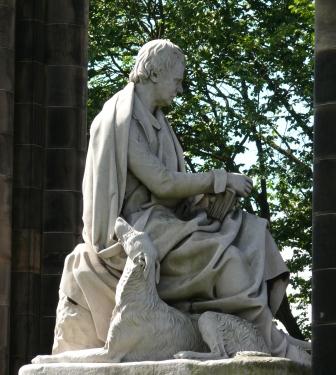

Last June, I went to Winchester Cathedral to marvel at their flower festival, and, as a scholar of Austen, to photograph the grave, brass plaque, and stained-glass window that between them memorialise her there. Plunging into a particularly excited and dense crowd down a side-aisle, I discovered Austen herself. And here she is.

In the two hundredth year of the publication of Pride and Prejudice, creating this large and lavish display was reserved by the Winchester Cathedral flower arrangers to themselves. It was located almost on top of Austen’s grave, in the centre of the aisle. Behind her gravestone, there is a late 19C brass plaque, put up by her nephew at the moment when Austen was first becoming a canonical novelist, in large part as a result of his Memoir of Jane Austen published in 1870. And above that, there is a memorial stained glass window, put up even later, in the early twentieth century. The display itself suggested at least two mendacious things: first, that ‘the English country garden’ in the late eighteenth century was full of peonies. Secondly, that Austen was in the habit of working in the garden on furniture that if it had been outside on this particular summer’s day would certainly have been ruined by torrential rain. But the installation had a sort of truth nonetheless – the ‘Englishness’, femininity, and controlled domestic compass of Austen’s fiction is congruent with this fiction of an idealised country garden, and the prevailing popular sense of Austen as a woman writer who composed within and about the confines of the domestic was convincingly staged. In fact, there is a long tradition in travel-cum-biographical writing of the ‘homes and haunts’ genre, stretching back to the early 1910s, of visiting Chawton Cottage and imagining Austen, imagining her characters, or imagining Austen looking out onto the garden and imagining her characters. The traditional English garden is often enough specified as Austen’s ground of inspiration, and as the best and most natural backdrop to her particular evocation of English society.

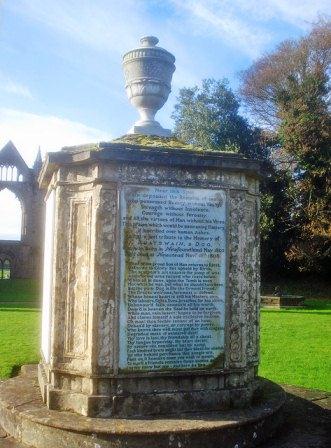

Within this frame, a number of other rather conventional things are re-stated about catching genius in the act of creative writing. The inclusion of a dummy Austen insists, for example, on the need to imagine and re-animate the volume of the writer’s body – here, with an unusually and unintentionally macabre literalism, actually rising above Austen’s bones. It insists on the importance of the writer’s hand, foregrounded carefully on the writing-table. It points to the indirection of the reader’s relation with the authorial body, which is only inferred or created by readers from the writing, by positioning the dummy in such a way that the writer’s back is turned away from the viewer, and the face is completely hidden. It details not only the embodiedness of the author but the materiality of the business of writing, assembling here its tools, the chair, desk, inkstand, quill-pen, and paper. Finally, it emphasises the moment at which writing comes into being, when the paper is almost blank, when the first famous sentence is written, but discarded by its originator, when the second attempt is about to be made. It is interested in the moment when a quotation is originated, before it knows and is known to be a quotation.

