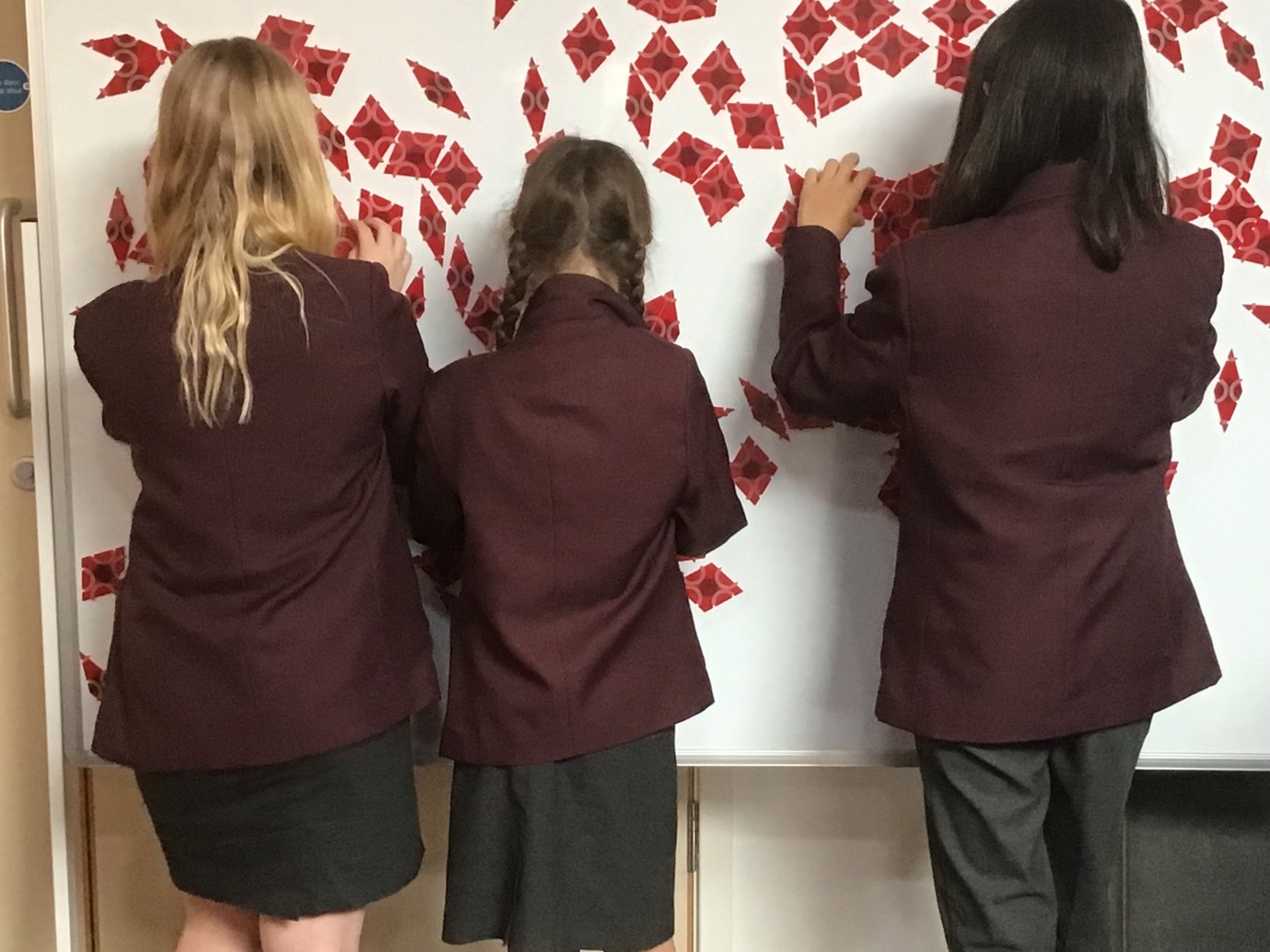

School students engaging with tiling puzzles at the Open University Aperiodic Tiling exhibition

Over the last decide, universities have been encouraged to rethink how they engage with the public, to not just present research to audiences, but to work with and include publics in the creative process (Grand et al., 2015). This is where engaged research comes in, a concept coined by Open University researchers (Holliman et al., 2015). Rather than one-off events or top-down communication, it’s a more intentional and collaborative approach. Instead of academics doing the research in isolation and then sharing it afterwards, engaged research brings in community members, stakeholders, or even school students as collaborators at different stages of the research, including sometimes at the very start of the research process (Holliman et al., 2015). It’s about breaking down the barrier between expert and audience and creating a more equal, inclusive way of doing and sharing research. Researchers and the public work together to ask questions, gather data, and make sense of the results. Everyone brings different experiences and knowledge to the table and different forms of knowledge, not just academic knowledge, are treated as valuable. Engaged research is built on relationships, trust, and shared learning.

