Theo Wildcroft, PhD Candidate

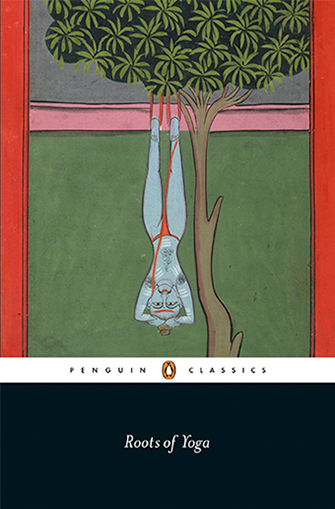

Roots of Yoga, authored by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, is the first major text from one of the most significant research projects into the history of hatha yoga, the familiar form based on postures. As such, the book has been eagerly awaited by scholars and practitioners alike. Whilst contemporary yoga has become globally popular through the last century or more, the source material for that globalisation is surprisingly narrow.

Roots of Yoga, authored by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, is the first major text from one of the most significant research projects into the history of hatha yoga, the familiar form based on postures. As such, the book has been eagerly awaited by scholars and practitioners alike. Whilst contemporary yoga has become globally popular through the last century or more, the source material for that globalisation is surprisingly narrow.

Roots of Yoga aims to bring to light more of the vast diversity of pre-modern hatha yoga practice. It collates curated extracts from original pre-modern texts, together with an analysis of common themes and differences. It also acknowledges non-Indian and non-Hindu influences that are mostly omitted from non-academic accounts of hatha yoga. This bold choice will have political as well as scholarly implications.

The reception of historical yoga scholarship beyond the academy can be fraught. The narrow source material of most contemporary yoga was reformed in the pre-independence period, invigorated with transnational influences, combined with medical terminology and neo-Vedantic philosophy, and promoted as an enduring, ancient, authentically Indian practice for holistic health. That practice eventually proliferated into global significance, still trading on associations with authentic Indian roots, but increasingly subject to commercial appropriation. One overt aim in recent years for both American activists for social justice and the right-wing Hindu nationalist Indian government is to ‘return’ yoga to control by its perceived culture of origin. This has become entangled with politics of caste and sect, and denies the long history of multi-faith syncretism shown by Roots of Yoga, as well as a century of transnational innovation within the evolution of yoga. As such, the reception of new historical commentaries on yoga has become highly politicised.

Few would wish to repeat the experience of Wendy Doniger, whose The Hindus was removed from sale in India following governmental pressure. But as a researcher of contemporary, rather than historical practice, I find that it is in social media spaces that the impact of new scholarship is first felt beyond the academy. Mark Singleton’s previous book, Yoga Body, had a powerful impact on the transnational yoga scene. Followers of the Mysore lineages have understandably been the most resistant, whilst secular reformers and post-lineage innovators alike find in the book a strong justification for their own evolution of the practice.

The most common dismissal of Mark’s work, and that of other academics, is that mere scholars as non-practitioners can only have the most superficial of understandings of the practice. Although Mark is a yoga practitioner, his co-author James Mallinson is much more demonstrably so, having appeared in a BBC documentary on the Kumbh Mela being ordained as a mahant. With copies of Roots of Yoga in just a few practitioner hands so far, it has already become common to respond to critics dismissing the book with a link to the BBC documentary.

Already, Roots of Yoga has both fervent supporters and critics who refuse to read it, organising along lines of sect and politics. So far, the most interesting review is that by the yoga writer and thinker Matthew Remski, for Yoga Journal. It perfectly encapsulates many of the contradictory forces currently acting upon transnational yoga culture.

The review’s title is “10 Things We Didn’t Know About Yoga Until This New Must-Read Dropped”, a click-bait title that makes its writer uncomfortable. Within the very short word limit, Matthew does his best to drop a number of key facts, focusing on core concerns of contemporary practice: the historical place of women in yoga, cultural diversity and appropriation, physical and emotional safety, body image and the clash between scientific and pre-modern epistemologies. Yoga Journal chose to accompany the article with links to less serious links such as ‘A Beginner’s Guide to the Chakras’, as well as exactly the kind of images of normative bodies that yoga cultural commentators like Matthew criticise in their writing. It leads to the delightful incongruity of number 8: “’Yogic suicide’ is a thing” illustrated by a woman sunbathing in a bikini. It’s an image that could be screenshot and used in any lecture on contemporary transnational yoga culture.

Roots of Yoga, authored by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, is the first major text from

Roots of Yoga, authored by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, is the first major text from

For each side, allowing the other side to instil their values into the child is tantamount to doing violence to them. Therefore, it can in some cases become permissible, even necessary, to commit violence to prevent this. This might well illustrate the claim by Stuart Wright later in the conference that violence is by no means an inevitable outcome of millenarianism, nor the result of some essential quality or attribute. Rather it is one possible result of the relationship between the groups and other groups, particularly legal or military, which represent the official state. Until the 1980s, the anti-cult movement relied predominantly on charges of brainwashing to encourage state intervention in NRMs. A brainwashed individual was essentially one stripped of agency and free will. The concept derived from the USA’s Asian wars of the 1950s to ‘70s, to explain why some GIs would defect to the other side. Few psychologists accept the existence of brainwashing today, however, so perhaps this is why the charges against NRMs increasing concern children.

For each side, allowing the other side to instil their values into the child is tantamount to doing violence to them. Therefore, it can in some cases become permissible, even necessary, to commit violence to prevent this. This might well illustrate the claim by Stuart Wright later in the conference that violence is by no means an inevitable outcome of millenarianism, nor the result of some essential quality or attribute. Rather it is one possible result of the relationship between the groups and other groups, particularly legal or military, which represent the official state. Until the 1980s, the anti-cult movement relied predominantly on charges of brainwashing to encourage state intervention in NRMs. A brainwashed individual was essentially one stripped of agency and free will. The concept derived from the USA’s Asian wars of the 1950s to ‘70s, to explain why some GIs would defect to the other side. Few psychologists accept the existence of brainwashing today, however, so perhaps this is why the charges against NRMs increasing concern children.