Of course, nothing in this tableau of the writer at her desk in the garden is ‘authentic’ — except the considerable amateur affect invested in it. The table, for instance, is not the famous twelve-sided walnut table in Chawton Cottage, on which Austen is said to have written. That said, it looks quite like it, which suggests that the Cathedral flower arrangers expected that at least some of the visitors would be familiar with what Austen’s table looks like, as familiar as they are with the opening of Pride and Prejudice. This is merely a representation of the writer’s desk and a fanciful one at that. But what it can tell us about ‘real’ writer’s desks is simple but important – it tells us that even the real thing is self-representational, and that what it must strive to represent is the writer at work. This is not as easy as it might sound at first. The writer’s desk (and the writing materials associated with it) are culturally required to describe something immaterial and invisible, and quite possibly entirely fictional – the supposed instant when something happened that has subsequently come, often by slow accretions, to certify the genius of a person and a place, and often the productive confluence of the two.

In microcosm, the problem of making the writer’s desk into the Writer’s Desk is a matter of what John Urry long ago in The Tourist Gaze called ‘site sacralization’. Even if you have the very table, it is only a table until it is provided with markers of signification and valuation, and framed within a narrative of the moment of creation. The production of this ‘aura’ (to borrow Baudrillard’s famous term) is what collectors, curators, and visitors all work at. It is one important way in which ‘genius,’ or rather the cultural fiction and functionality of genius, is produced through representation, performance, and reiteration.

It is therefore instructive to compare the Austen display in Winchester Cathedral with the permanent display in Chawton Cottage – not so much to draw out the differences between the floral fantasy and the real thing, but to get at the marked continuities between them.

This battered, undistinguished and rather rickety piece of Regency furniture is displayed in Chawton Cottage as Jane Austen’s writing-table. It certainly belonged to Chawton, was inherited by Austen’s sister Cassandra and bequeathed by her in 1845 to a manservant; thereafter it found its way back to the cottage when it was being set up as a heritage site in the 1920s. The table in Winchester Cathedral required gravestone, brass plaque, memorial window, a bonneted dummy, writing materials, and apparently discarded manuscript to stage it as ‘Austen’s table’. By comparison, the contemporary display of this table seems almost ostentatiously understated – a window, a chair, a table, an empty crystal inkstand and a single quill. This is partly possible because the house itself acts as narrative frame. Nevertheless, this table is, as in the floral display, clearly not just a table. It is ostentatiously not for further use. Protected behind a perspex screen, it is to be seen but not touched. Paradoxically, the very absence of the writer’s body fulfils the same role as the dummy seated on Austen’s grave – it represents the space of the writer’s originating body, while describing its vanishedness. The solitariness and domesticity of the act of writing in the garden staged in the cathedral is re-described here in terms of the quiet sitting-room, which comes with a famous story of the door with the creaking hinge that supposedly gave Austen enough warning to conceal her writing from all but her close intimates. The transparency of perspex produces on the one hand the value of the object through introducing distance and encouraging focussed meditation, and on the other hand, according to Anna Woodhouse, a readerly, fan-style, identity shaped by aspirational desire.[1] Genius-as-a-commodity is therefore produced by a negotiation between reader-tourist and curator around an object seen through a transparent barrier. Or one might speculate that the perspex functions to denote distance in multiple ways – the distance between use and celebrity value, between organic material and immaterial narrative, between material conditions of production and the miasma of reputation, between pieces of paper and the accolade of ‘genius’, between reader and author, and the ever-enlarging distance in time between reading and composition. Above all, it marks the distance of present-day consumer from long-dead genius.

