This piece was originally published on the UK in a Changing Europe site.

It’s something of a truism to say that Brexit is a process, not an event, but nowhere is this more evident than in the UK’s continuing difficulties in managing the pieces of legislation it adopted during its time as a member state of the European Union (EU).

As we close in on a decade since the 2016 referendum, it is apparent that there is still no final and definitive list of that legislation, nor clarity about what should be done with it all. With multiple negotiations in train on renewed cooperation between the UK and the EU, that will raise increasing problems for both sides.

Following withdrawal, the then-Conservative government largely turned its back on things European; partly because of the Covid-19 pandemic and partly because of the intense discomfort the issue had wrecked within the party over the previous decade. But one area that continued to pop its head up was Retained EU Law (REUL) – assorted Statutory Instruments, primary and secondary EU legislation, case law and more which the UK adopted as a member state, and copied over as ‘assimilated’ UK law during the Brexit process.

Business Secretary, Jacob Rees-Mogg, introduced legislation in September 2022 which would see all REUL expire by default at the end of 2023 under a ‘sunset clause’, except in cases where ministers actively chose to retain or reform specific pieces. That legislation, which was to become the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act, was intended to mark a definitive break with REUL and a restoration of British sovereignty.

However, it very quickly became apparent that there was no clear record on what that might cover, which made it impossible to know whether it served any useful function or whether revocation might cause unanticipated consequences for either domestic or international obligations. With much push-back from legal scholars, businesses and other groups, as well as backbench rebellions, the final Act took a much more limited approach, abandoning the sunset clause and instead revoking only 600 items of REUL, while instigating a process for identification and review of everything else.

This process centres on a database – the REUL dashboard – which details every known item of REUL and case of reform. It has just had its regular six-monthly update, to list some 6,925 items, alongside regular reports to Parliament on progress.

The latest update is the eight substantive revision of the database from its original 2,417 items in January 2023 and marks approximately two years since the last step-change in the overall picture. Back in early 2024, over 1,700 new items were added, following the completion of a new scoping exercise across Whitehall.

Since that point, a further 168 items have joined the list, including 14 in the most recent period. This discovery includes EU decisions similar to those that have been on the Dashboard for years, and domestic legislation nearly 30 years old, highlighting the difficulty of ensuring a comprehensive coverage.

But such top line figures, which are the lead indicator on the Dashboard, mask a second kind of problem; namely that the data isn’t as robust as you might expect, or as is needed for this entire exercise to have meaning.

The database still contains several items that are there as queries as to their possible inclusion. Such cases have occurred before – for instance the removal of initial entries about the effect of several articles of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU.

There are also instances where multiple references to specific provisions of an item have been rolled into a single entry, as with the Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992, which started as four separate elements.

However, more common has been a one-off entry that appears to be within scope of the REUL Act, but then seems to disappear. To pick one example, the January 2023 list mentions Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2018/631, which appears to have been revoked in 2020, but then disappears from the database entirely. While this might be understandable as something pre-dating the exercise, it is noticeable that the previous item in the database, Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2018/63, was similarly repealed in 2023, but still remains present.

Different again is the Sexual Offences Act 2003. The January 2023 entry clearly indicates its role in implementing an EU Council Decision that was subsequently listed in the database, but which makes no reference back to the Act. While these might be treated as a package, the lack of complete cross-linkage makes it very hard to know what item has what status.

In total, while there are 6,925 entries in the current Dashboard, it is possible to identify approximately 7,500 unique entries across the period since the first release. Some 600 items that appeared at some point in the past (often more than once) are absent from the Dashboard today.

Such inconsistencies are a function of the complexity of the UK’s membership of the EU. Some 40 years of incorporating a large volume of legislation – often through secondary instruments – with no immediate need to keep comprehensive and exhaustive records has left an almost impossible task for those in the Department of Business and Trade who run the Dashboard.

However, given that the programme of reviewing Assimilated EU Law appears continues under the Labour government, with 22 amendments and 19 repeals in the last six months, the need for clear, consistent and accessible data remains as high as ever.

