This is the third in a series of blog posts looking back at the history of the Department of Classical Studies at the Open University, on the occasion of the OU’s 50th anniversary. Janet Huskinson arrived at the OU in 1993, joining Lorna Hardwick and Chris Emlyn-Jones in the Department of Classical Studies.

Happy birthday, OU!

Many congratulations on being 50, which – I think it’s true to say – in human experience is a time for a big gulp, and a fair amount of self-reflection!

In fact, I was nearly 50 when the OU gave me my first, full-time permanent job, after many years of juggling various part-time jobs teaching Roman art in Cambridge (where I continued to live with my daughters).

So I know that a 50th anniversary is a good time for moving forward into a new future, while being aware of what’s been achieved in, and shaped by, the past. Many students speak from their heart about how their OU studies have led them to a new life. Well, I am an academic, a teacher, who can proudly say the same! It was a wonderful opportunity in so many ways.

Lorna Hardwick and Chris Emlyn-Jones have described in their blogs the early days of our Department of Classical Studies, and the many challenges and opportunities which it involved. Many years after it began, I joined them as a third colleague in 1993 – very soon to be followed by Paula James, another Romanist. As was the case then for colleagues in many university Classics departments, I found myself the only person whose specialism was not in textual but in material sources (in my case, visual). But here too, as the department expanded, I was soon joined by colleagues – Phil Perkins, Lisa Nevett, Val Hope, and Dominic Montserrat – with their own particular interests in the material culture of antiquity. (And now, one of the few things that just might make me regret retirement are the exciting new research opportunities offered by The Baron Thyssen Centre for the Study of Ancient Material Religion.)

Working with a variety of scholarly disciplines makes Classics such a good subject to study. But I think that the particular inter-disciplinary approach of our courses is a great strength – and not just for our students. Through teaching on OU course teams I’ve learned some lasting lessons , e.g. about working with various types of source material, and how to frame discussions at different levels, in terms that are informative, challenging and accessible. I’ve been able to apply them in my own research (on the visual imagery on Roman sarcophagi), but their impact was stronger on my teaching – perhaps because at the OU this also involved a variety of modern teaching media, rather than conventional lecturing.

I’ll just mention two courses, in which I was heavily involved during production (and for several years after in presentation).

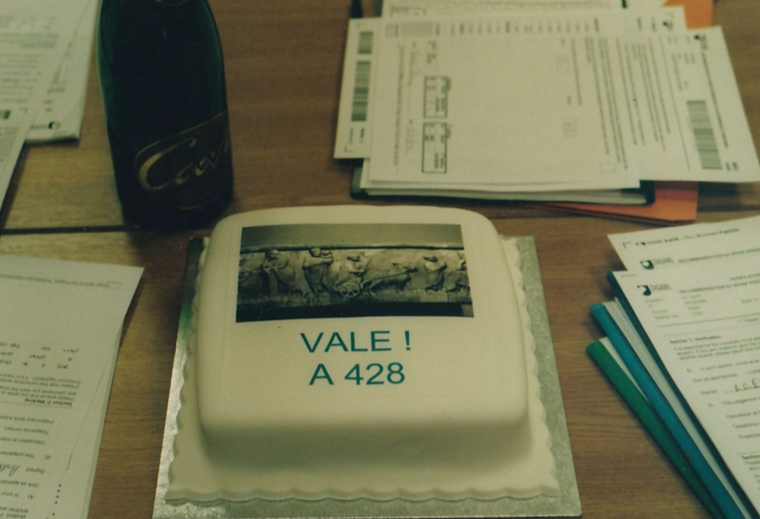

The first was ‘ A428 The Roman Family’, which I wrote with Paula. It was the departmental offering in a suite of short, low cost, low population third level courses which had a dissertation rather than an exam. as the final assessment. This was a fairly hot topic in Roman social history in the 1990s, and had inspired a number of books ideal as texts for our third level students (some of whom would have no prior knowledge of Roman society). I’d worked on it myself in the course of researching the imagery Romans used on children’s sarcophagi. So – for once! – I felt generally confident in my knowledge of the topic and ability to produce the teaching material required.

