Post 7 Petrarch in Love

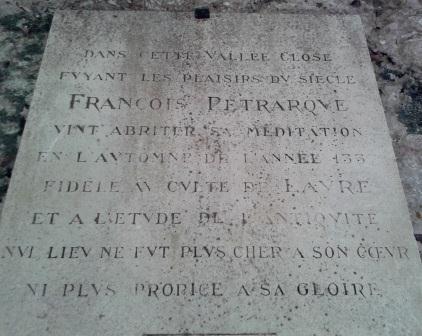

Once again, off in pursuit of Petrarch. This time, not to Italy but the south of France. Petrarch got about a fair bit – born in Arezzo, mostly brought up in Avignon, studying in Montpellier and feted in many courts across Europe, including Paris and Rome. In many of these places he is celebrated with plaques, but the two places most associated with him are the house in which he died, in the Eugaean Hills above Padua, and Fontaine-de-Vaucluse in Provence. The Petrarch who is celebrated in these two places however, though historically the same person, is very differently imagined. One is ‘French’, one ‘Italian’. He identified himself as a Florentine, apparently out of intellectual snobbery, because his family was native to that city, expelled in the same political purge that sent Dante on his wanderings. The plaque above, put up in the village of Vaucluse, lays claim to Petrarch in French because ‘nul lieu ne fut plus cher a son Coeur/ni plus propice a sa gloire’, that is to say ‘no place was closer to his heart, nor more suitable to [the celebration of] his fame.’ That’s one in the eye for Arqua-Petrarca.

Fontaine-de-Vaucluse is not easy to get to, and that was largely the point of it for Petrarch, fleeing, as the plaque above puts it, from worldly pleasures. As the name suggests, it is a village in a dead-end valley, closed at the further end by an enormous limestone cliff. At its foot, out of its mostly unmapped, immeasurable, underground cave-system, rises the river Sorgue. The green swirling pool under the cliff which is the fontaine itself was long reputed fathomless. When the water-level is high the water pours in a huge white stream across boulders down through the valley, joined by streams from both sides that also spring from the cliff. The wonder is the water, as clear as glass, almost a platonic description of water, bright green over the waving weeds, a brilliant turquoise where the flow has been violent enough to scour the weed away in underwater pools to leave only white sand. The place had been a wonder well before Petrarch ever set eyes on it.

Today we drive up one side of the river in a rental car. In the nineteenth century the roads were rough enough and the place so remote to deter even the intrepid traveller Marianne Colston from lugging her young baby along on the expedition – and she had baptised her daughter at the inn on the Simplon pass in the Alps in winter. Like Colston, we’re in search of Petrarch’s famous retreat. Here he took a small house, made a garden, amassed a large and remarkable collection of books, and devoted himself to a life of literary retirement and cultivation of the mind. Here, according to his many letters that describe, meditate and mediate this project, he conceived and executed much of his enormous literary and intellectual output. Even in his lifetime, he could plausibly claim that though the Fontaine had been celebrated as a natural wonder before he chose it as his home, his residence had vastly increased its celebrity. By 1525, early books containing drawings and maps of Vaucluse are already identifying Petrarch’s house – this was roughly the date when those Austrian students were carving their names in the mantelpiece in Petrarch’s house in Arqua. But whereas the Petrarch celebrated in Arqua is the man of the Italian Renaissance, in Vaucluse Petrarch appears as emphatically French, and the prototype of the Renaissance lover. This is probably a nineteenth-century formulation, born of nationalism, and in particular of the division of what we know as Italy between Napoleon’s France, the king of Rome, and later Austria.

At the centre of the village of Vaucluse, bustling this morning with a market and long crocodiles of school-children, there stands a neo-classical column. This is the column Napoleon put up in 1804 to commemorate the five hundredth anniversary of Petrarch’s birth. Not only did this make Petrarch into an honorary Frenchman, it put the Napoleonic seal of approval on him. Napoleon was a great one for commemoration as befitted a child of a revolution that had to invent a state and its rituals from scratch – he regularly visited sentimental literary locations, and this was one of the most important of them for contemporaries. The column wasn’t originally placed here; with an imperial sense of importance, Napoleon caused it to be placed in the mouth of the cavern, where it seemed so unsuitably phallic and otiose that continual protest eventually resulted in its re-siting in 1827.

Why celebrate Petrarch’s birth here? One reason is the fame of Petrarch’s Canzoniere, a cycle of 750 love-poems addressed to an unidentified married woman, ‘Laura’, both in her lifetime and after her death. Petrarch met Laura, according to these poems, in Vaulcuse, and they made Vaucluse into an emotional geography of modern love. Another reason was that Petrarch himself identified the source of his poetic inspiration with the river-source, so that Vaucluse could be celebrated as the place of the birth of his genius. But Petrarch achieved an additional, special importance in the early nineteenth century because he accidentally became a romantic revolutionary in the mould of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose works, especially his sentimental fiction and autobiographical writings, presided over the French Revolution His extensively autobiographical letters, his obsessive love for a married woman, and his evocation of this particularly beautiful and exceptional watery landscape as the ground of both love and genius – all serendipitously doubled the romantic enthusiasm elicited by Rousseau’s autobiographical writings Confessions and Rêveries of a Solitary Walker together with his novel Julie: ou, La Nouvelle Helöise for associated landscapes. Petrarch under the pressure of this analogue was promoted to a quintessentially romantic subjectivity, and the place became a suitably romantic location even though Petrarch’s house and garden had long vanished, and even the house pointed out to eighteenth-century travellers such as Casanova was at some juncture destroyed. What Petrarch had conceived as Virgilian retreat was now reinscribed as a Rousseaustic retreat into the wonders of nature; and Petrarch’s European wanderings now seemed analogous to Rousseau’s successive exiles. Tourists went to marvel at the pool, imagine Petrarch walking there, imagine the moment at which he imagined the apparition of Laura there, and to express this experiment in subjectivity through composing and leaving their own signatures, inscriptions, and effusions.

