On Friday 9th March, we hosted the very first Open University Mathematical Resilience Day for students in year 9 in the Hub Theatre on campus. The day was aimed primarily at girls with a focus on building their mathematical resilience. Students from schools in and around Milton Keynes were invited to attend the event, which was funded by a grant from the London Mathematical Society (you can find out more about the LMS here: https://www.lms.ac.uk/).

Throughout the day, our focus was to support students to develop as resilient learners, through working together and discussing strategies to help them when they found the mathematics challenging. Alongside working on mathematical problems, we discussed three key aspects of mathematical resilience:

- Growth zone model

- Growth learning theory

- Growing mathematical resilience

The students started the day by completed an attitude to learning questionnaire, based on the Fennema-Sherman Mathematics Attitudes Scales, encouraging them to think about the way they think about learning.

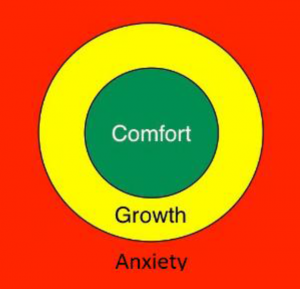

1. Growth Zone model

Clare introduced the Growth Zone model, a concept introduced in her work on mathematical anxiety and mathematical resilience

In the GREEN zone you are comfortable. You might be consolidating some ideas but you are not learning.

In the YELLOW (or amber) zone you are learning, but learning feels risky and a bit uncomfortable, there are barriers to overcome, there is some struggle and you have to perserve to be able to “get it”. Stay here as long as you can, you will learn more that way, but don’t stay too long.

In the RED zone the risks feel too great, you feel unsafe and anxious. The barriers feel too much, you just cannot do this. You need help. Don’t be afraid to ask for what you need.

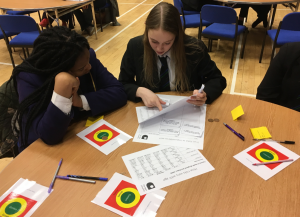

Working on some mathematical problems using the Growth Zone model

The girls were encouraged to use their “growth zone” models throughout the day to chart how they felt about each activity and to help them to talk about their feelings in relation to the mathematics they were doing.

You might like to have a go at the task below yourself. If you do, why not chart your feelings using the Growth Zone model shown above?

Task: 9 coloured cube

If you have 27 cubes, 3 each of nine colours (e.g. 3 yellow, 3 blue etc).

Can you make a 3 by 3 by 3 cubes so that each face contains exactly one of each colour?

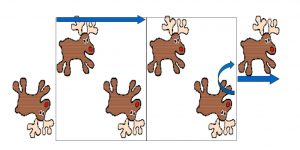

The image above shows a cube with two faces that meet this criteria, but unfortunately on the third face there are two green cubes and two black cubes, so this is not a solution.

You can find this task, and other similar problems here: Nrich.org.

2. Growth Learning theory

Clare explained that, according to Growth Learning theory, there are two ways in which people think that they learn:

1.Fixed Theory of Learning: I can only learn just so much, no matter what help and support I get I really won’t make much progress in maths.

2.Growth Theory of Learning: I have the confidence that I can develop mathematical skills. I know that everyone can learn more mathematics with effort from themselves and support from others and that includes me.

Neuro-science tells us that the brain grows every time you use it – it makes more synapses and connections but if you don’t use it those connections are pruned. Grow your brain!

“Being Stuck is an honourable state”

John Mason, Emiritus professor at the Open University, wrote in 2014: “Everyone gets stuck sometimes, and it can be frustrating, even debilitating rather than stimulating. However, being stuck is an honourable and useful state because that is when it is possible to learn about mathematics, about mathematical thinking, and about oneself”.

We discussed the importance of “being stuck” in mathematics and talked about the fact that even very successful mathematicians get stuck sometimes. For instance, world-famous mathematician Andrew Wiles, who gained fame by solving a nearly 400-year-old, previously “unsolvable” problem: Fermat’s Last Theorem, recently spoke in an interview about the “state of being stuck”. In this interview, Andrew Wiles was asked what advice he would give to the general public about mathematics, his answer was “accepting the state of being stuck.

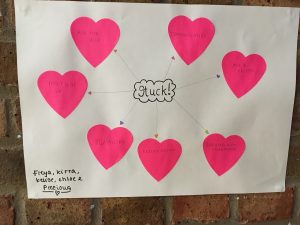

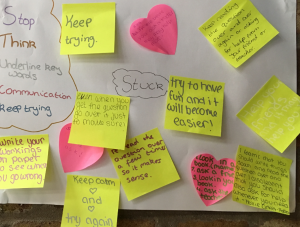

Having identified that “being stuck” would be inevitable at some point and reflecting on the way they worked together, the girls created “STUCK” posters, which were filled with advice for themselves and others, including “Don’t give up”, “Teamwork is key” and “keep practising”.

