Christmas is, of course, the most Brexit-y time of year.

Who can forget such classic moments as reading treaties under the tinsel in 2019 and 2020, or pondering the no-confidence vote in 2018 over a glass of eggnog?

Obviously keen to keep up the tradition after a couple of fallow years, this time we get to look again at Retained EU Law (REUL), as the sunset clause of the REUL Act comes into effect as Big Ben chimes the New Year.

For those who’ve missed this so far, you can read more here (and here, and here). But the salient points are as follows:

- As a member state of long-standing, the UK used the 1973 EC Act to apply many pieces of EU legislation and other decision-making as part of law within the UK;

- Once the UK left, it was observed that: a) all this EU law shouldn’t apply any more, but that b) it has become very embedded within British legal frameworks;

- The Hard Brexit factions pushed on this (on point a), more precisely), eventually securing the Government’s pursuit of a Retained EU Law Bill that initially declared all the REUL would fall void at the end of this calendar year;

- Much pushback ensued, not least because it turned out no one knew how much REUL there actually was or what it all did, so sunsetting it would cause many more problems than it solved;

- Ultimately the Government conceded the point, moving instead to a schedule in the REUL Act, specifying what would sunset and leaving the rest to continuing efforts to remove or amend it to better fit British interests.

The schedule lists 587 items. Of those, only 553 can be located on the Government’s REUL Dashboard, which is the central repository of REUL listing and work. The rest appear to be almost entirely made up of highly specific notices, but with no indication of why they only appear in the Act. Which rather underlines the point about the lack of a definitive list.

However, this quibble aside, it is now possible to project what the overall effect of the sunset at the end of December will be.

The lion’s share of sunsets come from DEFRA (319), followed by DfT and DESNZ (both 65). Notably, both the Treasury and DBT come in with low single digit sunsets, despite their relatively high volumes of REUL.

DEFRA seems to have had a lot of fisheries agreements and habitat regulations to chuck on the pile, with DESNZ bringing emission trading items and DfT numerous agreements on recognising training of non-EU seafarers.

In short, much of this list is not highly salient or current in content, but rather a clearing out of the legislative roll. Which is fine, but arguably not what Brexit was meant to secure.

