Lucy Rodriguez Leon is a lecturer in Early Childhood at the Open University

At time of writing, we’re several months into the Covid-19 crisis and the ‘second wave’ is gathering speed; on a personal level, the longevity of the situation is beginning to sink in. Children’s worlds continue to be disrupted in ways we could not have imagined at the beginning of the year.

At time of writing, we’re several months into the Covid-19 crisis and the ‘second wave’ is gathering speed; on a personal level, the longevity of the situation is beginning to sink in. Children’s worlds continue to be disrupted in ways we could not have imagined at the beginning of the year.

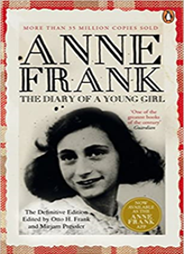

In the past, young people’s accounts of significant world events have offered unique insights that will never be found in history books or political rhetoric, such as the Diaries of Anne Frank. However, today children and young people have a range of media platforms that operate on a spectrum of private to public. I often wonder what Anne would have written had she known her paper diaries would be published for a global audience of millions, or had she had access to instant messaging or a blog.

ISBN-13: 978-0241952436 (Penguin)

Over the last few months many researchers have developed some creative approaches to capture and record children’s subjective realities of the pandemic as they emerge. My inbox and social media feeds have received a steady stream of information about covid-19 response projects. These include academic research into a range of educational and social issues using various methodologies. Community facing projects have aimed to collate children’s diary entries (consensually) to eventually publish an anthology as a record of this historic event. Other projects have consulted with children on how particular Covid issues affect them. Yet, I am still grappling with how this research can be genuinely participatory and authentically capture children’s perspectives on the issues that actually matter to them. Moreover, how can we do this ethically?

These projects face all the ethical challenges of any research with children; access, gatekeepers, fully informed consent, protection from exploitation or harm and accessible methods, for example. Some projects address these ethical and safeguarding challenges through insisting on parental involvement and mediation. Yet, arguably, participatory research requires trusting relationships to be forged and nurtured between researchers and participants, it requires dialogue, time for reflection, co-construction of ideas and thinking, collaboration – it is a process built on social interaction and connection, at a time that we are practicing social distancing. Of course, the affordances of digital technology have, to some extent, overcome the social distancing challenges.

However, the most concerning ethical dilemma, in my view, is researchers’ ability to respond to the issues that young participants might raise. In some respects, there has been great camaraderie and community positivity during the pandemic (think ‘Captain Tom’, rainbows and the ‘Clap for Carers’), but equally there are reports of children feeling isolated or going hungry, there have been escalations of domestic violence and unprecedented job losses, all taking their toll on children’s wellbeing. Furthermore, the nature of a global pandemic means that too many of our young citizens are living through bereavement.

There is undoubtedly a rich opportunity to capture children and young peoples’ perspectives of the pandemic, yet I’m curious about how researchers are honouring their ethical responsibilities. Firstly, how can we ensure that research offers a supportive space for participants to explore, discuss, express, connect and make sense of the ongoing and evolving situation. Secondly, in what ways will all children’s voices be authentically represented in research or in any resultant anthologies, particularly if parent or teacher mediated? Is there a danger that some voices are being heard, whilst others are being marginalised?

Dr Lucy Rodriguez Leon is a Lecturer in Early Childhood at the Open University and co-convenor of the UKLA Early Years Special Interest Group

Dr Lucy Rodriguez Leon is a Lecturer in Early Childhood at the Open University and co-convenor of the UKLA Early Years Special Interest Group

During the lockdown, increased online communication made it clear that social media are a key place to stay in touch with the world around us. With their persuasive marketing techniques, Facebook, Instagram or Twitter’s algorithms are designed for exponential growth and not for deep conversations. They are designed for amplifying content that is typically the most controversial, latest or shocking news. And yet, social media are also the place where professionals share useful resources and academics exchange latest research papers. For millions of users, social media are the place where they begin and end their daily interactions. So, whether you hate them or love them, you probably realize that you should be part of at least one social media platform. But what if you are one of the digital introverts whose heartbeat goes up even by receiving a group email? What if you prefer alone time rather than the mega social conversation?

During the lockdown, increased online communication made it clear that social media are a key place to stay in touch with the world around us. With their persuasive marketing techniques, Facebook, Instagram or Twitter’s algorithms are designed for exponential growth and not for deep conversations. They are designed for amplifying content that is typically the most controversial, latest or shocking news. And yet, social media are also the place where professionals share useful resources and academics exchange latest research papers. For millions of users, social media are the place where they begin and end their daily interactions. So, whether you hate them or love them, you probably realize that you should be part of at least one social media platform. But what if you are one of the digital introverts whose heartbeat goes up even by receiving a group email? What if you prefer alone time rather than the mega social conversation?