Sadly for me, the cost constraints in producing the material for these courses meant that I could not include many enticing illustrations of Roman art ( but by then I had already learned that I had unfortunately chosen an academic specialism that could prove expensive to write about, in teaching and research!) But the sources that were included, and introduced to students, were wide-ranging – as indeed were the subjects chosen by students for their dissertation.

This business of choosing subjects, and advising students on how to follow them through in writing up , helped make A428 a friendly and enjoyable course to teach. Students, tutors, and course team could get to know each other quite well in the process, which for me was great ( as I never quite reconciled to the OU’s lack of opportunity to watch students develop by teaching them face to face over a period of time). I was sorry when A428 ended – and I’ll now confess it was my favourite course to work on!

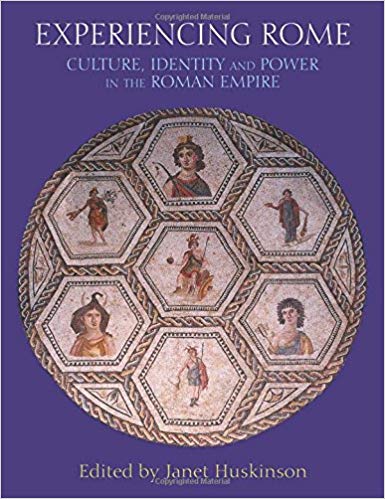

The second course , ‘AA309: Culture, identity and power in the Roman empire’, was in all respects, very heavy duty – certainly in comparison with A428, and my role as course chair there. This was to be the department’s principal Roman offering, and a successor to the much-loved course ‘Rome in the Augustan Age’. No pressure, then!

But we began with an excellent subject (chosen by Lorna, I believe), which linked into topical concerns in questions of identity, and in the ‘cultural turn’ of classical scholarship; and on the course team we had a strong range of talents and specialisms which would mean that we could teach interestingly about it for our students.

And we did, I think. The course attracted good numbers, and its book, Experiencing Rome (another good title, this time thanks to Paula), co-published with Routledge, was a great success on the open market and used as a textbook elsewhere.

En route to that happy ending I learned a lot – much about the opportunities of interdisciplinarity, but even more perhaps of the ‘keep calm and carry on’ type!

As for every OU course produced, I guess, there was the early problem of how best to structure the course so that it would deliver appropriate academic content (i.e. appropriate to the range of the Roman empire itself, to the range of historical sources to be taught, and to the range of students, some of whom may not have done a Classical Studies course before, and certainly not at third level) AND at the same time fit it with the expertise and personal timetables ( scheduled leave, end of contracts etc etc) of the course team members best suited to teach the various components. In the end many of us ended up writing about topics which wouldn’t have been our first choice, as I personally recalled rather bitterly when walking around forts on Hadrian’s Wall in a very wet July for a video on Roman Britain !

Interviewing Lindsay Allason-Jones at the the site of the Roman fort at Benwell, for the course AA309: Culture, identity and power in the Roman empire

At this time audio-visual material was still produced by the BBC unit at Walton Hall, rather than being contracted out to independent production companies. Picture research and the editing of our draft texts were done by specialists in the Faculty – so we got to know these colleagues well, for their support as well as for their regular issuing of deadlines. Looking back, I feel that we worked with a lot of paperwork, of which some items – usually some complex list of illustrations/captions – regularly went AWOL and had to be re-done in a hurry! But perhaps that’s just a fake memory. I do, however, have a lasting souvenir of some of our best (?) AA309 experiences – a ‘Candid Camera’ video sneakily made by Mags Noble our BBC producer of various course team presenters caught at unsuspecting moments. Not available for this blog, though!

Janet Huskinson ( OU 1993-2008)

April 2019