The Open University has offered some form of design education since it started in the 1970s, all based on pioneering work carried out by members of the OU by the Design Group.

You can read more about and watch the 50 year anniversary discussion events on the Desig@50 event page.

Foundation and Early Years: 1969 – 1975

The Open University was established in 1969, based originally on an idea of being a ‘University of the Air’ using broadcasting media to reach mature students at home. The original plans for the academic structure of the Open University were that it should be based on small units called ‘disciplines’, rather than conventional university departments, presenting courses through BBC television and radio broadcasts and printed texts.

The Design Discipline was founded as part of the University’s new Faculty of Technology (now Faculty of Maths, Computing & Technology) in 1970. The Faculty was the brainchild of Professor Geoff Holister, its first Dean, and it was due to his vision for a new, wider approach to technology education that the subject of Design was included. He appointed the first Professor of Design, John Chris Jones, who had previously been running the innovatory Design Research Laboratory at the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology. At the time of his appointment, Professor Jones had just completed his seminal textbook, Design Methods: Seeds of Human Futures.

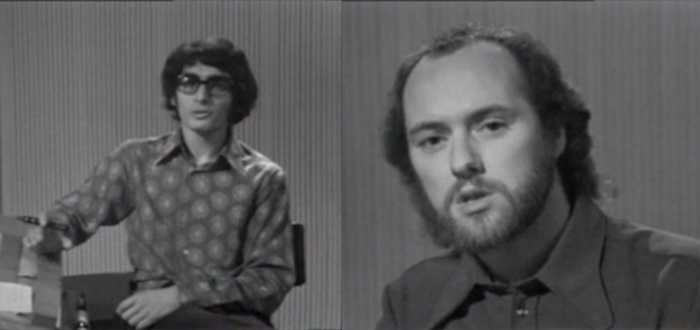

Figure 2 – Nigel Cross explains his analogy of the design process as a game of two halves in a BBC-OU TV programme recorded at the Alexandra Palace studios in 1975

Professor Jones’ first recruits to the Design Discipline were Chris Crickmay, Nigel Cross, Simon Nicholson and Robin Roy. Their first teaching contributions were to the Faculty’s Foundation Course in Technology, The Man-Made World, which began its first presentation in 1972. From the beginning, Chris Jones encountered difficulties in matching his vision for new forms of multi-media education with the early, rather restricted set of options that had been quickly developed for the Open University. However, he and his team did manage to introduce some innovations, such as loose-leaf collages of text materials, the use of audiocassettes, radio phone-in tutorials, and the students making their own video productions (using the newly available Sony reel-to-reel video recorders) at summer schools.

Eventually, the difficulties and frustrations became too much for Chris Jones, and in 1974 he resigned. The other Design Discipline members had already begun production of the first Design courses. Nigel Cross and Robin Roy (with Dave Elliott who had joined from within the Technology Faculty) produced the second-level course, Man-Made Futures: Design and Technology for first presentation in 1975. Simon Nicholson and Chris Crickmay produced Art and Environment for first presentation in 1976. Both of these courses were, of necessity, innovatory, and subsequently influential in UK design education.

Open University television programmes at this time were produced at the BBC’s original studios in Alexandra Palace, London. A lingering image of those early programmes is of academic presenters in tight suits and kipper ties; of course, the Design academics were more stylish than that.

A Developing Discipline Turns up the Heat: 1976 – 1988

A search had been underway for a new Professor of Design, and eventually Lionel March was appointed in 1976. Professor March was then at Waterloo University in Canada, but previously had been at Cambridge University Department of Architecture. There followed a period of expansion in Discipline membership, with Lionel March recruiting Philip Steadman, George Stiny and Ray Matela. Professor March also introduced a strong emphasis on research. However, in 1980 he resigned, to take up appointment as Rector at the Royal College of Art. Like Chris Jones, he had been unable to get to grips with the new teaching methods of the Open University.

Figure 3 – ‘Technology and Society’ one of the blocks in the course Man Made Futures, a second level course from 1975

Unfortunately, at this time the Open University was going through one of its occasional financial crises, and there was a freeze on making new appointments. (The outcomes of the first two appointments of Professor of Design might also have been influential.) The Design Discipline therefore remained without a Professor through most of the 1980s, with Nigel Cross appointed as Head of the Discipline. Eventually, external funding from Lucas Industries led to the appointment of a Professor of Engineering Design, George Rzevski, in 1988, and in the same year Nigel Cross was promoted to a personal Chair in Design Studies.

