Judith George was appointed as a Classics tutor in 1973, teaching Classics courses steadily thereafter till the present, with A229: Exploring the Classical World. She became an Assistant Staff Tutor in Arts in 1975, Senior Counsellor in 1978, and Deputy Scottish Director in 1984. As well as teaching on OU Classics courses, acting as critical reader for a number, and writing Learning Guide 4 (Creating your own TMA) for A295: Homer, Poetry and Society, she took her Doctorate at Edinburgh University (part-time of course, as a typical OU single parent mum), with practical support from the OU’s Regional Academic Services, and from David Sewart in particular, a Director of that unit who was himself a classicist. The PhD was on the subject of Venantius Fortunatus, a sixth-century Italian poet who established himself in the developing courts of Merovingian Gaul, and proceeded to embed Latin literature and culture in that culturally aspirational society – Romanitas was the watchword of both secular and religious authorities (George, 1992).

Her time in the Scottish Directorate came at the exciting period of expansion of open and distant learning on all sides. She was heavily involved in many innovations for the country as a whole, including the piloting of new technologies for the support of OU students, and for education, business and industry in general, and the development of community education, Open Learning projects, a new Scottish Prison Scheme, and the creation of the University of the Highlands and Islands. She also acted as an international educational consultant, to disseminate OU experience and expertise in Scandinavia and in Europe. In all these activities, continuing as a Classics tutor and academic, and taking OU courses herself, was an essential element in keeping a vivid awareness of the experience of being a learner, which contributed to her developmental work and action research. She has published widely on Late Antiquity and educational topics. She was awarded a personal Chair in Educational Research and Development in 2001, an Honorary Fellowship in the University of the Highlands and Islands, and in 2004 an OBE in recognition of her services to higher and lifelong learning.

Transformation is the motif running through my experience as a classicist within the OU – personal, social, cultural, institutional. On the personal front, having read Greats at Oxford, it was naturally out of the question for me to teach in the Classics Department of the ancient university to which my husband was appointed – husbands and wives could not work together. The only work forthcoming was a teaching post in the Moral Philosophy Department – a post which, as Saki has it, was of ‘nomadic but punctual disposition’, consisting usually of my being phoned late on a Sunday evening in late September to be told that I was required to give classes on some aspect of Moral Philosophy from the following morning onwards. The pay was less than that of the departmental cleaners, and exam marking was onerous and unpaid. This did mean that my husband’s colleagues felt that they could now broach conversational topics with me on issues other than domestic trivia; but what was very frustrating was their total disinterest in what was actually happening in learning for their students. You could discuss their finances or their sex lives more readily than what was happening for their students. An apparently enthusiastic student, for example, kept on submitting work which I felt was seriously below her capacity. I eventually found out by chance that she had diabetes, was struggling to adjust her insulin levels, and had assumed that I was aware but just not willing to give help. The Head of Department, when I raised the matter, seemed quite shocked that I should be so intrusive and intimated that such interest in students, and especially in the circumstances of a student’s learning, was totally improper.

Transformation is the motif running through my experience as a classicist within the OU – personal, social, cultural, institutional. On the personal front, having read Greats at Oxford, it was naturally out of the question for me to teach in the Classics Department of the ancient university to which my husband was appointed – husbands and wives could not work together. The only work forthcoming was a teaching post in the Moral Philosophy Department – a post which, as Saki has it, was of ‘nomadic but punctual disposition’, consisting usually of my being phoned late on a Sunday evening in late September to be told that I was required to give classes on some aspect of Moral Philosophy from the following morning onwards. The pay was less than that of the departmental cleaners, and exam marking was onerous and unpaid. This did mean that my husband’s colleagues felt that they could now broach conversational topics with me on issues other than domestic trivia; but what was very frustrating was their total disinterest in what was actually happening in learning for their students. You could discuss their finances or their sex lives more readily than what was happening for their students. An apparently enthusiastic student, for example, kept on submitting work which I felt was seriously below her capacity. I eventually found out by chance that she had diabetes, was struggling to adjust her insulin levels, and had assumed that I was aware but just not willing to give help. The Head of Department, when I raised the matter, seemed quite shocked that I should be so intrusive and intimated that such interest in students, and especially in the circumstances of a student’s learning, was totally improper.

