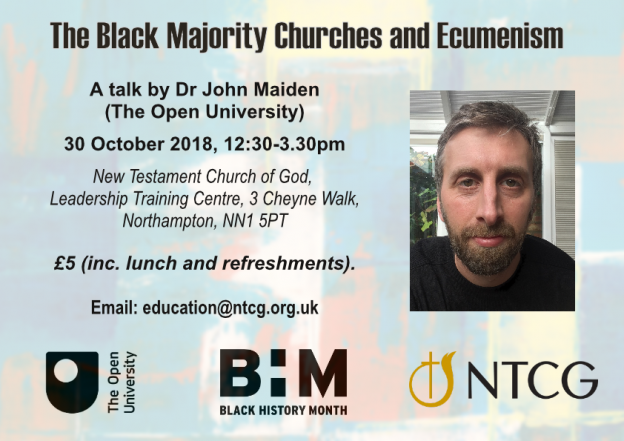

On 30 October as part of Black History Month the department is contributing to ‘The Black Majority Churches and Ecumenism’ [pdf flier here] – a public event at the New Testament Church of God Learning and Training Centre in Northampton. The event is hosted and chaired by the Revd. Phyllis Thompson of the NTCG. In the Q and A with Dr John Maiden below, Revd. Thompson discusses the history of relations between the historic mainline churches and the BMCs in Britain, and says more about this event.

How would you describe the interactions between local black majority churches and mainline congregations in Britain in the 1970s and before?

The interactions were tentative and fraught in the main due to ignorance, scepticism, disappointment, frustration, racism and rejection to mention a few of the reported experiences. Some of the men and women who came to the UK during this time, came as migrants and missionaries. Oliver Lyseight, for example, founding admin Bishop of the New Testament Church of God and listed 3rd of 100 Black British Achievers, belongs to a denomination which is part of a global Pentecostal movement currently with over 8 million members in over 34,000 local congregations in more than 184 countries around the world (www.churchofgod.org). Determined to sustain his faith in the midst of the dissatisfaction and discontent, Oliver Lyseight – like many others – established branch congregations of their Pentecostal denominations in the UK. Given the sociopolitical issues mentioned earlier, the so called ‘black majority churches’ emerged and with this history the critical need for meaningful and sincere dialogue to address the fears, prejudice, and injustice of racial discrimination and identify ways in which the ‘historic churches and the so called ‘black majority churches’ could dialogue and find a voice to bring healing amongst its constituency, and together present the Christian message to the wider community.

You were involved in a project called Zebra in North East London from the late 1970s. What was Zebra and what was its approach to developing local relationships between BMCs and mainlines?

The Zebra project, as Deryck Collingwood, Chairman of the London N. E. District of the Methodist Church, said at the time, ‘was born out of disappointment.’ Ira Brooks, a leading New Testament Church of God Minister speaking on behalf of the Zebra Project, said ‘I have watched the painful success of Zebra from inside – having worked as a member of its steering committee for some years… people from various walks of life and professions are becoming more and more aware of it as a resource of information and expertise, especially within the delicate and difficult matters of racial harmony that are available for the use of blending and strengthening Britain’s multi-faith/cultural society for the 21st century.’ Insightful dialogue with the aim to encourage and support people of different backgrounds to work together to bring about racial justice was central to the Zebra Project.

The public event on 30 October will explore some of this ecumenical history, and you will be chairing a discussion. How is this history, and the issues it raises, relevant to the churches in Britain today?

Clearly there is much to celebrate about the relationship between the ‘black majority churches’ and the ‘historic churches’ – this is evidenced, for example, by the make-up of the leadership and work of Churches Together in England.

However, there is still a great deal to be done. An understanding of and engagement with the historical context of the UK Churches should be a must for all church leaders who are keen to build on the wisdom of hindsight.

What do you think has been the impact of black majority churches on Christianity in Britain since Windrush?

The black majority Churches have made and continue to make significant contribution to the British religious landscape and the Christian witness in particular. Karen Gibson and her Kingdom Choir’s performance at the Royal wedding on the world’s stage is a good example, as are the many other Pentecostal Christians of African/Caribbean background who are making tremendous contribution via the so called seven spheres of influence as itemised by Loren Cunningham: Family, religion/church, Education, Government, Media, Celebration (Arts, Entertainment and Sports) and Economics(Business, Science, and technology).

The event costs £5, including lunch and refreshments. To book, email [email protected]