As before, amidst uncertainty at the top, other members of the Discipline got on with their research and with producing new courses. Some members of the Discipline had been influential in setting up an Alternative Technology Group (later the Energy and Environment Research Unit) in the mid-1970s, and Robin Roy founded the Design Innovation Group in 1979. Philip Steadman headed a Centre for Configurational Studies. There was now a very active research culture in the Discipline. Research and teaching have often interacted in the preparation of new course materials.

Figure 4 – Evaluating the Sinclair C5: A Design summer school at the University of East Anglia in 1986

Following the original ethos of the Faculty, and in tune with questioning the implications of conventional technological development, a new third-level, design-based course called Control of Technology was launched in 1978, and some of the discipline were influential in the new version of the Faculty’s Technology Foundation Course, Living With Technology, launched in 1980. A new course in Design: Processes and Products replaced Man-Made Futures in 1983. A third-level course in Design and Innovation was introduced in 1986, and Computer Aided Design was launched in 1987. Typical student numbers for these courses were around 300 – 500 per annum (with 6000 per annum on the Technology Foundation Course). Members of the Discipline also contributed to courses across the University, for example in the Arts, Mathematics and Social Sciences Faculties and the Business School

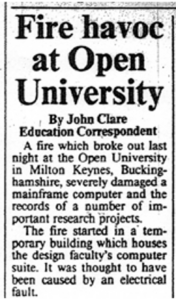

Figure 5 – A segment of the original article from the front page of the Times describing a fire in the department in 1987.

For twenty years the Design Discipline was housed in ‘temporary’ accommodation on the Open University campus – in wooden buildings known as Wimpey huts. On a Sunday afternoon in 1987, a mysterious fire broke out in the Discipline’s hut, Wimpey 3. The fire was reported in The Times and although the mainframe VAX computer room was burnt to the ground most of the offices escaped with just smoke damage. Amazingly, all the data were recaptured from the badly damaged computer, and the Discipline celebrated with a fire damage party, with music by the newly formed in-house lounge-rock group Wimpey Three. The group’s set list included versions of classics such as ‘Smoke Gets in My Eyes’ and ‘Light That Fire’ – a reworking of The Doors song, hinting at various explanations for the origin of the fire.

Sustaining the Future: 1989 – 2007

The 1990s saw a greater interest in design throughout society, with corresponding increases in the number of students taking Design Discipline courses. Professor Rzevski led the production of a course in Mechatronics: Designing Intelligent Machines, first presented in 1994. Two new courses appeared in 1996: a third-level course in Innovation: Design, Environment and Strategy, and a second-level course in Renewable Energy. The same year saw the launch of a new version of the second-level course Design: Principles and Practice, which had over 1000 students enrolled.

The 1990s also saw the Design Discipline included for the first time in the national University Research Assessment Exercises. Entering in the Art and Design subject category, the Discipline did extremely well, reaching the highest-grade assessment level in all three of the exercises, 1992, 1996, and 2001.

In 1997, recognising that the original idea of a ‘Design Discipline’ no longer reflected the reality of its expansion both in size and in range of interests, the Faculty and the University agreed that the name should be changed to the Department of Design and Innovation.

The start of the new millennium saw more growth in the Department, including the return from Newcastle University of Chris Earl, who had been a PhD student with Lionel March, as Professor of Engineering Product Design. Greater diversity was being introduced in the teaching patterns of the University, and Department members responded with new, shorter courses being offered at the Faculty’s first level in subjects such as Design and the Web, and Technology for a Sustainable Future. Some of the new courses were presented online, and all courses started to include computer-based elements, media such as DVD and other multimedia resources. The Open University was evolving from a ‘University of the Air’ to a ‘University of the Internet’.

Reconfiguration: 2007 -2016

In October 2007 a major University restructuring resulted in the creation of a new Faculty of Mathematics, Computing and Technology, with a merger of departments. As part of this, the Department of Design and Innovation was incorporated into the new Department of Design, Development, Environment and Materials. Design remains a strong focus within this new Department and is a recognised grouping. The Department of Design and Innovation has now (from October 2007) become The Design Group.

