Today sees a meeting between British and French ministers to discuss the vexed question of fishing licences for Jersey waters. This event is important for a number of reasons.

Firstly, it’s the pathway that got opened up earlier in the week by the French decision not to move to unilateral sanctions over the issue, so that’s a positive development for talking through problems rather than laying down more harsh rhetoric (as both countries have been doing of late).

Secondly, it’s a reflection of the outsized importance that this issue has acquired over the past weeks, compared to its economic (or even its symbolic) value. This is a reflection of the wider low-trust environment that the UK operates in with both France and the EU.

But finally, it’s also the first time that the UK will have secured a bilateral meeting with an EU member state to discuss provisions of the Trade & Cooperation Agreement (TCA). The rigour of keeping to the Commission as the interlocutor on such matters has been exceptional and even the very particular nature of the matter might give others some pause for thought, not least Ireland.

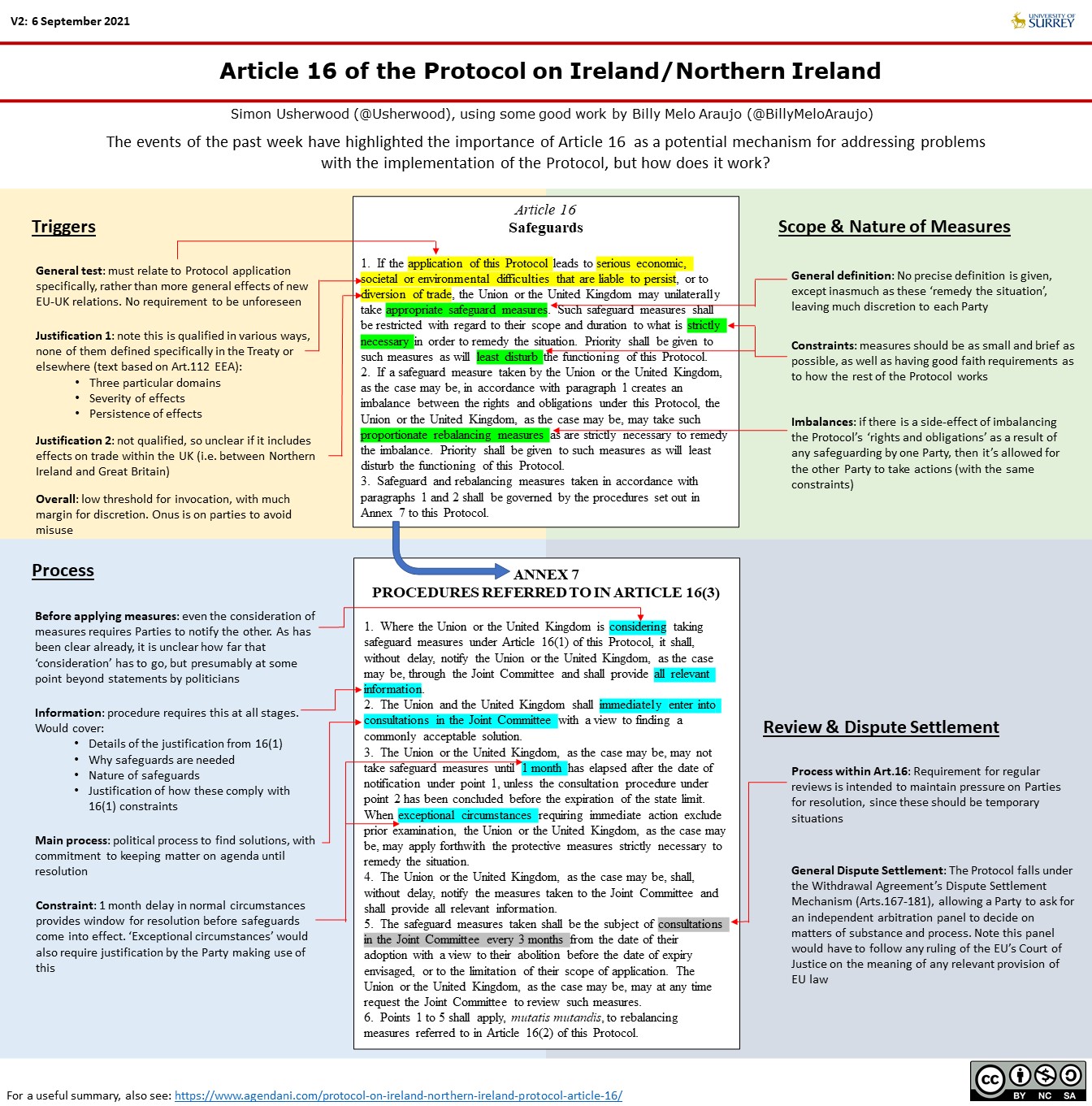

In this context, Jersey might turn out to be an important demonstrator of things to come, even if the practicalities involved are somewhat mundane. Given that this is all a sideshow to the looming return of Article 16 – which is a very much bigger problem – we might loose sight of this rather quickly, especially if a deal can be worked out.

However the entire episode has also underlined a number of issues with the TCA that are likely to be repeated down the line.

