The non-invitation of Boris Johnson at last week’s European Council on Ukraine came after a period of improved EU-UK relations, driven strongly by the Russian invasion. However, that close cooperation – highlighted by Liz Truss’ appearance at a Foreign Affairs Council earlier in the month.

So what gives?

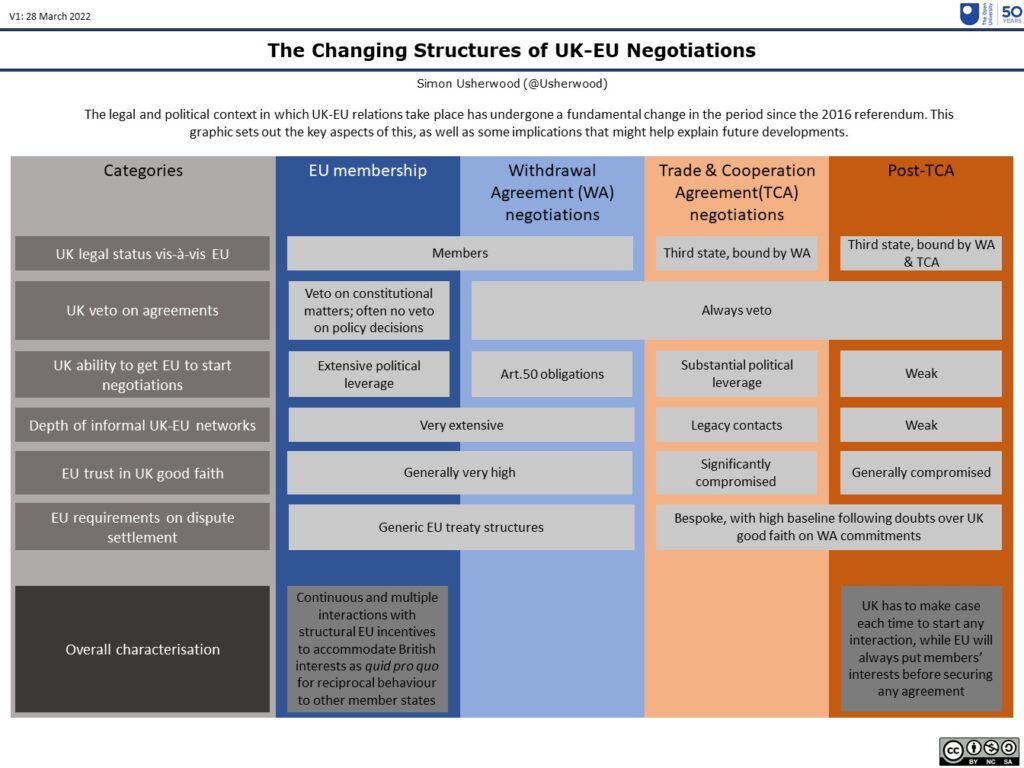

I’ve tried to set out so underlying reasons in the graphic below, but essentially the argument is that the UK is no longer an EU member state, so the terms of its relationship with the EU have fundamentally changed.

Within the EU, the UK had an institutionalised and a constitutionalised place at the table. That meant not simply a vote, but also participation in a set of practices that aim to keep all members together.

That means that should a state have a deep problem with a decision, other states (and the central institutions) will make considerable efforts to adapt that decision to allow the problem case to step back on. That doesn’t happen on more prosaic matters, when QMV kicks in on the understanding that it might not be the choice of everyone but it’s still within the bounds of acceptability.

This accommodation is reflected in the relative absence of a la carte integration: most members participate in most things, most of the time. When there’s a big issue – as with eurozone membership – then it’s made (effectively) optional, but with open doors for the rest to join later on (as they often do).

No one wants to be left behind, but not everyone can move at the same speed or in the same way, so mutually-supportive help is good for everyone. Look at Cameron’s renegotiation in 2016 for an example of how the system tries hard to work for a colleague in a spot.

Today, the UK doesn’t have that.

Instead, it’s a third country and so the EU will always put it clearly second to the needs of its remaining members.

Flex does occur, but within much tighter parameters set by those members’ needs: a concession to the UK will now only happen if it doesn’t damage the EU’s position relative to its internal politics.

Of course, the UK also is freed of the need to help out EU member states, and it holds an effective veto on all future cooperation outside the Withdrawal Agreement and Trade & Cooperation Agreement. But at the price of not having anyone else on its side of the table.

Those two agreements represented something of a transition and an aggravating factor.

Transitionally, the Commission did much to try to bridge the gap between the EU and the UK during both negotiations, especially under Art.50 when the British were still inside the system.

Aggravatingly, the intense difficulties of negotiating with the British and especially the accusations of not acting in good faith have strongly coloured current and future interactions. From the Internal Market Bill to the on-going tensions over the Northern Ireland Protocol, the UK has failed to give much confidence to EU counterparts that it will play by the rules it signed up to.

Trust is thus a chronic problem in the relationship and it’s this that helps explain Johnson’s absence last week.

The EU would like a constructive relationship with the UK, and it has been very happy that Ukraine has given reason for much working together, but the bonus of getting into the room with Biden and others requires more. The continuing appearance of Article 16 and the querying of certain EU members’ commitment to fighting Russia gave enough pause for thought for Charles Michel to not follow through on the tentative plans.

At one level, this is petty. At another, it’s not that important, especially given the NATO and G7 meetings around the European Council, where the UK did get its seat.

But it’s a mark of the long, hard road that the UK will have to grind along if it wants to regain the confidence of the EU. Actions and words will count, and for the time being, the presumption will remain that the UK cannot be trusted.

The EU would prefer to get along with the UK, but it doesn’t need to, so the UK is going to have to put itself out to get even the much-reducing status it can expect outside of the club. Whether the UK wants to do that is, of course, another question.