Today Vaucluse is so full of people avoiding the heat of the plain that it scarcely feels much of a retreat. The left-hand bank of the river Sorgue is devoted to the sort of tourist stalls that spring up around a natural wonder – olive bowls, lavender soap, thin white shirts, 3D postcards of ginger kittens superimposed on a picture of the Fontaine and sending ‘gros bisous’ to prospective recipients, ‘glaces’ in neon colours, a spelunking museum, a traditional paper mill. The river is hung with batons for white water canoeing, and out over its now concreted banks decks with bars and cafes have been built. Petrarch seems pretty invisible here, but, past all these delights, and walking on up to the source, you come to a rock wall with three plaques celebrating Petrarch, one in Italian, one in French (see above), and one in Esperanto in barely veiled competition. On the right hand side of the river, all is more Petrarchan. Beneath the ruined chateau and through a rock tunnel sits the Musée Petrarch, conjecturally on the site of the original house and garden. Set up in first in 1927 and reopened in 1986, it contains a spectacular collection of books and prints chronicling the history of Petrarch’s reputation – successive representations of him, or Laura, and of the locality.

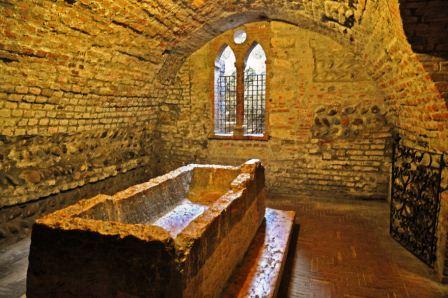

At Arquà, the cult of Petrarch references Laura through the sixteenth-century frescoes commissioned by an admirer, which show, for example, his discovery of the bathing Laura. But, on the whole, Laura is eclipsed there by the story of Petrarch’s death at his desk which is reified in Petrarch’s vast tomb sited just down the hill. At Vaucluse, the important tomb has always been that of Laura. The existence and identity of Laura herself has often been contested; so too the whereabouts of her tomb. In the early nineteenth century, it was being shown in a monastery in Avignon. Much earlier, though, Francis I deemed it politically desirable to play up the fact that Petrarch had been in love with a French woman, and commissioned a search to find her tomb. The courtier charged with the task prudently ‘found’ a tomb and its occupant was duly exhumed. A young woman’s skeleton was discovered, accompanied by a small metal box containing a scrap of parchment bearing a set of initials which could be, and very naturally were, construed as Laura’s; Laura’s tomb was declared discovered, and Francis himself was said to have taken his mistress along on a jaunt to pay his respects.

Perhaps even more telling than juxtaposing these two tombs is to counterpose the representations and celebrations of Petrarch’s two supposed lovers, his cat and Laura. I’ve already written a bit about Petrarch’s cat in a previous post – here is a tongue-in-cheek translation made by my daughter of the Latin inscription supposedly spoken by the cat that appears beneath its displayed body:

‘The Etruscan poet burned with double love;

I was his greatest flame, Laura came after;

And now, I wonder, what provokes your laughter?

If she was granted beauty from above,

She makes me, by compare, the faithful one;

If little books she inspired

For my part I ate mice just as required

And kept them from the sacred bounds beyond

So my great master never was distracted

Or startled by those squeaking bold incursions.

And, although dead, I still perform my duty.’

Thus runs the epitaph we love redacted

On Petrarch’s cat – and do not cast aspersions.

For thus we see, mouse-catching excels mere beauty.

Both cat and Laura inhabited real bodies even if they have only conjectural reality. The celebration of Petrarch’s cat valorises the Italian over the French, domestic management over illicit obsession, the old Petrarch over the young, the bookish over the lyric, the study over the source. One might then juxtapose the cat with the astonishing evocation of Laura (above) that looms in the middle of the house at Vaucluse. Headless, vastly elongated, it represents a woman’s body with two backs – one clothed in bridal white, one in funereal black.

The cult of Petrarch’s houses is so long-lasting and begins so early that it seems to pose a serious challenge to the otherwise tenable hypothesis that imagining the author on or through location is essentially a romantic matter, and a matter, very often of romantic nationalism. It rouses the question of what the distinction is between the author Petrarch as he is imagined successively by the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Romantics and through to the present day. Was Petrarch was celebrated as a modern classic, as he himself imagined himself as the colleague and son of Virgil and Ovid, and did Vaucluse then become a French extension to the ‘classic ground’ of southern Italy? This is a research question for another day, because it would require a wholesale investigation and analysis of visits to Vaucluse before 1800 to determine what visitors were ‘in search of’, and what responses they were engaged in reiterating.

The cult of Petrarch’s houses is so long-lasting and begins so early that it seems to pose a serious challenge to the otherwise tenable hypothesis that imagining the author on or through location is essentially a romantic matter, and a matter, very often of romantic nationalism. It rouses the question of what the distinction is between the author Petrarch as he is imagined successively by the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Romantics and through to the present day. Was Petrarch was celebrated as a modern classic, as he himself imagined himself as the colleague and son of Virgil and Ovid, and did Vaucluse then become a French extension to the ‘classic ground’ of southern Italy? This is a research question for another day, because it would require a wholesale investigation and analysis of visits to Vaucluse before 1800 to determine what visitors were ‘in search of’, and what responses they were engaged in reiterating.