The publication of the UK Research Assessment Exercise in December 2008 was a major triumph for design research at the Open University. We were ranked third out of the 71 Art and Design submissions made. Our research quality profile was assessed as being 35% ‘world leading’ (4*), 45% ‘internationally excellent’ (3*), 10% ‘internationally recognised’ (2*) and 10% ‘nationally recognised’ (1*). This profile, as well as placing us among the UK’s top three design research groups was also the highest rating of all the Open University’s RAE submissions.

At the same time, the production of new modules continued and the strong research base gave greater confidence to the Design Group in the creation of new courses. This all came to fruition with the production and release of the pioneering course U101: Design Thinking.

2010- 2015: Design thinking comes (and goes…)

U101: Design Thinking was one of the major turning points in design education at the OU and, arguably, in distance design education itself. For the first time, a design course made use of the fundamental principles of the early design methods and studies movements to create a course in design thinking. The team also made use of the experience and legacy of teaching design at the OU. Led by Professor Peter Lloyd, the writing team included Nigel Cross, Emma Dewberry, Nicole Lotz, and was supported by other experienced and well-known team members.

U101 made use(then) emerging web 2.0 technologies, recognising that online creators and contributors represented forms of design thinking themselves. It developed several new learning technologies, including OpenDesignStudio (an online, virtual studio for students to share work), and CompendiumDS (a whiteboarding application and predecessor of Miro!). These technologies all allowed aspects of a student’s design process to be made visible, giving studente the opportunity to explain their thinking in designerly ways and to allow tutors to feedback to students more effectively on the process of design.

To this day, U101 is still used as an exemplar course that demonstrates effective Blended Learning, where the materials are carefully designed to offer exactly the ‘right sorts of experiences’ to students in supporting their learning.

What U101: Design Thinking was not, however, was the popular vision of design as a diagram of a process with lots of post-it notes on a wall. The richness of design methods and cognition that underpinned U101 is often rarely reflected in many contemporary design thinking models. This often leaves some of these as quite superficial treatments of design as a practice, whereas the vision of design at the OU is of a practice carried out by expert practitioners, whose expertise is neither generalised or specialised.

2016 – : Completing the project

In many ways, the success of design education at the OU lay in its ability to cross disciplines and appeal to students from many different backgrounds. The list of subjects OU design courses contributed to continued to grow and creative- and practitioner-oriented courses are still highly valued. For many OU students, being able to express themselves creatively, or to find alternative ways to demonstrate knowledge, or to simply respond to a personal development challenge, are all outcomes they find in studying at design at a distance.

Looking back at its history, it has been argued that the difficulties in teaching design at a distance are what make it work so well – you cannot teach design at a distance with half-considered materials or poorly thought through student experiences. During the pandemic, the Design Group came across this very challenge as they assisted colleagues in other institutions in developing their own distance design responses. It turns out that, just as in traditional design studio teaching, there is a lot of implicit practice when teaching at a distance!

However, whilst design was contributing to many other pathways and trans-disciplinary topic areas, it meant that the University still did not offer a full design degree in itself. Student feedback and research showed that there was a huge appetite for a so-called ‘design-design’ pathway in the Design and Innovation qualification. And developing this disciplinary specific curriculum also reflected Design Group members’ interests.

So, in 2016, work began to produce a full set of design courses that would contribute to a new design qualification – the Bachelor of Design (the BDes).

This work made use of the strong foundations laid in previous courses, scholarship, and research and builds on this by bringing it up to date with the latest research in design pedagogy. For the first time, the early theory in design, the experience of teaching design, and the scholarship and knowledge of how students become designers, all came together to provide a coherent understanding of distance design education.

The new BDes incorporates some of the original core ideas and theories created by the early work of the Design Group:

- Design can be practised and developed by anyone, not just a select(ed) few

- Design can be learned by treating studio (where we design) as a much broader idea, not just a single, privileged space

- Design relies on broader cognitive, practical, and reflective approaches and competencies, not simply a set of narrow skills

It only took 50 years!

Today, the OU Design Group continues this legacy of teaching design at a distance and making use of our experience and history to deliver high quality learning experiences. Our latest module started in October 2024, T190: Design practices, and this still builds on design methods and ideas generated over 50 years ago.