The Level 3 mathematics education modules at the Open University develop certain ideas (module ideas and frameworks) that can help us notice, structure and reflect on mathematical thinking. I’ll be using some of these to analyse my work on a puzzle from the Maths and Stats (M&S) student newsletter, Open Interval.

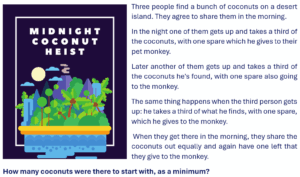

The joy in mathematics is in the doing, so do have a go yourself first!

FIGURE 1: The puzzle

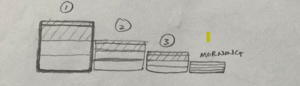

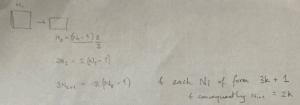

I am particularly interested in the use of diagrams, so rather than jump into using numbers or x’s and y’s, I started with a ‘bar model’.

FIGURE 2: Coconuts as bars. Bounty?

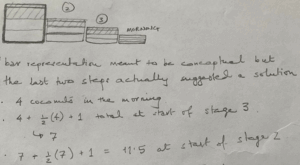

While the bars were intended to be conceptual, the last two stages suggested a numerical solution: that they found 4 coconuts in the morning. I worked backwards from the 4 but it led to there being 11.5 coconuts at stage 2 ☹

FIGURE 3: Problem with fractions!

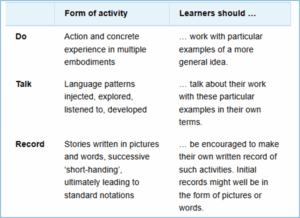

I’ll take a pause from sharing my mathematical work, and introduce one of our frameworks, Do – Talk – Record, covered in ME620 Mathematical Thinking in Schools.

FIGURE 4: DO TALK RECORD summary

While Do – Talk – Record (DTR) is presented sequentially, things aren’t that clear cut! The very act of doing with pencil and paper involves writing (recording) and the talking can be silent talking to myself or thinking aloud. Indeed, some of the writing in my work is my internal talk being made explicit. As doing, talking and recording are inextricably intertwined, the framework is meant to focus on the emphasis or intent at a particular stage, rather than divide activity up into separate boxes of Do, Talk, or Record.

FIGURE 5: Some later stages of recording

Indeed, having worked with it before, the DTR framework now prompts me to take stock when working on a problem, making explicit any emerging ideas.

There is another module idea that has an overlapping cyclical approach, Manipulate – Get a sense of – Articulate (MGA) covered in ME620 and in ME322 Learning and Doing Algebra. I manipulate my various representations of the number of coconuts at each stage, to get a sense of the mathematical relationships involved, which then helps me articulate better representations, which now become available for a further round of MGA.

The 11.5 coconuts (Figure 3) made me realise the puzzle may not be as easy I had initially thought. As fractional coconuts didn’t seem in the spirit of the puzzle, I would need to ensure that the numbers at each stage were positive integers. Such problems have a particular name, Diophantine problems, and can be notoriously difficult. So I decided some algebraic stock-taking may be helpful to ground further numerical work (trial and improvement?).

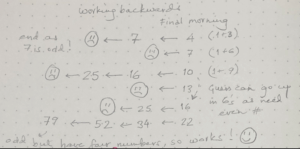

An early formal observation was that at each stage there would be 3k+1 coconuts for some positive integer k. Furthermore, other than the first stage, each subsequent stage would also need to have an even number of coconuts, 2k, the leftover once one share and one coconut (k+1) had been taken from the 3k+1.

Working backwards from a ‘final’ possibility such as 4 or 10 seemed less daunting than proceeding with solving recursive equations of the form N_2 = 2/3 (N_1 – 1) 🤪

FIGURE 6: Working backwards from 4, 7, 10, …

I had my first solution! I was convinced 79 was the smallest possible solution, so I was done. But that seemed quite unsatisfying. What more could I say or do? This leads me to Noticing Structure (in ME322), the final module idea I would like to share here. Join one of our modules to explore others! 😊

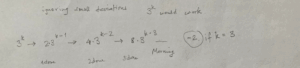

Ignoring the monkey’s singleton share, I need numbers that are continually divisible by 3; why have I not noticed that powers of 3 could be helpful?!

FIGURE 7: What happens with powers of three?

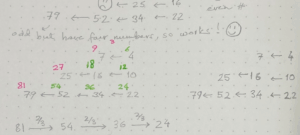

Looking more closely at the one successful sequence I had, and the unsuccessful ones(!), when working backwards, they all ended with a number that was 2 less than a power of three!!! Indeed, if I added in the ‘missing’ 2s, my sequences would start with a power of 3 and then go down to two-thirds at each stage.

FIGURE 8: Pattern spotting or noticing structure?

This structure, of powers of three, and that two-thirds would always then be an even number, aligned with the properties I had observed earlier (Figure 5). The offset of 2 wasn’t quite clear to me, though I knew some offset from 3k was needed to ensure the monkey’s share. This reminded me of the ‘Sharing 17 camels’ problem, and one idea could be to add two poison fruit to the pile of coconuts (which help with the division but remain unclaimed throughout). I had now (noticed) enough structure to use numerical, symbolic and even diagrammatic representations that would yield general solutions.

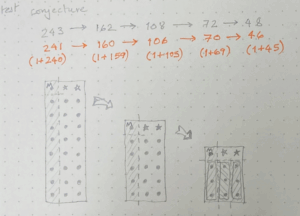

FIGURE 9: Testing numerical and diagrammatic conjectures

How can we be sure that these patterns will always work? I will leave that with you to explore!

As a final takeaway message, the ME322 materials say, “Choosing particular representations can help with noticing structure”. Something for me to bear in mind when trying to crack future puzzles!