Over the last few months, several OU Classical Studies students and graduates have been involved in setting up a new organisation called Asterion, which aims to represent neurodiversity in Classics.

For the OU Classical Studies Blog, Asterion Director and OU tutor Cora Beth Fraser caught up with two neurodivergent members of the Asterion Editorial Board, Hilary Forbes and Tony Potter, to talk about neurodiversity, OU study and Asterion.

Cora Beth: In setting up Asterion, I’ve been hearing a lot of late-diagnosis stories from people who’ve only found out in adulthood that they are neurodivergent. For many people the diagnosis explains traits and problems that go back a long way. It certainly has done for me. After I was diagnosed as autistic in my 30s, I could look back at my childhood and see all the quirks and difficulties that would have added up to an obviously autistic profile, if I hadn’t been trying so hard to hide them, and if autism hadn’t been so little understood in those days! How about you: when did you first realise that you experienced the world a little differently?

Tony: I think I’ve always known I was different and that I experienced the world more sensitively than others from my early childhood. Even in primary school I was called a ‘quirky’ child. I remember being told off for having a sort of nervous tick when I got stressed out. I also remember it being referred to as a habit that I’d grow out of. Now however, I see it for what it was, it was a physical manifestation of a condition that at the time I knew nothing about and it was brought on by factors outside of my control. Plus, we’re talking about the late eighties and early nineties here and neurodiversity wasn’t really something that got loads of attention back then. This is the bizarre bit though; in my later teenage years I seemed to do exactly what had been predicted and grew out of it – well, at least that’s what I thought. I sailed through my early twenties with ease. I think this was because I lived in another country and was essentially a different person. I’d escaped my upbringing, so to speak. I worked as a holiday rep for five years and didn’t seem to experience one bit of OCD or anxiety. On the contrary, I would stand up in front of hundreds of people to conduct welcome meetings, I was outgoing, confident and very adventurous and I partied really hard (perhaps too hard if truth be told), but none of this bothered me one bit and any suggestion that I suffered from a mental condition would have had me rolling on the floor in fits of laughter.

It wasn’t until my late twenties to early thirties that I started to experience the world differently again. I could feel myself becoming more and more conscious of my surroundings and how I felt I was being perceived by other people. I think what triggered my OCD and anxiety after all those years was my working environment which at best could be described as stressful and at worst, toxic. There was a very unpleasant culture where I worked at the time, and day in day out people feared for their jobs because the company turned over staff like it was a competition. I personally think that spending three years in that environment sort of broke me. It wasn’t until I bit the bullet and left the business that I felt more secure, but unfortunately the damage had been done and the anxiety and OCD were back to stay.

Hilary: I think I’ve always known this for as long as I can remember… but I couldn’t express it as a child. I used to think that all the other children at school were in on some secret which I didn’t know, and that’s why they all seemed to be able to communicate with one another, when I didn’t know how.

I have always wanted to know how things worked – from the time when I undid all the nuts on my pram (it nearly collapsed while I was being pushed in it because I did it so quietly and without being seen… but I was fine – it was saved just in time!), to taking radios to pieces. Everything that could come apart, I took apart to see how it worked, so science was a big draw to me. But so was English Literature because I enjoyed learning about how novels and plays were constructed and the context of them, so I was a big Shakespeare fan… so for me delving deep into the possible influences of the ancient world on current science was and is part of the same path. I tend to see history, science, theology etc as one thing rather than chop them up into different disciplines.

Cora Beth: I know you’ve both been studying for a long time. My own path through education has been a winding one: I’ve completed a bunch of degrees in different subjects – and gotten part-way through several more – because when I take an interest in something, I find myself needing to know everything about it! What have your education journeys been like, and how did you end up in Classical Studies?

Hilary: I came to Classical Studies as a natural (to me) progression from Astrophysics and Theology… I know it seems strange, but it makes sense to me! I have had a love of all things astronomy and the night sky since I was four years old and that developed into a BSc in it, and I followed this by a BD (specialising in Old Testament Lit and Lang). However I did these degrees many years ago back in the early 80s and so I have come to Classical Studies quite late in life after a career as a secondary school and then FE maths teacher and after thirteen years of also teaching Astronomy GCSE in FE. Then around fourteen years ago, I found Aristarchus of Samos, who lived around the end of the 3rd and throughout most of the 4th century BC. He was the first person who has been referred to as proposing that the Sun was at the centre of the then known Universe, and that he did this 1800 years before Copernicus did fascinated me.

After reading as much as I could for many years and considering various MA s, I came across the Classical Studies MA at the OU. I love context, and so it satisfied two aspects of study for me, studying the context of ancient cosmologies – and by context I mean, what was everyday life like for the ancient Greeks and Romans? It also gave me a way in to study more of the context of the Roman world in the time of Christ, and the events referred to in the New Testament. Of course, having come now to the end of this MA, I feel I have only just begun to dip my toe in the water…

Tony: I enrolled with the Open University in 2009 and at the time it wasn’t possible to do a degree in Classical Studies alone, so I registered for the BA (Hons) in History. Luckily for me there was a good range of modules available so I was able to tailor my degree pathway to my interests and ended up making up almost 50% of my degree with Classical Studies related modules. Starting in 2009 I studied one 60 credit module per year. I started with AA100: The Arts Past & Present, followed by A219: Exploring the Classical World. I then completed A200: Exploring History: Medieval to Modern followed by A330: Myth in the Greek & Roman World. In my final two years I studied A330: Empire, and finished my degree with A223: Early Modern Europe. So, as you can see, my degree was very varied – but I enjoyed every part of it! I caught the OU bug very shortly after enrolling on my first module so continuing with an MA in Classical Studies after my undergrad degree was finished was a no-brainer for me. Although it has taken me longer than I would’ve liked to complete my MA, owing mainly to a rather inconvenient flare-up in my OCD and anxiety, I’m very pleased to be at the stage I am now.

