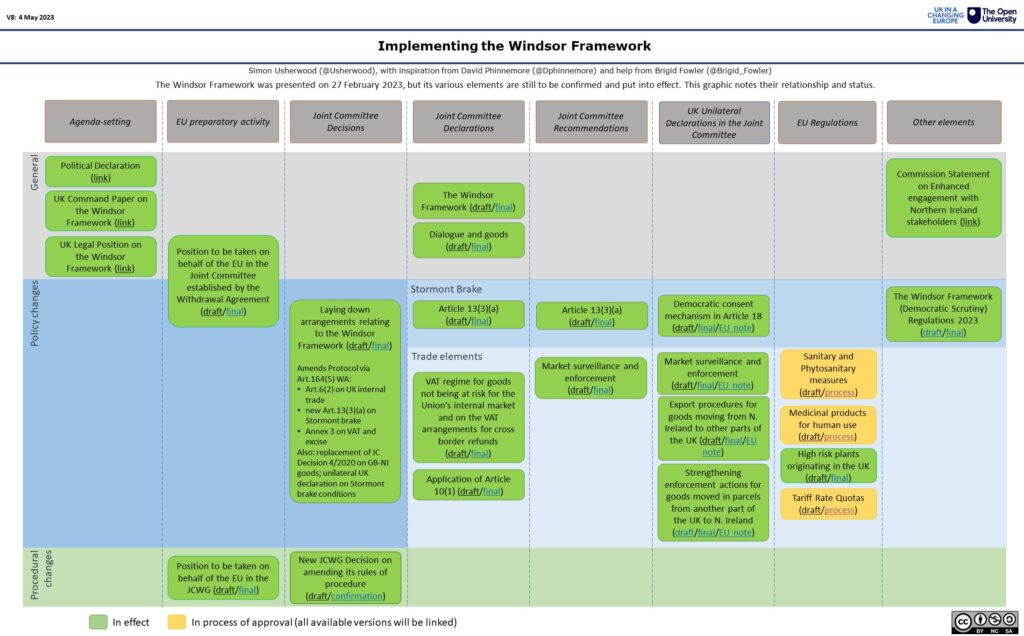

We’re now at a point where it’s possible to say that almost all of the Windsor Framework’s numerous elements are now either fully adopted or (for a handful of pieces of EU legislation) in the process of agreement.

That might make for a nicely-coloured graphic, but what does it actually mean on the ground?

As various people noted when I tweeted this out, having the legal adoption of a text doesn’t immediately mean it comes into effect, something that was being noted by the witnesses at the Lords Protocol Sub-Committee evidence session yesterday.

Partly that’s because of the provisions of the decisions themselves.

Article 23 of Joint Committee Decision 1/2023 (the key document in all this) sets out a number of different dates for entry into force of provisions. The default date is 30 September 2023, with only a handful of elements immediately in force.

It’s also worth noting that that default date only produces an entry into force if the EU is satisfied about access to UK information, EORI paperwork is correctly issued, the UK has guidelines in place on parcels and NI-GB goods export. No satisfaction, no operationalisation of the provisions.

There’s another reason too, namely the lack of UK documentation to clarify process (h/t to @irishagreement for this).

The government’s Border Target Operating Model will be the new standard system for goods movements across the UK’s borders, but this will only fully come into effect at end October 2024. Moreover, it specifically notes the Windsor Framework’s agreement and says new arrangements will be forthcoming ‘later this year’.

In both cases, the focus returns to UK capacity, rather than EU-UK agreement per se.

This was largely obscured during the time of the Johnson administration: the policy of contesting the Withdrawal Agreement’s provision (and status) meant that building effective systems necessarily took a bit of a back seat. This January’s agreement on a basic system of information-sharing can only be partly explained by the technical issues involved.

But IT is only one part of the infrastructure and process involved, as the Border Target Operating Model makes clear. From the EU’s perspective, making sure that this is all in place is understandably important, given the need to protect against any future backsliding by a UK government that doesn’t have a perfect record (and that might be out of office relatively soon).

This would have been the case even without Windsor: last year’s infringement procedures (now suspended) were precisely about such issues.

Even at arm’s length, interaction with the EU comes with obligations, something that will only become more evident as new areas of cooperation are developed.