One group came up with an acrostic poem to help students when they are STUCK:

- Stop

- Think

- Underline key words

- Communicate

- Keep trying

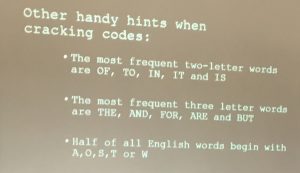

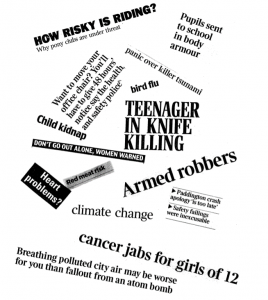

Having the confidence to question what you read: Numbers in the News

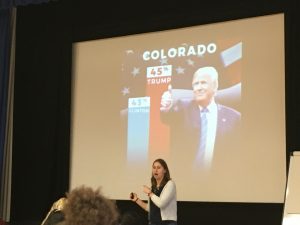

After lunch students were treated to a talk entitled “Numbers in the News”, given by Zoe Griffiths from @ThinkMaths who showed them misleading graphs and charts used in newspapers, leaflet campaigns and social media to give biased information. Her aim was to show the students that they can learn to use mathematics to critically review the information that they read and hear about.

Zoe also talked about the importance of knowing sample size and methods of data collection used before deciding whether a claim is credible.

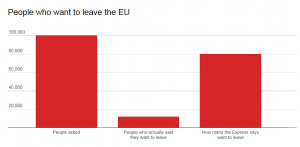

For example, one newspaper claimed that 80% of people wanted to leave the EU. Looking into the detail of the poll, data was collected in only three constituencies and a leaflet campaign preceded the poll. In addition, out of 100,000 people who were asks, only 14,851 responded to the poll, of which 11, 706 voted to leave. This graph, published by the Independent online, demonstrates the newspaper’s claim and the actual quantities of responses.

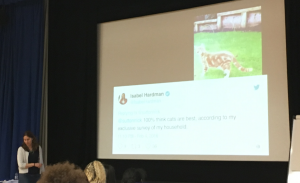

To further exaggerate the point, Zoe showed a Tweet claiming that “100% think cats are the best” (from a sample size of two: one person and their cat).

Zoe’s talk emphasised the importance of having confidence in our own mathematical abilities in order to interrogate data presented to us in the news, social media and advertising.

She finished the session with a demonstration on not being fooled by “special offers”! Girls were tempted with winning £20. I won’t spoil the game here, but you can get in touch with Zoe to find out more! @thinkmaths

You can find out more about the talks Zoe and her team offer for schools and events here: http://www.think-maths.co.uk/.

Student task: Analysing the validity of newspaper claims

Following Zoe’s talk on interpreting data in the news, the girls were given a task to identify whether there was enough evidence to support claims made. The students worked together, using strategies from their stuck posters to support each other, to organise and interpret the data given and to justify their decisions.

Have a look at some of the statements below

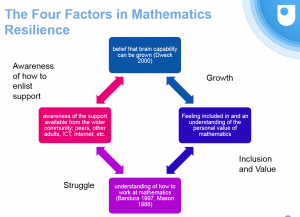

3. Growing mathematical resilience

Finally we invited the students to reflect on whether they have mathematical resilience. Clare explained that, if you have mathematical resilience you will:

- seek to stay in your growth zone, get help when you need it and avoid the red zone where you know you cannot think;

- feel part of an inclusive community of those who are learning mathematics and understand the value of doing so;

- know that sometimes there are barriers to understanding mathematics which you have to struggle over;

- persevere, knowing how to overcome difficulties, and how to get the help that you need;

- work collaboratively with your peers giving and receiving help to push ideas forward;

- work to use the language needed to express what you understanding, misunderstand and to ask questions;

- have a growth theory of learning, that is you will know that the more you work at mathematics, with support, the more successful you will be.

To summarise, in order to be able to develop Mathematical Resilience you need:

- To believe that brain capacity can be grown (Dweck, 2000)

- To have an understanding of the personal value of mathematics

- To understand how to work at mathematics

- To have an awareness of the support available from the wider community, including: peers, teachers, school resources and the internet.

Reflecting on the day

The students reflected on what they had learned throughout the day, returning to an attitude to learning survey which invited the students to review whether their feelings towards leaning had changed as a result of the activities and discussions throughout the day.

Here are some of the questionnaire responses to the question: Has anything changed in your beliefs concerning learning mathematics?

“That if I believe in myself I can do it.”

“Maths is not that difficult if you ask for help and try it.”

“I shouldn’t give up! I should keep on trying!”

When asked to write down the three key ideas which the students felt helped them solve mathematical problems during the day, responses included:

- Teamwork

- Perseverance

- Patience

- Asking for help

- Confidence

- Your growth zone

- Breaking up the question

- Read the question carefully

- Don’t give up straight away

- Trial and error

- Stop and think

- Count to 10

- Discussing worries/strategies

- Writing down calculations

- Having fun!

The students appeared to leave tired but happy, taking away with them the strategies used in each of the activities and a laminated growth zone model!

Further exploration

If you want to find out more about Clare’s work with Sue Johnston-Wilder on mathematical resilience, you can visit their website here: http://www.mathematicalresilience.org/.

When I saw this oak leaf ribbon, I had to buy some – just because of its beautiful symmetry.

When I saw this oak leaf ribbon, I had to buy some – just because of its beautiful symmetry.