All writer’s desks differently inflect this common description of genius. Yet some are more unusual than this would suggest, and this desk is one of them. There aren’t many women authors who have ever been designated geniuses, even in the nineteenth century which was particularly fond of the idea and the category. It’s a specialised and interesting category. One might think here, for example, of Germaine de Stael and George Sand. Fewer still have continued to be regarded as geniuses, but among their number we can (still) include Austen.[2] Austen’s writing-table at Chawton is very unusual among curated writer’s desks in that it bears hardly any marker to single it out. There is no claim to provenance, and few traces of ‘work’. No paper, no ink, no paper, no sand-sifter, no proofs, no personal belongings, no books, no candle, no brass plaque or inscription, just a single feather. This is a willed blankness. (There is a history to the display of this table, but I only have space here to describe how it appears nowadays.) Although it is probable that Austen sat at this table which was clearly never designed as a writing-table, her writing-desk was something else altogether – a handsome and expensive mahogany writing-box which opened into a slope and would have sat on the table itself. Gifted in 1999 by an heir, Joan Austen Leigh, to the British Library, it is now held in the Sir John Ritblat gallery, together with its contents, including Jane Austen’s eye-glasses and her sewing kit or ‘housewife’.[3] That, if anything, is the true paraphernalia of genius. But so far it has had little purchase on the representation of Austen in the act of writing. So what does this contrived blankness at Chawton say about how our culture imagines the nature of Austen’s ‘genius’?

The clue, I think, is the marginal, even opportunistic scene of writing that both the writing desk in the British Library and the table in Chawton Cottage in their own ways dramatise. At the opening of the Millennium exhibition at the British Library, Claire Tomalin, as biographer of Austen, said of the writing-desk that it demonstrated that ‘All you need if you are a writer is a desk, a pencil and of course a great brain.’[4] (Never mind that Austen did not write in pencil.) She had much the same to say about the table at Chawton, emphasising its smallness: ‘This fragile 12-sided piece of walnut on a single tripod must be the smallest table ever used by a writer…. Today, back in its old home, it speaks to every visitor of the modesty of genius.’[5] This sentiment – the sense that any woman could be a genius if Austen could be out of such supposedly modest conditions — can be verified by recourse to the blogosphere, well-populated by Austen enthusiasts. This is Cindy Jones, posting an account of her literary pilgrimage to all places associated with Austen in 2010:

Standing in the simple room where the modest writing-table occupied a spot near the window, I felt my Jane Austen’s presence. Not the celebrity icon, but the unaffected woman reined in by class, money, and gender. … Jane Austen was the person I had imagined: physically present at the little table, yet mentally far away, working in a universe of her own creation. And this is what we both understand: being stranded on a desert island is not a problem as long as you have paper, pen, and writing-table. Her writing-table is the most unassuming piece of furniture with the most impressive back-story I’ve ever met.[6]

If Jane Austen could do it, then so can we; and if immediate inspiration eludes us budding geniuses, we can always buy some scented drawer-liners and head over to the tea-shop, where they have invariably stopped serving tea five minutes ago.

[1] Anna Woodhouse, ‘How glass changes the way we see the world’ Four Thought Radio 4 29 May 2013, downloads.bbc.co.uk… fourthought_20130529-2059a.mp3

[2] Cf. Deirdre Shauna Lynch, ‘Jane Austen’s Genius’

[3] Freydis Jane Welland, ‘The History of Jane Austen’s Writing-Desk’, Persuasions 30.

[4] News, Views & Titbits republished from http://www.jasa.net.au/newsdc99.htm last accessed 19 June 2013

[5] Claire Tomalin, The Guardian Sat 12th July 2008 ‘Writer’s Rooms: Jane Austen’

[6] Cindysjones.wordpress.com/2010/08/24/i-met-jane-austens-writing-table last accessed 19 June 2013

A writer’s birthplace like that of Shakespeare’s is of course in some sense a ‘writer’s house’. But it is almost never the house in which the writing has actually been done, the workshop of genius. One house that does speak eloquently of the writer’s labour, however, is Abbotsford, the most famous of the many homes of Sir Walter Scott, poet, novelist, and a nineteenth century national treasure. Continue reading

A writer’s birthplace like that of Shakespeare’s is of course in some sense a ‘writer’s house’. But it is almost never the house in which the writing has actually been done, the workshop of genius. One house that does speak eloquently of the writer’s labour, however, is Abbotsford, the most famous of the many homes of Sir Walter Scott, poet, novelist, and a nineteenth century national treasure. Continue reading