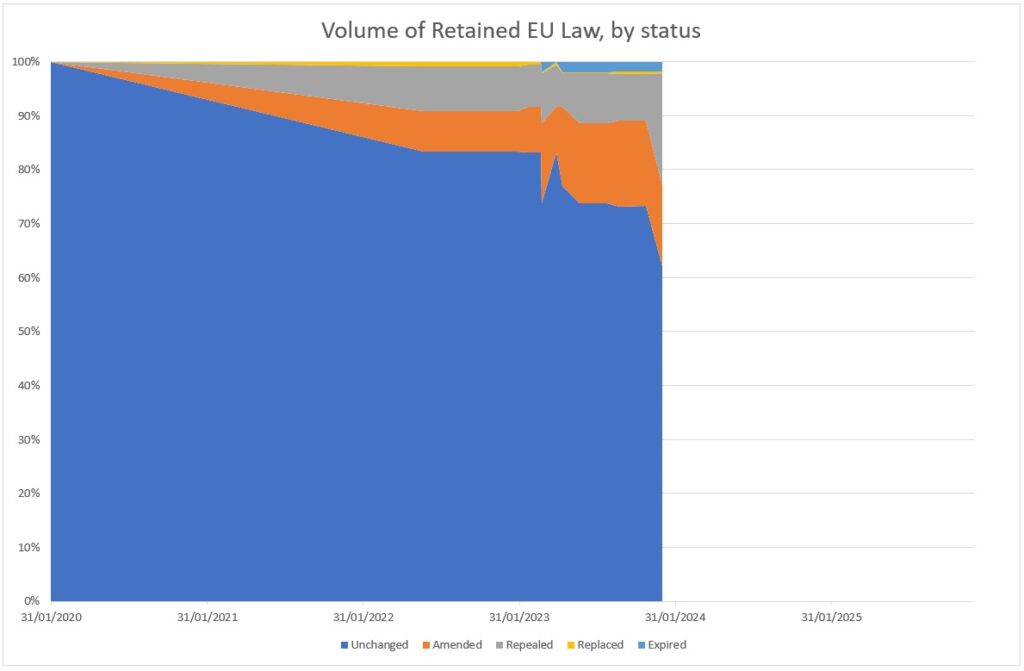

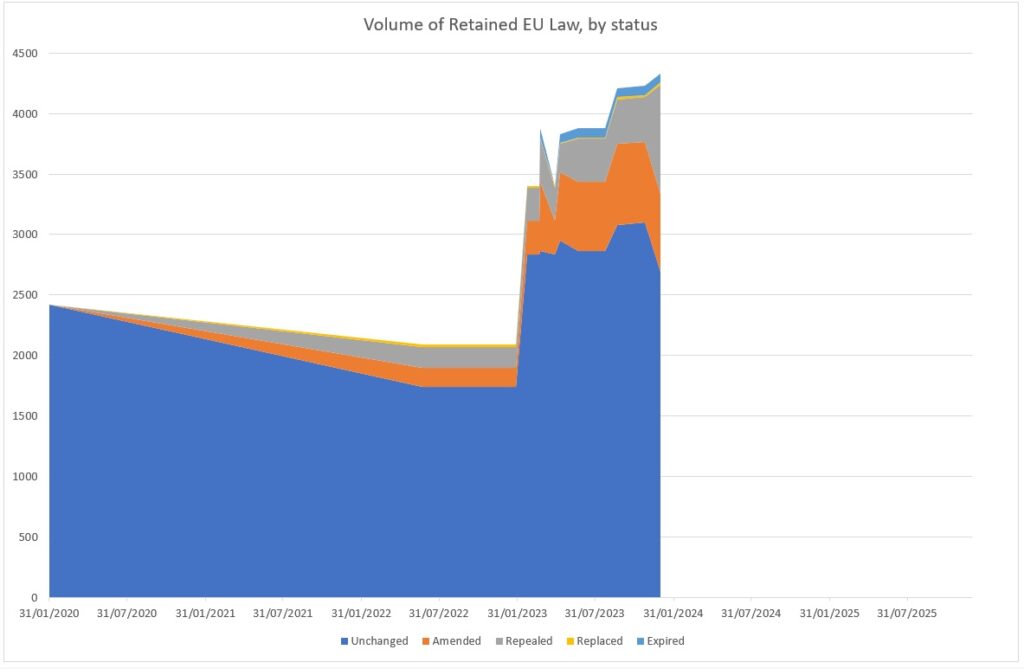

Moreover, despite bringing us close to 1000 pieces of repealed REUL overall, this still leaves over 2,600 items that remain unchanged. As the chart below shows, the progress since withdrawal on 31 January 2020 has been stately rather than rapid, with approximately one-third of identified items undergoing some change.

That picture does however need to be set against that issue already mentioned: the uncertainty about the list. Which has grown from an initial 2417 items in mid-2022 to 5020 today.

The entire exercise continues to raise serious issues.

Firstly, the lack of records that are either exhaustive or consistent makes the switch to a defined list in the REUL Act schedule seem ever more prudent: the uncertainty about what REUL actually exists remains substantial, in turn making any system of blanket sunsetting run the risk of producing numerous unintended consequences.

Secondly, the uneven distribution across Departments of items in that schedule also suggests that any attempt to treat REUL as a homogenous lump is deeply unhelpful. Clearly, there are areas were repeal or sunset is quick and simple, while in other fields the items remain deeply consequential and/or entangled in wider regulatory frameworks. To work to an agenda of simply saying REUL is all ‘bad’ (or ‘good’ for that matter) isn’t very helpful.

Thirdly, we might note that Parliament has been largely excluded from this process: this is very much an Executive-led and -controlled initiative. Which comes back to questions of quite who it is that is taking back control in Brexit.

Finally, while the focus has been on the reform of REUL, it’s ever more important to remember that there is still a material interest in some form of regulatory alignment with the EU. Partly that’s down to Level Playing Field requirements in the TCA, but mostly it’s a function of proximity and the convergence that came from being a long-standing member state: if the UK values trading with its nearest large market then avoiding needless imposition of additional effective barriers to trade needs to be part of the calculations being made.

We’ll return to REUL during the coming years, but in the meantime you can find my datasheets here, including some more charts and the current raw dataset from the Dashboard site.