Appointment to the OU was a revelation. I had colleagues who were passionately interested in students’ learning; the focus of the Foundation courses was on creating a level baseline for students coming from unimaginably diverse backgrounds, so that they then had the capacity and the skills to move on to higher level courses. We spent our time devising support systems, ways of giving advice and guidance, strategies for compensating for life circumstances – it was wonderful. I remember vividly the first month of the first Classics course I taught, being contacted by a student on the Scottish Borders, who apologised profusely for his work being late, but explained that the lambing had started early this year. Such passion for Classics, interwoven with the classical shepherd’s calendar, had a vivid reality and weight rarely found in the conveyor-belt teenagers of privilege. So teaching Classics in the OU was a transformation to an institute where students not only mattered, they were the be-all-and-end-all of our professional work; and where studying Classics was a matter of passionate commitment.

I had always wanted to do a PhD, but had been unable to up to that point. Occasional translation work for the Professor of the History of Fine Art at Manchester had got me hooked on the question of what people hung on to and why as the so-called Dark Ages rolled over them. So I enrolled to do my doctoral work at Edinburgh, with the warm support of Regional Academic Services, on Venantius Fortunatus and his part in the transmission of Romanitas in sixth-century Gaul. Teaching for the OU had moved me substantially away from the narrowly compartmentalised traditions of Classics to the interdisciplinary approach of Ferguson (see Lorna Hardwick’s blog), and teaching A100 had also highlighted the vivid impact of poetry on people new to its world. All this fed into my approach to Fortunatus, in a field, the then-called Dark Ages, at a time when there was little interest and even less current scholarship, creating the space to expand and experiment with approaches. So Classics in the OU gave me the chance to move to doctoral level, and also the scholarly framework within which to innovate and be creative.

And being a Classicist member of the Scottish directorate enabled a distinctive OU contribution to the continued existence and vitality of scholarship in Late Classical Antiquity in Scotland. In the mid-80s, these departments were on the brink of extinction. A couple of friends and I created EMERGE (the Early Medieval Europe Research Group), which brought together Insular and European scholars from across Scotland at least twice a term, for a convivial and supportive supper in the OU’s splendid Edinburgh centre, followed by an excellent paper, usually from an internationally recognised scholar. This raised morale, fostered interdisciplinary thinking, strengthened people to resist erosion and cuts, and encouraged younger students.

And being a Classicist member of the Scottish directorate enabled a distinctive OU contribution to the continued existence and vitality of scholarship in Late Classical Antiquity in Scotland. In the mid-80s, these departments were on the brink of extinction. A couple of friends and I created EMERGE (the Early Medieval Europe Research Group), which brought together Insular and European scholars from across Scotland at least twice a term, for a convivial and supportive supper in the OU’s splendid Edinburgh centre, followed by an excellent paper, usually from an internationally recognised scholar. This raised morale, fostered interdisciplinary thinking, strengthened people to resist erosion and cuts, and encouraged younger students.