The challenge is that it is not easy to achieve engaged research. According to Holliman et al. (2017), engaged research can take more time, more effort, and is often far more labour intensive than traditional academic research. It requires planning, communication, and can require a willingness to let go of control. Barriers such as research funding, short timeframes or university policies can make it difficult to plan for engaged research. For these reasons, some researchers still prefer to continue with more established models, because they feel simpler or more familiar. This means the most common kinds of HE-PE are still one-way, ‘top-down’, events including researcher led lectures, masterclasses, and demonstrations.

Why is it important to move beyond the deficit model of HE-PE?

Whether they are aware of it or not, academic researchers in mathematics and statistics hold power over the knowledge they create through their research. For example, they not only choose what to research (though this can be constrained by research funding) but they also make decisions about how to develop this research, whether to involve non-academic stakeholders in the planning process or data collection stages (Medvecky, 2018). They also choose how the research is shared within academic and non-academic communities, including which journals to publish with, which science fairs to present at, which schools or community groups (if any) to visit etc. This means that researchers have a responsibility to consider epistemic justice, or fairness in knowing, that is, to consider how the knowledge they create is equitably distributed and beyond that, to make sure it is created fairly.

The concept of epistemic justice was developed by British philosopher Miranda Fricker (2017) to describe the ethics of knowledge production. It describes a fairness in the way knowledge is shared, created, and valued. In simple terms, it’s about making sure everyone has a fair chance to know things, and to be recognised as someone worth listening to.

Fricker (2017) describes two main types of epistemic injustice: Testimonial injustice and Hermeneutical injustice.

Testimonial injustice happens when someone’s knowledge or experience isn’t taken seriously because of who they are, or in contrast when someone’s knowledge is overly trusted because of who they are. For example, a professor in mathematics may be considered an expert over a hobbyist mathematician, even if the topic in questions is outside of the professor’s expertise and the hobbyist has a great deal of knowledge in this area. If the hobbyist’s opinion is dismissed because they are seen as a non-expert, that’s a form of testimonial injustice.

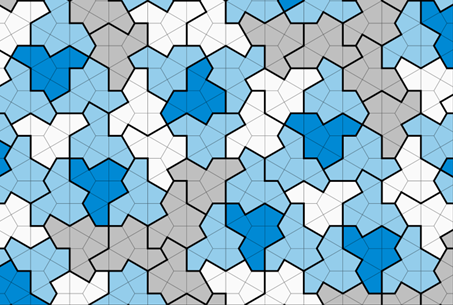

In 2022, a retired print technician and amateur mathematician, David Smith, showed the value of non-expert knowledge by making a significant discovery in the field of aperiodic geometry through creating an aperiodic monotile: a single aperiodic tile which could tile the plane. This discovery helped solve the previously unsolved Einstein problem.

Hat tiling created by David Smith

Hermeneutical injustice is when people don’t have the tools, language, or opportunity to fully understand or express their experiences. In a mathematics and statistics research context, this might mean not being supported to ask questions, challenge assumptions, or explore new ideas. For example, when a new mathematical discovery is made, if it is shared only in academic journals, using very technical language, public audiences may not have the tools to understand or question the discovery.

When universities rely on traditional models of public engagement, groups like school students, community members, or hobbyists can be unintentionally excluded from sharing their knowledge or from being able to learn, question and critique new knowledge. Not because they don’t have anything to offer, but because they aren’t always seen as serious contributors or given the opportunity to contribute. That’s not just a missed opportunity to learn from different groups of people and to expand knowledge production and exchange, it is also a form of epistemic injustice.

Holliman (2019) suggests that engaged research can help tackle issues of epistemic injustice by opening up space for more people to be seen, and to see themselves, as knowers. It values different ways of understanding the world, not just what’s published in academic journals. And that makes research fairer, more inclusive, and often more relevant to real-life challenges.

