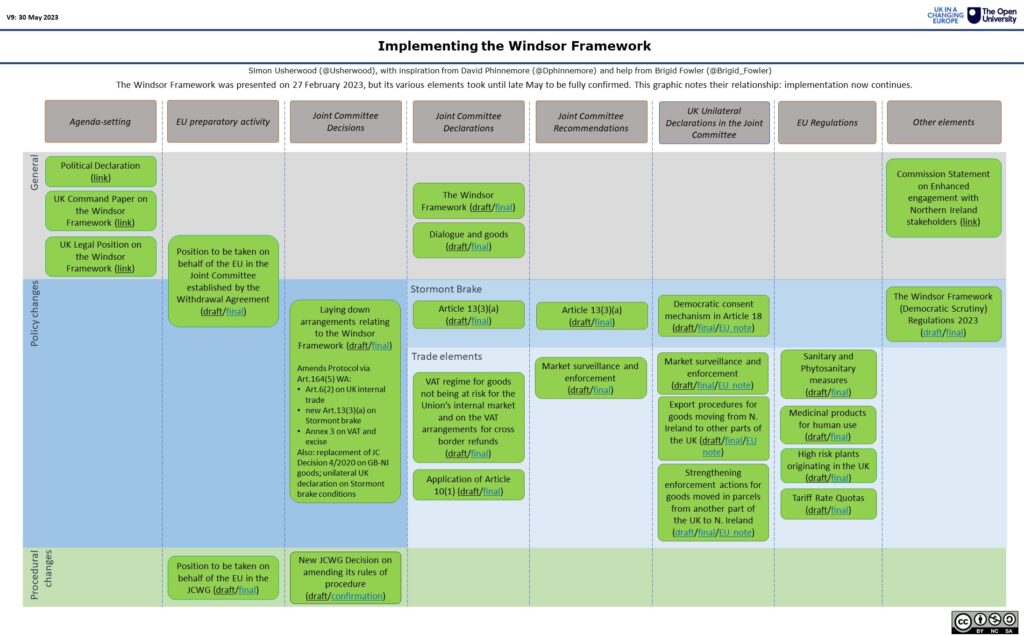

This week’s announcement from the Council on the adoption of three Regulations marks the end of a rapid process of enacting the Windsor Framework.

As discussed earlier this month, while the February photoshoot in leafy Surrey [my local news sources were very adamant about it not being even Berkshire, let alone Windsor] was good for headlines, it wasn’t much more than a set of commitments to enact a bundle of items.

While the Joint Committee‘s meeting within a month permitted much of that content to be moved into the rule books, even with an accelerated procedure the EU has needed a further two months to get these Regulations over the line.

But enactment is not quite the same as application, as we noted before. While I picked out a couple of examples last time, it felt sensible to be more systematic about this, given that we are now on the next stage.

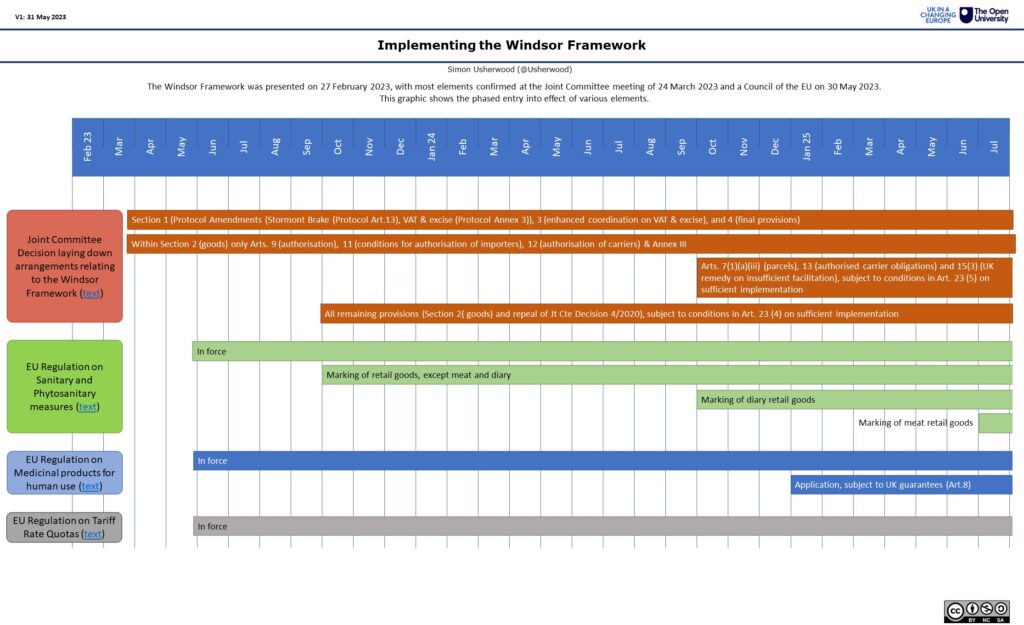

The graphic below sets out the progressive application for the central Joint Committee decision and for the three Regulations: the other elements are effective immediately.

The Joint Committee decision unpacks its provisions, with goods subject to a phased introduction of new measures, conditional upon British implementation. This is similar to the original transitional elements within the Withdrawal Agreement and reflect an intention to allow market operators to adjust over a clear time horizon.

Likewise, the SPS Regulation phases in markings of retail goods, especially on diary and meat where production and distribution chains have been most cross-border pre-withdrawal.

Of course, markings on retail goods is a more general UK headache, with the UKCA mark pushed back to the end of 2024, so producers will need to incorporate this aspect in a more systemic overhaul, which in turn requires a definitive central government position.

Finally, the medicines Regulation will only apply from 2025, again conditional upon several British guarantees.

Recall that all of this comes three years into the notional start of the Protocol. Partly this is the price paid for the breakneck timetable of negotiation and ratification, but it is also a reflection of the British government’s long refusal to accept the Protocol as the baseline for future relations.

Business might be understandably loath to use capital expenditure when policy remains in the air: indeed, even when policy appears relatively clear, misallocation occurs with all its associated opportunity costs.

The take away here is still that implementation will be a long process, rather than an event. Even when we get to the end of this set of transitions, we run directly into the TCA revision in 2025, which might produce further changes. Not to mention the potential effects of a general election.

Relations are thus in semi-permanent flux: the question is how this is managed by the parties and communicated to stakeholders and citizens. Whether that’s easier or harder as we return to the technocratic mode is open to debate, but reflection on that now might seem a prudent course of action.