During the Christmas break, the UK got rid of all its Retained EU Law (REUL). But not really.

The entry into force of the Retained EU Law Act at New Year’s Eve meant that all that “Retained EU Law” got relabelled as “assimilated law”.

As I discussed in my previous post, the Act also resulted in a proscribed list of acts being repealed. This moved things on, but far less than had been the original intent of the Act’s creators.

Now we have a further development, in the first Parliamentary Report on REUL, as mandated by the Act. This fun piece of surveying not only sets out progress, but also – for the first time – planned outcomes.

Before we get to any of this, it’s worth noting the updating of the REUL Dashboard, now in its third year of operation and still throwing up surprises.

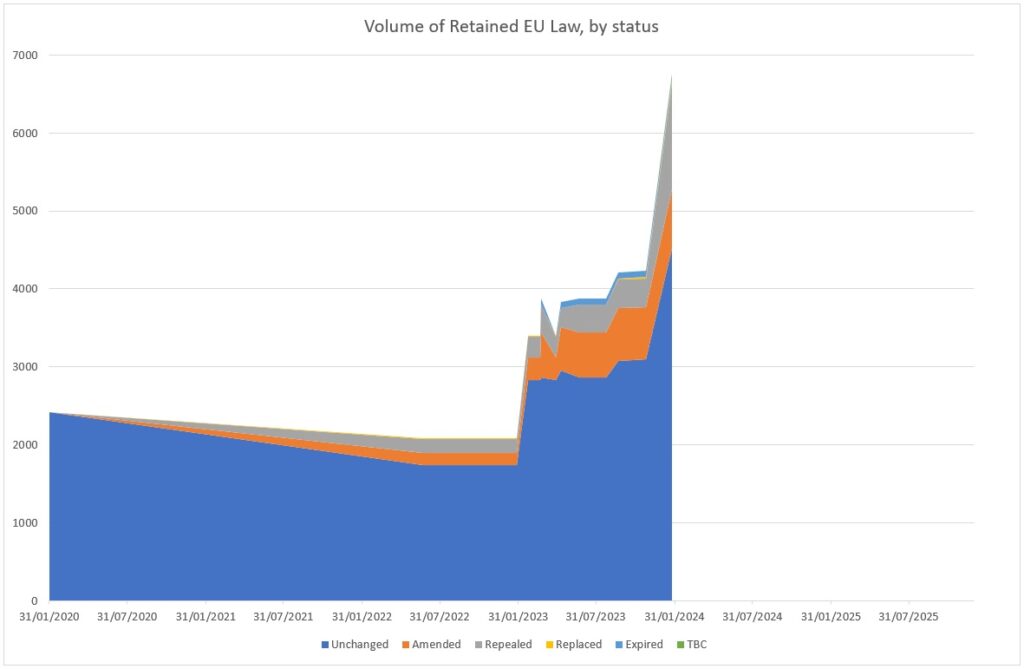

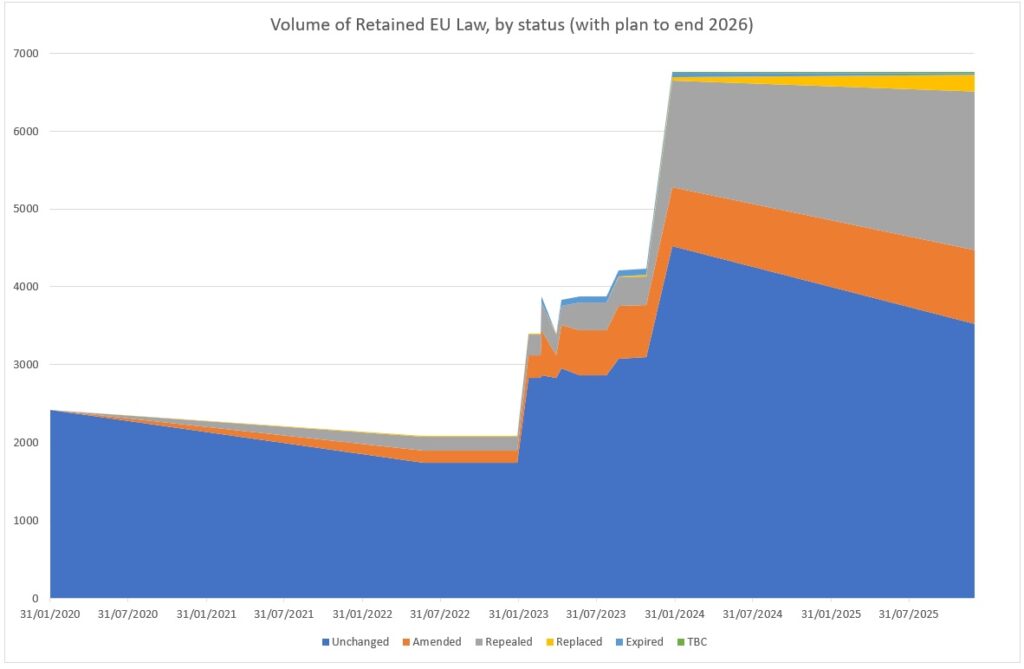

Chief among these is the addition of over 1700 further pieces of REUL, taking the total up to 6757. For reference, the original dataset in June 2022 had 2417 items, or 36% of the current total.