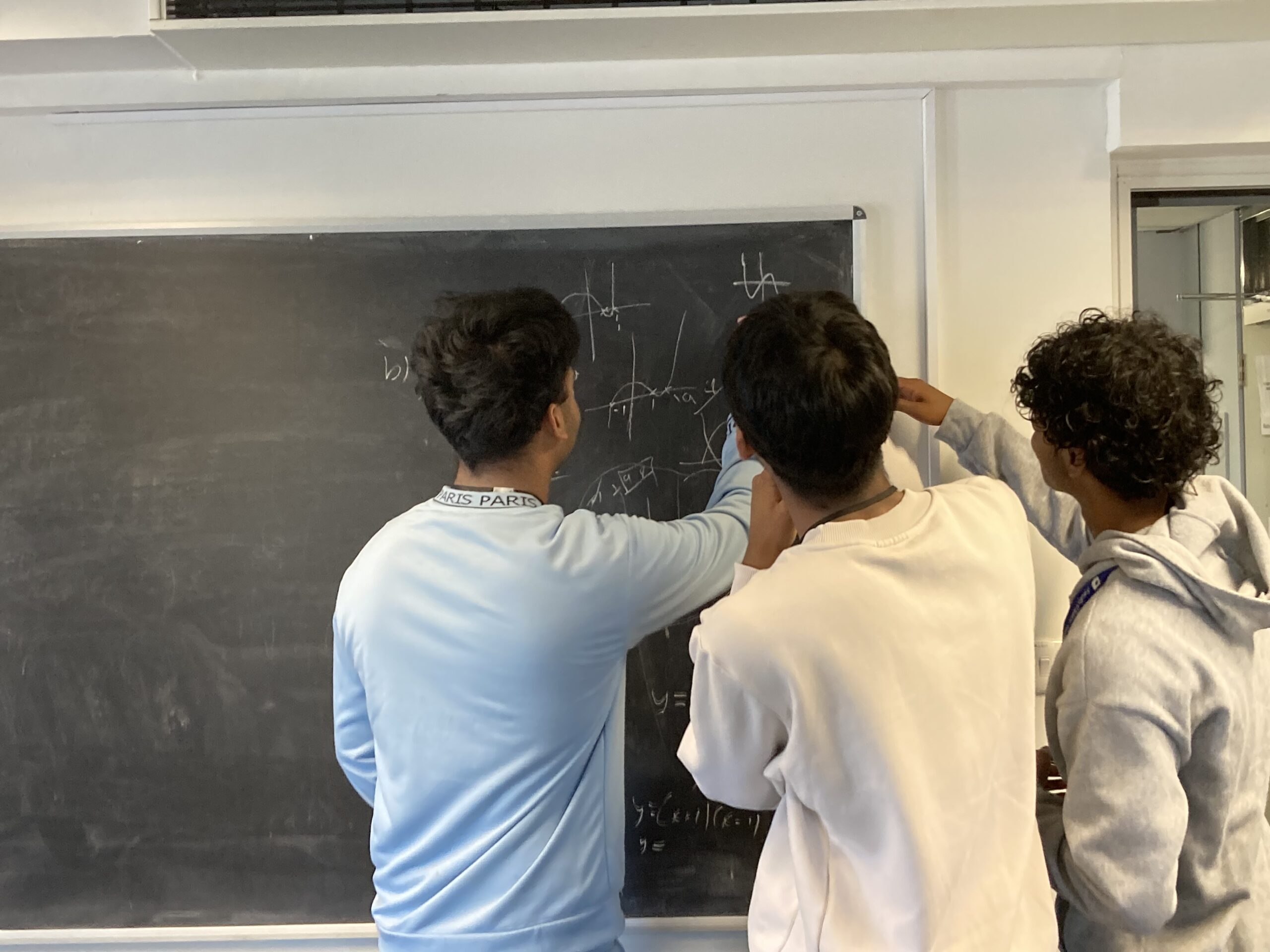

A-level students working on mathematical research at the Open University

Further reading

Rick Holliman, Professor of engaged research, gave his inaugural lecture entitled ‘Fairness in knowing’, about engaged research and epistemic justice. You can watch and read it here: Fairness in knowing’: How should we engage with the sciences? | The Open University

References

Fricker, M. (2017). Evolving concepts of epistemic injustice. In The Routledge handbook of epistemic injustice (pp. 53-60). Routledge.

Grand, A., Davies, G., Holliman, R. and Adams, A. (2015) ‘Mapping Public Engagement with Research in a UK University’, PLoS ONE, 10(4) pp. 1–19.

Holliman, R., Adams, A., Blackman, T., Collins, T., Davies, G., Dibb, S., Grand, A., Holti, R., McKerlie, F., Mahony, N., and Wissenburg, A. eds. (2015). An Open Research University. Milton Keynes: The Open University.

Holliman, R. (2019). Fairness in knowing: How should we engage with the sciences? The Open University, Milton Keynes. Online: http://oro.open.ac.uk/60416

Medvecky, F. (2018). Fairness in knowing: Science communication and epistemic justice. Science and engineering ethics, 24(5), 1393-1408.

National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (2020) What is Public Engagement? Available at: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/about-engagement/what-public-engagement.

Watermeyer, R. (2016) ‘Public Intellectuals Vs. New Public Management: The Defeat of Public Engagement in Higher Education’, Studies in Higher Education, 41(12), pp. 2271–2285. Doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1034261.