When I started with the OU in 2009 I wanted to get into secondary teaching. Although teaching in some form or other is still my long-term goal I now know that I’d be better suited to the type of teaching that takes place in further and/or higher education environments. Now that I’ve completed my MA, though, I’m planning a PhD, so hopefully I’ll be a student of the OU for bit a longer! I can’t honestly say with any certainty where I’ll end up after my OU journey, but I know whatever happens I’d love to be involved with Classics and Ancient History and I certainly want to continue researching. Perhaps I’ll apply to become an OU tutor!

Cora Beth: I know that in my own career as a student, and later as a teacher, I’ve had to put a lot of strategies in place to help me, because my autistic brain struggles with certain things. I’ve learned, for instance, that emails tend to overwhelm me – it can take me an hour to compose an answer to a simple query, because I find it so difficult to get my meaning across without misunderstanding. So for me, emails have to be tackled at the right time of day, and in short bursts. Do you find that you’ve had to make adjustments or invent ways of approaching your work differently, because of your neurodivergence?

Hilary: I much prefer learning in my own time and space at my own pace. I enjoy not having to engage with many other students in groups and I have enjoyed especially not having to have my webcam on during tutorials – thanks, Cora Beth, for not asking us to do this…!

This all makes me sound horribly unsociable! I am quite sociable really – but in particular ways when I have the energy to be so, and not in groups or crowds. I did attend one OU conference and it was really lovely to meet people but it also wiped me out for a week or two afterwards so there is a cost to being social around more than three people. The flexibility of the OU also allows study to fit in around work, which is the other major reason it works so well for me.

Tony: I suppose I’ve subconsciously adapted my study methods to appease my OCD and anxiety. For example, one problem I have resulting from my OCD is that I seek perfection in anything I do, or in this case, anything I write which is both physically and mentally exhausting. I’ve tried hard to accept that there’s a point when a piece of work is as good as it needs to be but this just doesn’t work for me so I still strive for perfection. Because my writing style (not sure if ‘style’ is the best word to describe this though!), is a relentless cycle of write, review, delete and repeat, it takes me much longer to get a polished piece of work across the finish line ready for submission. For this reason, over the years I’ve had to be very pro-active in my approach to TMAs. I would start early and work on the little but often approach. I tended to write my TMAs as I worked through the module readings, ending up with a conglomeration of ideas which I could then mould into a coherent piece of work. This approach was exhausting and time consuming, but it was the only workable method I could use.

Luckily for me, I developed a better approach throughout my MA. I still massively over complicated things and made my life very hard, but it worked better for me. I’m still striving for the elusive ‘perfect’ approach (I’m not even sure that exists), and hopefully if I do get on a PhD programme, I’ll have the time to work on that. Despite my convoluted processes though, I always seemed to produce very good work which was at least a reward for the hours I spent polishing my essays.

Cora Beth: You’re both serving on the Editorial Board of Asterion, alongside neurodivergent classicists from schools and universities around the UK and overseas. Why do you think an organisation representing neurodiversity is needed in Classics?

Tony: Despite a great deal of hard work and tireless effort by a lot of very committed people in our field, the word ‘Classics’ still carries lots of negative connotations, and the perception of it being an ‘exclusive club’ of sorts still persists. Although our field is no longer dominated by elite white males with old-fashioned opinions, it remains difficult to shake off these historic biases. In a world where more and more people are coming to terms with their own mental health and neurodivergencies it’s never been more important to embrace this diversity in our field, particularly if it’s to survive well into the future and become an ‘all-inclusive’ discipline. Classics is a multifaceted and enormously varied area of study and researchers in our field are now regularly exploring the links between neurodiversity and the Classical World, which makes our presence as neurodivergent individuals more and more essential to the future of the discipline.

Hilary: There is a great need generally to raise awareness of neurodivergent people and how we view the world. In the world of Classical Studies – at any level of enjoyment – it is great to have a place which welcomes those who have had experiences of not fitting in anywhere. To be accepted and valued is the one thing we all need.

If you’d like to find out more about the work Asterion is doing, visit our website at https://asterion.uk/ and read our blog. We welcome enquiries and new members – so if you’d like to get in touch, do send us an email at [email protected], or pitch us an article at [email protected]!

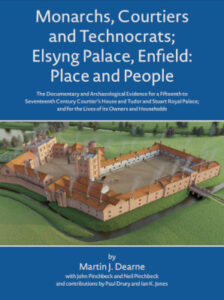

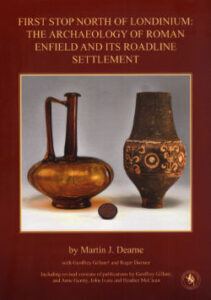

Dr Martin Dearne has been an Associate Lecturer with The Open University for twenty years, and has taught on many of our Classical Studies modules (AA309, A209, A251, A330, A219, A229, A105, A151, A112). He is the author of six books, the most recent of which is an archaeological study of Elsyng Palace in the London Borough of Enfield. In this blog post, Martin tells us more about

Dr Martin Dearne has been an Associate Lecturer with The Open University for twenty years, and has taught on many of our Classical Studies modules (AA309, A209, A251, A330, A219, A229, A105, A151, A112). He is the author of six books, the most recent of which is an archaeological study of Elsyng Palace in the London Borough of Enfield. In this blog post, Martin tells us more about  Hello Martin, and congratulations on your new book! Please could you start by introducing our readers to Enfield and its history?

Hello Martin, and congratulations on your new book! Please could you start by introducing our readers to Enfield and its history?

Two years ago we published a ‘

Two years ago we published a ‘