The biggest additions in this latest update come at DESNZ, DEFRA, Treasury and DfT. Given this is the sixth occasion that totals have changed, it would be reasonable to assume it won’t be the last time.

However, the new figures show substantially more repeals than I’d anticipated last month (1369 actuals against 906), as well as more amendments (759 actuals against 647) and replacements (39 against 16). Only expirations was lower (62 against 75), which again makes little sense, given the Act shouldn’t have affected this: data errors are the probable cause here.

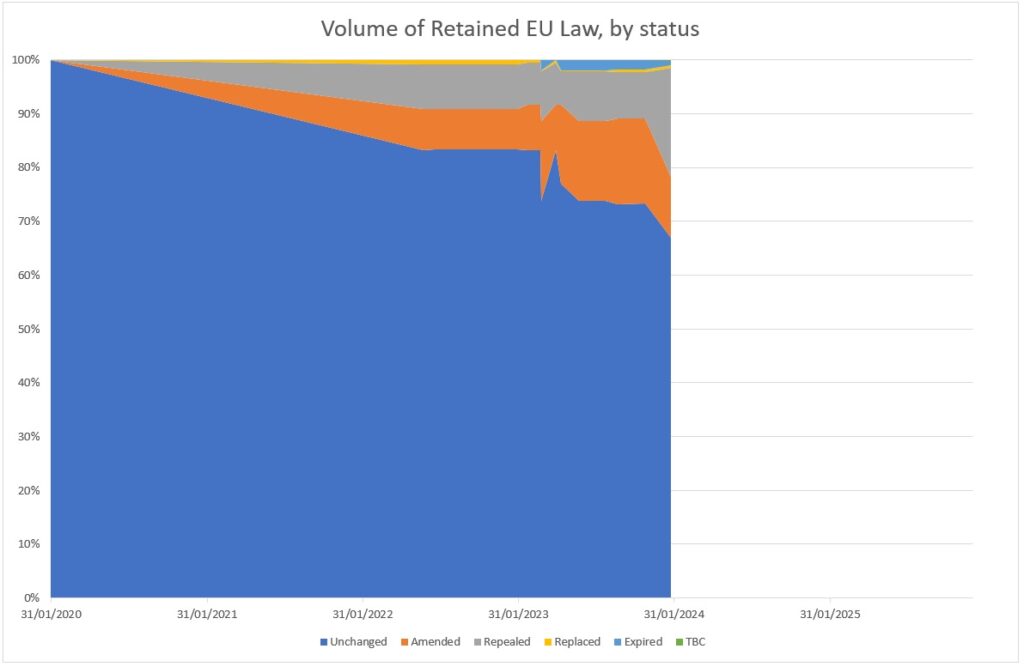

This means 67% of REUL is unchanged, with another 20% being repealed. As you can see in the two charts below, the Act’s passage is noticeable in the overall pattern of change, especially given the massive movement on overall volume.

We therefore have the somewhat ironic situation that while there has never been more change to REUL/assimilated law, we also have never had more identification of items of REUL/assimilated law, nor more listing of unchanged items (well over 4000).

This is precisely why there had been so much opposition to the Act during its creation: no one could be confident about what this mysterious category actually included, so to automatically sunset ‘everything’ would have undoubtedly produced massive unintended (and likely also not-immediately-noticed) consequences.

This point is a necessary function of the Report too.

Government has now stepped well back politically from trying to get rid of all REUL. One might argue this is just a reflection of technical realities, since it was always very likely that some part of REUL would remain obviously useful, but it is still only now that a more formal (if quietly spoken) statement has spelt that out.