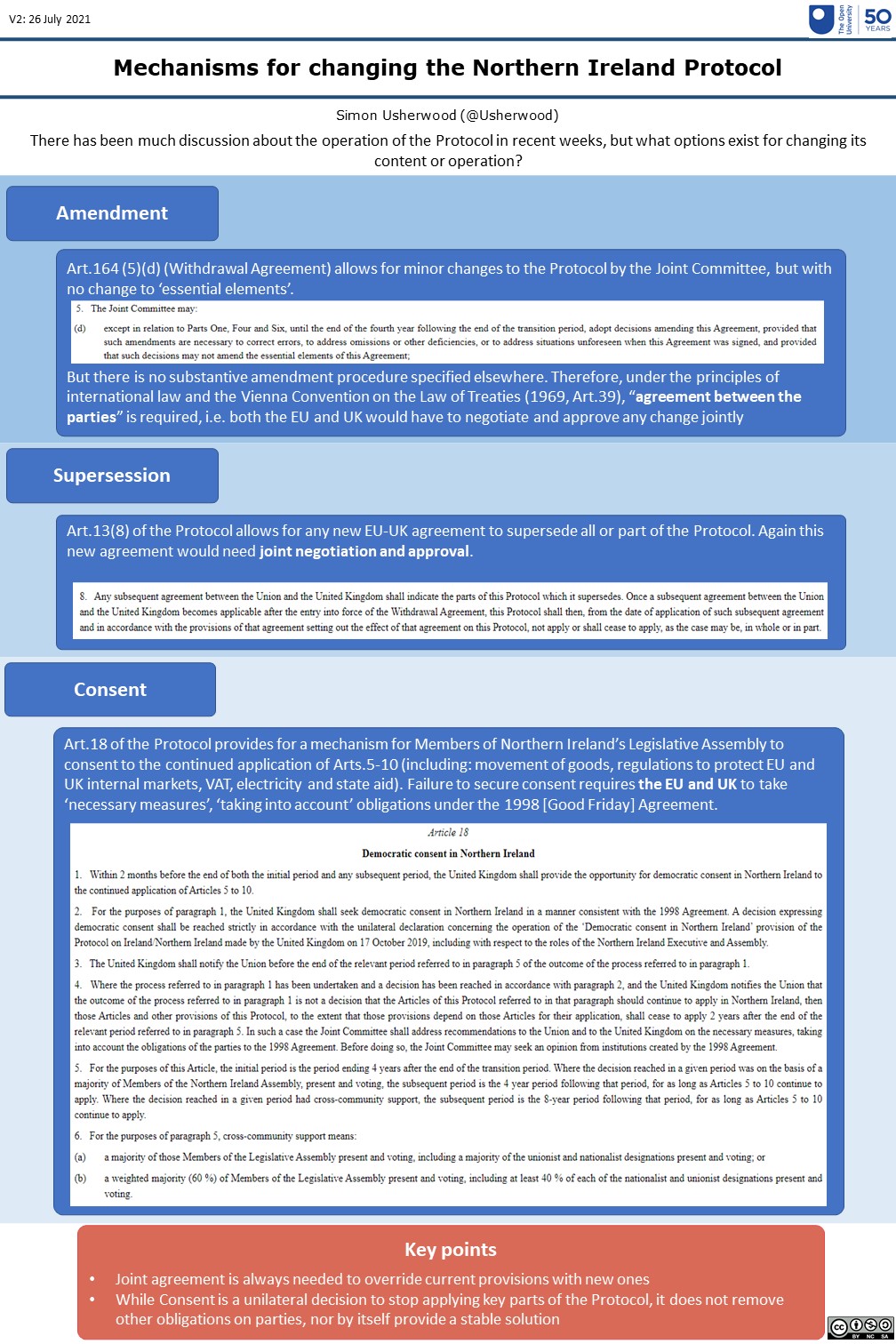

Most obviously, the situation seems to have stemmed from different interpretations of Art.502(1), which requires that historical access to Jersey waters ‘can be demonstrated’. The necessary level of proof is not specified and this appears not to be a practice that can draw on any significant international law: littoral states that break-up and that divide their waters between successors tend not to offer on-going access at all.

The UK government took a rather firm line on all this, asking for GSM traces and the like, something that smaller French boats couldn’t provide because they don’t carry that kind of equipment. As have been pointed out elsewhere, this was a technical issue that was allowed to escape into chancelleries, with all the additional costs that’s incurred.

The vagueness of the provision is only underlined by Art.502(4) which allows for the entire arrangement to be changed without a full ratification process, suggesting this was at best a stop-gap. Perhaps this also explains the noticeably more constrained and proportional range of remedial measures that can be applied in the event of alleged non-compliance (Art. 506(2)) which means that even if the French had been able to convince the Commission to start on this – already a very big uncertainty – then remedies wouldn’t have stacked up to much.

Again, given the more general reading of the TCA – with its multiple dispute settlement mechanisms, regular reviews and termination clauses – this argues that this set of provisions wasn’t fully nailed down, so minimising contagion made more sense.

We can rehearse the reasons for the hurried nature of the TCA’s negotiation, formulation and ratification and who’s at fault for what, but ultimately none of this changes the situation as the parties find it now.

Indeed, it is this aspect that more forcefully comes back to Northern Ireland and the Protocol.

The UK narrative of late has been one of negotiating the TCA during a period of ‘extreme weakness‘, a bold claim given that ratification only came after the landslide of the December 2019 general election. That aside, the Jersey issue has risked playing into that narrative framing, even if it is within the current text and very much smaller. France does have a presidential election on the way, but it also doesn’t want to be the one to crash the already-beleaguered relationship. Hence the Commission’s refusal to accede to French demands to launch measures under Art.506.

If there is a silver lining, then it was the British protestation that French actions would result in the UK bringing proceedings under the TCA’s dispute settlement mechanism. The rhetoric of the need to stick to the provisions of the treaty raised some hollow laughs elsewhere, after the Internal Market Bill and the suggested use of Art.16 to remove the CJEU from the Protocol, but it does show that there is a logic available to working with what you have.

Unfortunately, it has also underlined very clearly that there is a very long road to travel before relations across the Channel can get back to the level they more usually enjoy.