By Jeff Horner

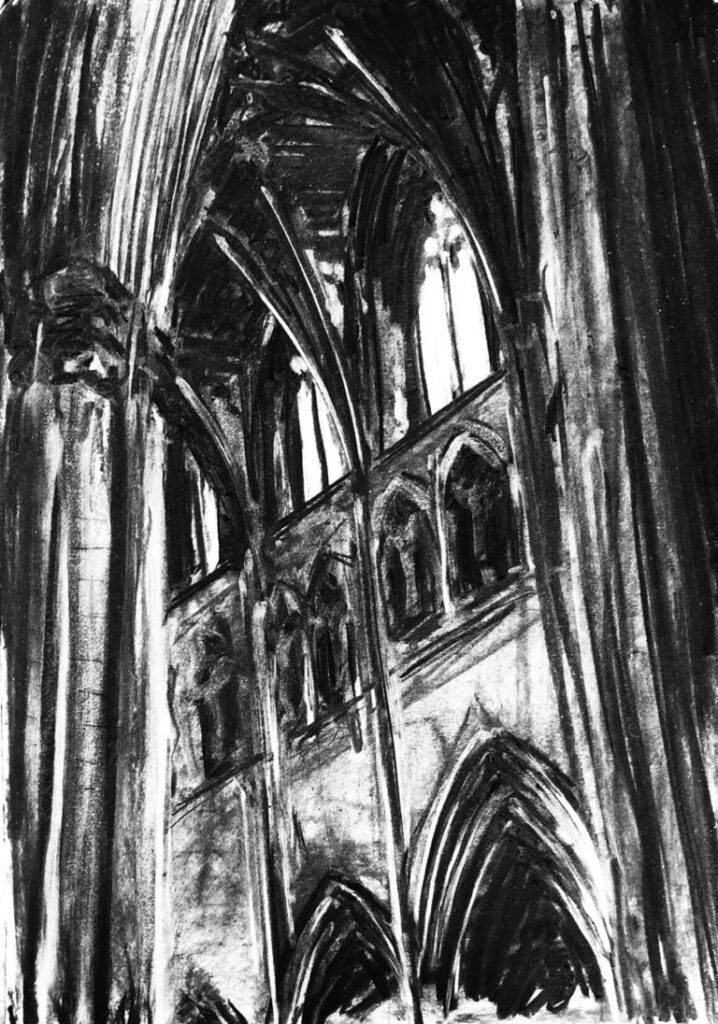

Image: Jeff (central, sideways) at his socially-distanced farewell gathering.

As I retire after 50 years as an AL in Religious Studies at the Open University, I have been asked to write something about what it was like in the early days. I can talk only of modules I have taught, of course; I never taught at Level 3.

I was appointed as tutor in November 1970, and the first courses started in February 1971. My first course (they were called courses, not modules, then) was A100. It had a small piece of RS—two weeks looking at Mark’s Gospel. I remember the word “pericope” figured prominently! So, this was a bit like the sort of thing I had studied in my first degree in Theology. I think there was an assignment on Mark’s gospel, but I am not certain about that. And certainly, RS did not figure in the exam at the end of the module, nor (at least in any major way) in the programme for the Summer School. (All students—nearly—then went for a week’s residential study at Bath, Keele, Stirling…) However, in a later Level 1 module (A102, I think,) religion played a big part in the study of Mid-Victorian Britain, and students generally loved that, particularly at Summer School.

In 1972, I started teaching A201 Renaissance and Reformation as well. There was a four-week block on the Reformation—Luther, Calvin, etc. My theology degree came in useful again! A201 was one of the best courses the Arts faculty ever produced, and the students loved it. In the exam, students did an inter-disciplinary question, and then (I think) two out of six options, one being the Reformation. The course team obviously thought ‘No-one is religious’; so they appointed teams of three or four markers for the other questions, but for the Reformation question they only appointed me. Out of 600 students taking the exam, 396 did the Reformation question. So much for making assumptions about students!

The first ‘proper’ RS course started in 1978—AD208 Man’s Religious Quest (no thought of gender bias then). It included an introduction to different approaches to studying religion, sociology of religion, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, African religion, Greek and Roman religion, Zoroastrianism, secular alternatives to religion, and “inter-religious encounter”. It was hard (I thought it was more like a Level 3 course than Level 2), but it included the opportunity to visit places of worship and that really brought it to life for many students. The students nearly all loved it and as I remember drop-out was very low. Many students talked about how it changed their perceptions, and in either the first or second year one student decamped to India to live in an ashram. I have no idea whether she ever came back!

After AD208 came three modules: A228 The Religious Quest (not so sexist)—a 30-point module, basically half of AD208, covering six world religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Judaism, Christianity and Islam)—followed by A213 and A217. These last two continued the same approach, studying the beliefs and practices of six religions, but with some extra themes. Incidentally, A217 had 7 TMAs, five of which were on five of the religions, but not Sikhism, which was a large part of the exam.

I taught two other modules, both 30 points. A231 (30 points) looked at religious diversity in Britain in the second half of the 20th century. Most students liked it, but it did not have large numbers and was not replaced at the end of its life. The other was AD252, Islam in the West. It was quite hard, but it appealed to quite a number of Muslim students and was generally liked. However, it ran only for four years and was also not replaced.

Numbers started high on the 60 point modules. I think on AD208 there were three groups in Region 08 (the North West), but by the end of A217 there was just one. And when A227 started I was the tutor for the North West and Yorkshire. It has become much more common for people to drop out than in the early days. I am not sure why this is, but I am pretty certain it is not the content of the modules that puts people off, though I will come back to that in a minute. I think the nature of our student body has changed a lot. For the first twenty years or so the OU was very much a ‘second chance’ university. Our students were largely people who had missed out on university in their teens, and were doing it partly out of interest and partly to prove to themselves that they were capable. For more of our students now the motivation is much more to do with career development, and that means that minority subjects find it more difficult to attract students. As to the higher drop-out, I am not really sure, I think the reasons must be complex and varied, but one factor is surely that there are so many more demands now on students’ time that OU study quite often has to be put on the back burner for a while.

I said I would come back to the content of the modules. Up until three years ago, all the Level 2 60 point modules were ‘world religions’ courses. The presentation differed but the content was largely similar. Many people (I was not one of them) came to see that as rather limited. So with A227 we have moved to a ‘lived religion’ approach. In my experience most students enjoy the module, but many say to me that it was not what they expected. They use different words for these expectations (‘theology’ or whatever) but a lot of them were expecting something like A217. In the past we had ‘Conditional Registration’ events. It was one of my favourite evenings each year. As tutor counsellor (don’t ask!) I would invite all my students (roughly 50, at all levels) to an evening at a study centre to look at course materials and discuss choices. So I could say to one student considering a module, ’Go and talk to Gladys – she did it last year’. There is far less chance to do that now, so I think it is more likely students will arrive expecting something other than they are going to get.

As regards A227, I have just discovered the OU’s ‘Why Religion Matters’ course on FutureLearn. It is short, so obviously has limitations, but it is a good way of starting to understand the approach on A227. I think all potential students should be encouraged to take it (it is free). Indeed, there are arguments for making it compulsory, though no doubt that would create lots of administrative problems.

Thanks for putting up with me while I have wandered down memory lane. I have loved almost every minute of the last fifty years.