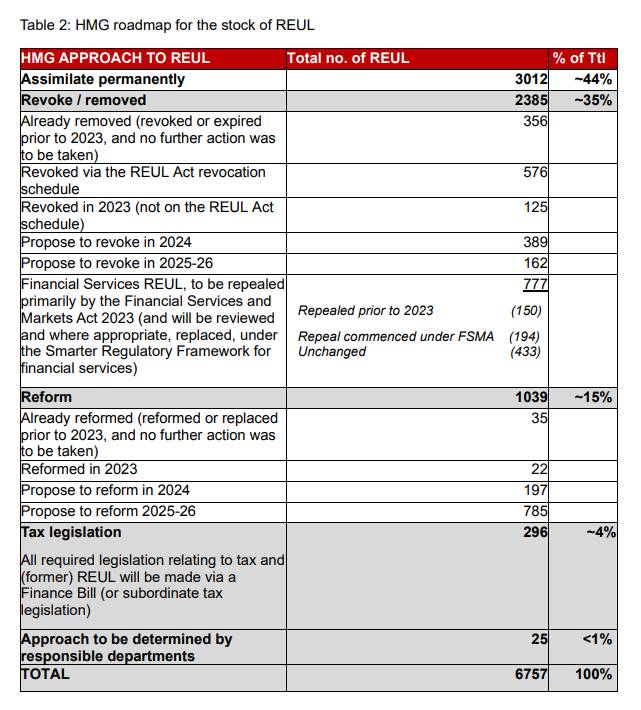

The table below comes from the Report, setting out the end-point vision, wherein about 3000 items will be kept unchanged, another 1000 will be reformed, and over 2000 items revoked or removed.

The table is important for several reasons.

Firstly, it suggests that – barring a small handful of cases – there has been a more systematic evaluation across the piece of what to do. That has not obviously been the case previously when the nominal political objective was to get rid of everything. The test of whether this stands up will come in six months’ time, when the next report arrives: if we again find changes in volume or outcome, then we might be less confident that the datasheet on the Dashboard site holds up.

Secondly, it simultaneously points to continuing confusion. A glance at the categories used here will show that they don’t match those used in the Dashboard, which itself gained the classic “errrm” category of “TBC” this week. While one can argue ‘reforming’ isn’t so different from ‘amending’, ‘replacing’ seems to sit vaguely between ‘reforming’ and ‘removing’, and quite why tax legislation needs its own line is beyond me.

Trivial as this might sound, it does show there still isn’t a consistent language across Whitehall, which will make it that much harder to pursue any systematic agenda. Again, the next Report will tell us more.

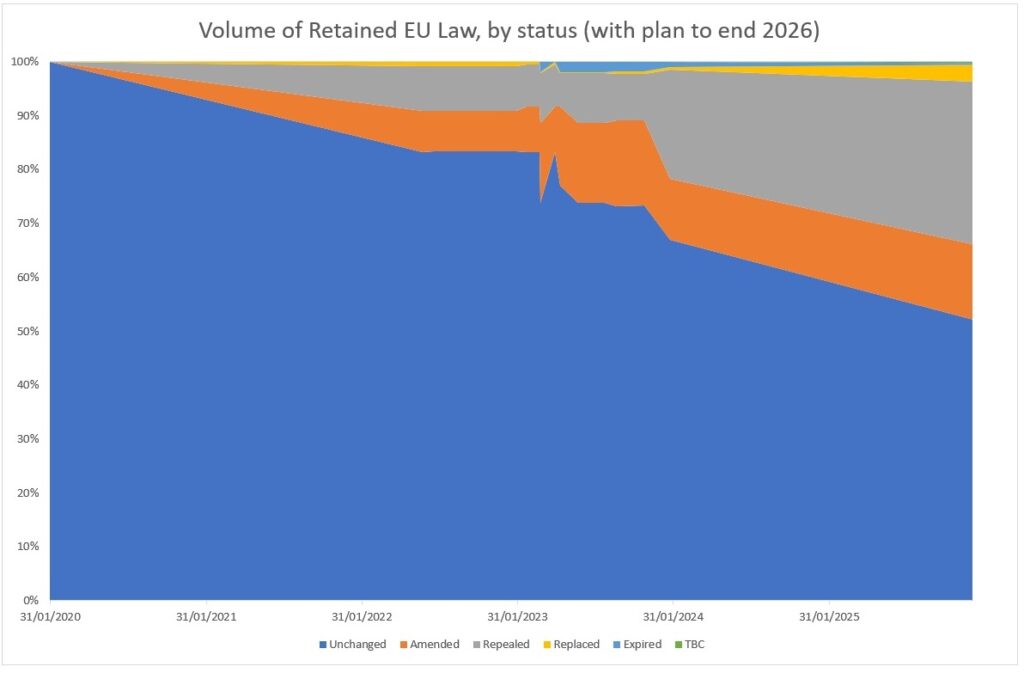

All this said, we can now project out to the end of 2026, using the same charts we used earlier.

Again, we note that we end up with more pieces of unchanged (if assimilated) REUL at the end that we originally thought existed, plus the speed of chipping away at the pile will have been pretty consistent across the entire period, whatever the political messaging.

Of course, this all feeds into the question of progressive divergence from the EU, an issue that will become more relevant over time and especially as and when any new British government wants to rebuild ties with the Union.

But maybe we can leave that dilemma for another day.

Full data is, as ever, available here.