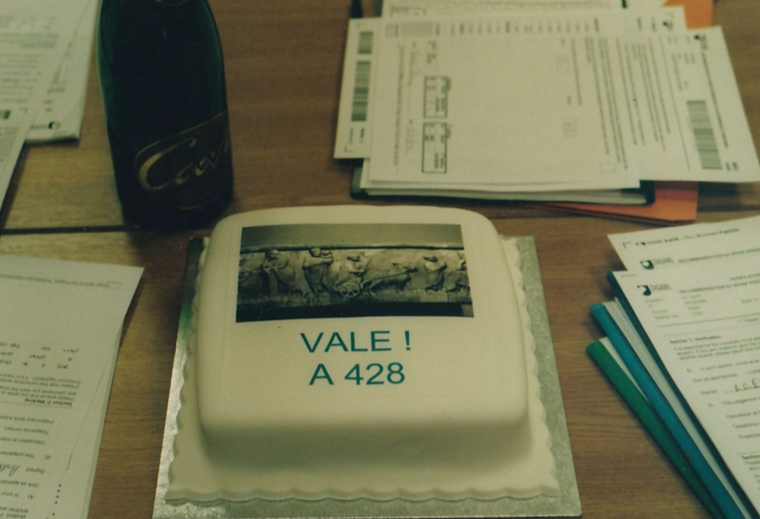

Being a ‘country member’ of the Classics Department and involved as a critical reader was also a great privilege. Apart from the fascination of crafting learning material across various media, it kept me in touch with a range of scholarly disciplines and gave me colleagues who have become lifelong friends. And it also gave me the chance to experiment with reflective learning. I designed Learning Guide Four of A295: Homer, Poetry and Society, to talk students through the process of choosing a topic which had one foot in Homer and the other in any topic of interest to them, formulating a question and answering it. This was a loosely formulated remit, deliberately so to give them the chance to be experimental and creative – so the Learning Guide talked them through the process of reflecting on their strengths and weaknesses as learners, on choosing appropriate formats of question, and then constructing a solid and sound argument. The results were fascinating. We inevitably had a solid cluster on women’s role in the poems and the society, but also ones which were totally unpredictable. A surgeon produced a vividly illustrated assessment of the wounds described in the Iliad, demonstrating that the accounts reflected a sound practical knowledge of the impact on human anatomy of a spear striking from this angle or an arrow penetrating from that. Quite gruesome, but quite clearly these descriptions were not purple passages. We had thoughts on birds in Homer from someone in Shetland, and many other idiosyncratic but valid topics. So working through Block 5 of A229 (Exploring the classical world: End-of-module assessment preparation) with my current students these past weeks has being revisiting that territory with pride that this has become embedded in our Classical teaching!

Classics has always also reflected the wider culture of society, and there has been transformation here too. In the first year of teaching students on the Isle of Lewis, I had fundamentalist Wee Free Presbyterian students who were enthusiastic, but totally paralysed by being expected to look at and even discuss representations of nude figures, especially female ones. And there was the audio conference call, drawing eight or so students across Scotland together for a discussion of Euripides. All was going smoothly, until I heard a strong intake of breath on one of the lines, and a stressed voice launched into the charge that we were discussing FAKE TEXTS – everyone knew that the Greeks were fine, upstanding folk, but this play was filthy and debased, so it could not be a true Greek text. That tutorial took quite a bit of handling! But times have changed. Naomi Mitchison, the author, receiving an Honorary OU Doctorate at a ceremony in Glasgow, spoke of the OU having lit candles in every little community the length and breadth of the Highlands and Islands, which illuminated and transformed them. She was right – the OU, and Classics playing above its weight, has broken barriers and brought people together in understanding and acceptance. Or has it? Inga Mantle, another OU classicist, is producing Aristophanes’ Ecclesiazusae in June this year. She has been banned from her usual venue by a church minister outraged by a frisky new translation, no longer clad in the decent obscurity of a learned language or more bland English!

Classics has always also reflected the wider culture of society, and there has been transformation here too. In the first year of teaching students on the Isle of Lewis, I had fundamentalist Wee Free Presbyterian students who were enthusiastic, but totally paralysed by being expected to look at and even discuss representations of nude figures, especially female ones. And there was the audio conference call, drawing eight or so students across Scotland together for a discussion of Euripides. All was going smoothly, until I heard a strong intake of breath on one of the lines, and a stressed voice launched into the charge that we were discussing FAKE TEXTS – everyone knew that the Greeks were fine, upstanding folk, but this play was filthy and debased, so it could not be a true Greek text. That tutorial took quite a bit of handling! But times have changed. Naomi Mitchison, the author, receiving an Honorary OU Doctorate at a ceremony in Glasgow, spoke of the OU having lit candles in every little community the length and breadth of the Highlands and Islands, which illuminated and transformed them. She was right – the OU, and Classics playing above its weight, has broken barriers and brought people together in understanding and acceptance. Or has it? Inga Mantle, another OU classicist, is producing Aristophanes’ Ecclesiazusae in June this year. She has been banned from her usual venue by a church minister outraged by a frisky new translation, no longer clad in the decent obscurity of a learned language or more bland English!

So, a very Happy 50th anniversary to this remarkable institution, in which we have all been so lucky and privileged to be caught up.

Bibliography

George, J.W. (1992), Venantius Fortunatus: a poet in Merovingian Gaul (Clarendon Press, Oxford).