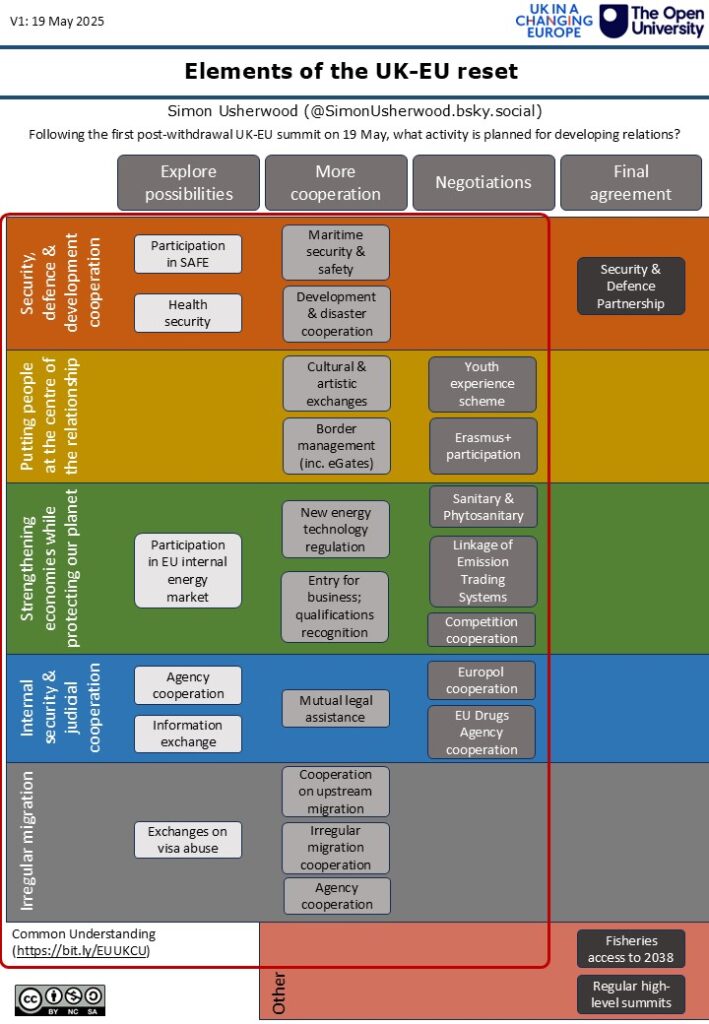

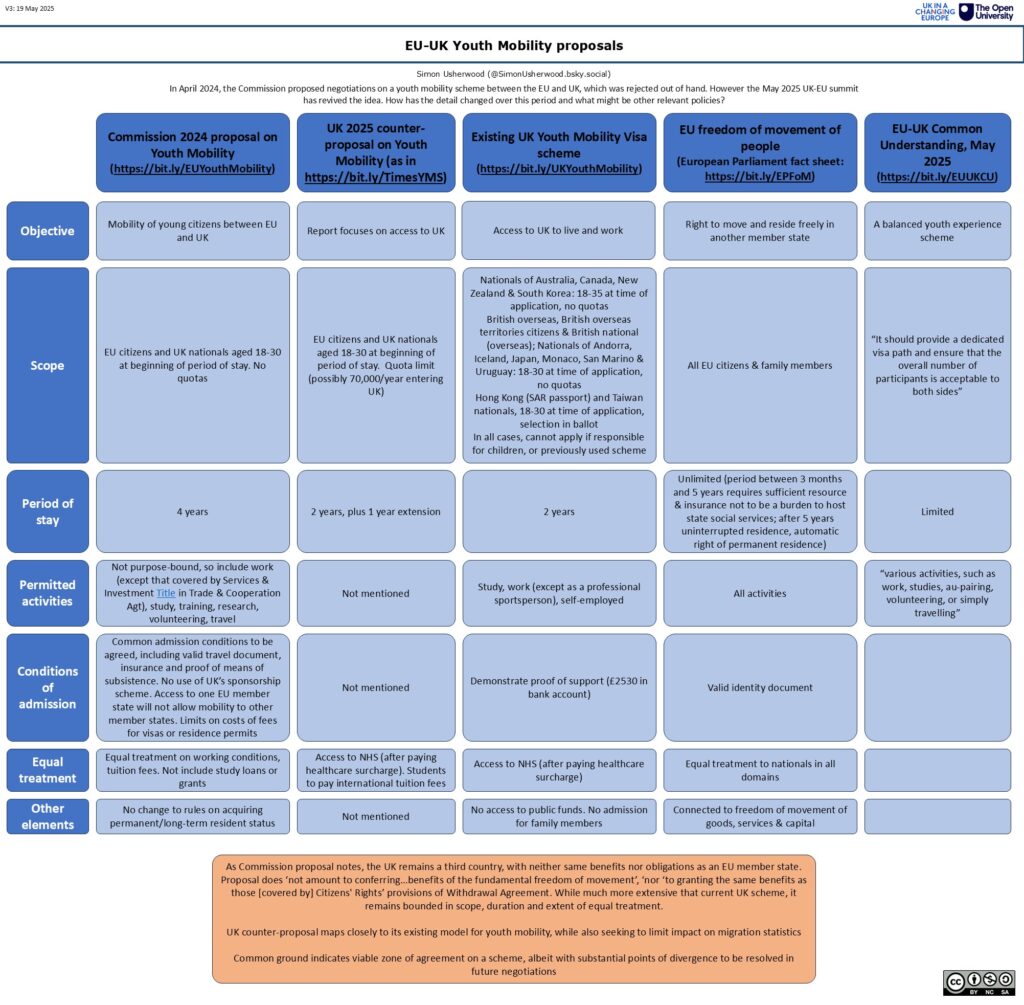

At the same time, the demand on resources within the civil service to conduct such reviews also represents an opportunity cost, especially at a time when the government is embarking on multiple negotiations to pull the UK closer towards the EU in legislation-rich topics such as sanitary and phytosanitary standards and emissions trading.

Absent a clear strategic objective, there is a risk that officials spend time reviewing, amending or repealing REUL which they will soon have to be reinstate or amend once again: from decisions about SPS processes to regulations verification of emissions data.