I suppose what I have been exploring in this series of literary adventures is the impulse to experience for real places that one first found through books. Poets’ graves seem to offer a temporal and physical limit to the slightly unnerving experience that books can generate of intimacy with people long-dead, although they have very frequently been changed to look more like what you might expect if you had read the book. Writer’s birthplaces offer a similar experience of constraining the sense of the author’s presence within space and time, although they too have a tendency to change to match the mythos. Writer’s workshops begin by looking like something biographically accurate, specified to the actual desk and chair, but sometimes, as in the case of Hill Top and Hemingford Grey, begin to change into the very stuff of fantasy. Writers brand whole ‘countries’ by their ability to romance them repeatedly, until the country begins to change for real. What all this begins to suggest is a profound desire on the part of readers to visit worlds that are, and are not there, that are vivid in imagination, and yet frustratingly out of reach.

I suppose what I have been exploring in this series of literary adventures is the impulse to experience for real places that one first found through books. Poets’ graves seem to offer a temporal and physical limit to the slightly unnerving experience that books can generate of intimacy with people long-dead, although they have very frequently been changed to look more like what you might expect if you had read the book. Writer’s birthplaces offer a similar experience of constraining the sense of the author’s presence within space and time, although they too have a tendency to change to match the mythos. Writer’s workshops begin by looking like something biographically accurate, specified to the actual desk and chair, but sometimes, as in the case of Hill Top and Hemingford Grey, begin to change into the very stuff of fantasy. Writers brand whole ‘countries’ by their ability to romance them repeatedly, until the country begins to change for real. What all this begins to suggest is a profound desire on the part of readers to visit worlds that are, and are not there, that are vivid in imagination, and yet frustratingly out of reach.

In the trilogy His Dark Materials (1995-2000), together with the publication of a tailpiece postscript and supplement entitled Lyra’s Oxford (2003) and now the first part of a new trilogy The Book of Dust, La Belle Sauvage (2017), Philip Pullman constructs a parallel Oxford available only through the opening of ‘windows’ or ‘doorways’ between worlds culturally distinct but geographically equivalent. He juxtaposes an Oxford which we as readers recognise, and an Oxford which we only partially recognise: Will’s Oxford, and Lyra’s Oxford. Will effectively acts as tourist ‘guide’ to Lyra in his world, Lyra to Will in hers. His Dark Materials finishes with the deliberate and principled closing down of such windows, and the consequent parting of the now-lovers, Will and Lyra. This narrative provides commentary on the fiction-reading (and indeed fiction-writing) process. Even while the fictional world is described in documentary detail, it turns out that this is the documentation of a world that simply does not exist: or rather, one that exists purely for those absorbed in the fiction. With the windows between alternative worlds slammed shut, Will is offered one consolation: the practice of ‘double-seeing’ – that is, of witnessing both worlds at once, as in an optical picture. By suggesting that Will’s Oxford and Lyra’s Oxford are able to co-exist through the practice of ‘double-seeing’, Pullman essentially licenses literary tourism.

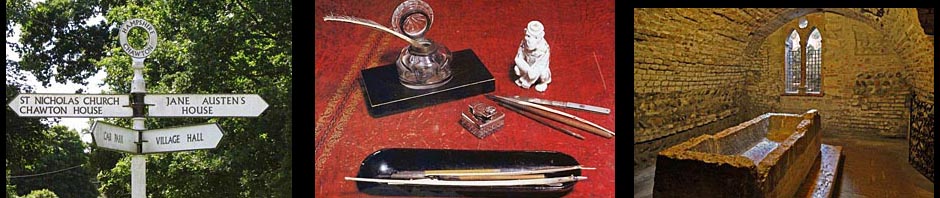

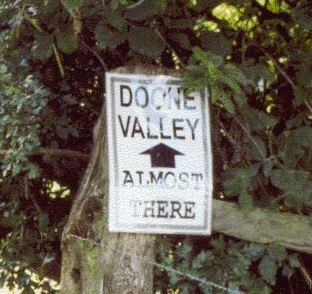

By 2003, with the publication of Lyra’s Oxford, a super-short book dealing with an adventure of Lyra’s supposed to post-date The Amber Spyglass (2000), the third novel in the Dark Materials trilogy, Pullman was already playing literary games with this idea. To promote the book at the Oxford Literary Festival in spring 2004, Pullman helped design a literary walk, for which I, naturally, bought a ticket. A remarkable experience, the walk began in Exeter College (the location and part-original with Christ Church for Lyra’s Jordan College) and wound its way via on-site readings down to the district of Jericho where the story reaches its climax, coming to rest in the little half-derelict St Sepulchre’s cemetery. This tourist activity was dictated by Lyra’s Oxford itself, which contains not merely a full map of ‘Lyra’s Oxford’, but a souvenir postcard, divided into four pictures, one showing the street-name sign ‘Norham Gardens’ where the scientist Mary Malone is supposed to live, one the hornbeam trees in Sunderland Avenue where Will finds his first window into another world, one the Science Buildings, and one the seat in the Edenic Botanic Gardens where Lyra and Will promise to keep tryst every Midsummer’s Day at midday.

The way to find this pictured bench had already been carefully specified in The Amber Spyglass:

She led him past a pool with a fountain under a wide-spreading tree, and then struck off to the left between beds of plants towards a huge many-trunked pine. There was a massive stone wall with a doorway in it, and in the further part of the garden the trees were younger and the planting less formal. Lyra led him almost to the end of the garden, over a little bridge, to a wooden seat under a spreading low-branched tree.

When I took my children with me to follow this itinerary and find a corresponding real bench in the summer of 2004, a hot argument ensued: the bench on one side of the bridge corresponded with Pullman’s postcard and map, but the bench on the other corresponded with that which had appeared in the National Theatre’s spectacular dramatisation of the trilogy that winter. On this occasion, the children won the argument. But if you go to the Botanic Gardens these days, you’ll likely find a little bunch of flowers laid on the other bench, or someone with an inexplicably satisfied look photographing it. The tourists you will spot have come for a type of sentimental experience dating all the way back to the late eighteenth century: they have come in search of the forever-inaccessible Lyra. So powerful is the desire to find the secret window into another, fictional, world for real.

The problem, and the metaphor, of ‘Lyra’s bench’, then, returns the tourist to the text. It provides hard evidence of the absence of physical reality at the heart of the reading experience. This mixture of presence and absence that the fictional text creates constitutes both the charm and the embarrassment of literary tourism. Not content with the airy virtuality of fiction, we, as literary tourists, seek to found it upon biography, and real geographical landscape. We try to reanimate the hours of reading beyond the bounds of the book, welding literary memory into physical, bodily memory. Such tourism involves enacting the art of reading as the art of make-believe; it involves creeping through Pullmanesque windows and doorways, entering voluntarily into a waking dream that ceaselessly converts the fictive to the real and back again.