This week we chatted to Malcolm Atkins, an Open University Associate Lecturer in Music, who also has a degree in Classics. Malcolm is one of the founders of Avid for Ovid, a group of performers who reinterpret ancient myth through dance and music.

Thank you for talking to us, Malcolm. Where did the idea for Avid for Ovid came from?

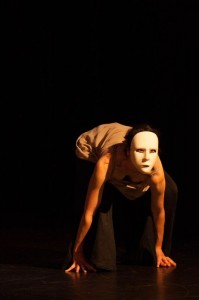

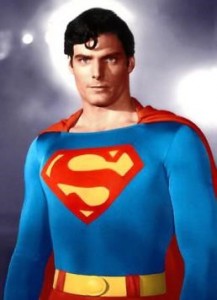

Malcolm and Ségolène performing ‘Lycaon’ at Modern Art Oxford, September 2014. Photo credit Pier Corona

Avid for Ovid (A4O) was formed by three Oxford-based artists (dancers Susie Crow and Ségolène Tarte, and musician Malcolm Atkins) after an involvement in the Oxford University research project Ancient Dance in Modern Dancers, where we had brought our practical knowledge as performers to explore the long forgotten form of tragoedia saltata, or ancient Roman pantomime, solo storytelling through dance and music. We formed A4O as a group of performing artists to explore from our perspective as artists the potential of using principles and ideas from ancient dance and music in contemporary performance. We later invited Birmingham-based dancer Marie-Louise Crawley to join the group. We found the potential of this solo dance form to be enormous – it can really communicate with an audience of any background and can be performed almost anywhere (and in this we seem to be continuing the Roman tradition).

Can you tell us a little more about the performers? Did any of them, other than you, have any prior knowledge of ancient poetry?

Susie Crow is a ballet dancer and choreographer interested in the expressive and narrative potential of ballet, and how skills and approaches from Roman pantomime may have informed its inception; Ségolène Tarte is an academic as well as a ballet dancer and researches as a Digital Humanist in close collaboration with classicists at the University of Oxford; Marie-Louise Crawley is a choreographer and contemporary dance theatre artist who also studied Classics at Oxford.

What might someone who comes to one of your performances expect to see?

We attempt to create narrative through movement and sound. The choice of movement and sound is eclectic and represents the diverse practices and genres we have all worked in. I use a range of instruments (in the spirit of this dance practice which seems to have used all available resources) and create soundscapes as well as direct motivic and thematic interactions, word setting and word painting. The dancers often choreograph a setting of a myth and as with the Roman practice shift from one character to another in unfolding a narrative. They are informed by a range of practices including ballet, mime, kathak [1] and butoh [2] – all of which have a unique relation to narrative. In fact this is also similar to the way musically I use traditions of leitmotif, thematic transformation, rhythmic pattern and power and dissonance as appropriate. Much of this is inevitably informed by our cinematic and visual culture.

What you will see is something exciting and engaging in a way that is far more accessible than much contemporary dance because the focus on narrative allows communication with all – just as the Roman practice did.

What is it about Ovid’s poetry in particular which lends itself to this kind of performative storytelling?

Within the Metamorphoses there is an incredible range of narrative and characterisation and perhaps this is why this was such a favourite of Shakespeare. We have the opportunity to select from so many different styles of story and presentation of character through the music and dance we create. The poetry as a compendium of myths also seems to have an incredibly challenging and subversive meta-narrative. Unlike the overt challenge of the radical exploration of myth in Euripides, Ovid is far more subtle in the way he relentlessly punctures male patriarchal pomposity although more often through flawed divinities than mortals. This ambivalence towards authority and emphasis on its malign side lends to the possibilities of exploration in dance and musical interpretation as does the breezy tone of Ovid as he skips from one scene of abject and unjustified misery to another often juxtaposing farce and tragedy.

Do you personally have any favourite episodes from Ovid? Could you tell us why you are drawn to certain parts of his poetry over others?

One of those awkward lycanthrope moments. Ségolène performing ‘Lycaon’ at Modern Art Oxford, September 2014. Photo credit Pier Corona

I have become particularly attached to passages that we have performed because my engagement with the text has deepened (often as I recite or sing it in Latin). The visceral power of the description of Lycaon’s transformation to a wolf was captured through a recording suggested by Ségolène where the text was recited like ‘maggots in the brain’. When Ségolène performed her interpretation a child had to be led out crying from a performance that had no graphic violence. The pathos of Aurora’s grief at the death of her son – particularly relevant in a time of so much desolation that we see daily on the news – was so well expressed by Susie’s exploration of archetypes of grieving. Marie-Louise’s exploration of Myrrha and the desperation that leads to her transformation to a tree (and the very powerful subtext of the girl as a victim of patriarchal desire that resonates with our time) was particularly unsettling (as was the subject) and to me lent to an expressionist theme and the solipsistic musical misery of fin de siècle Vienna. On top of this the subversive story of Arachne who studiously reports the misdemeanours of our betters against the strident defence of Athene was brought home to me by Ségolène’s inspired interpretation. Ovid’s lack of a decisive judgement is all the more powerful in highlighting the abuse of power – something else that strikes a chord with contemporary politics and conflicting media narratives sponsored by corporate power.

For readers of our blog who are interested in seeing Avid for Ovid perform, could you tell us when and where your next performance is taking place?

We are next performing at the opening of a recreation of Ovid’s Garden in Winterbourne Gardens at the University of Birmingham (58 Edgbaston Park Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham) on the 18th June at 3pm. This is a free performance to celebrate the opening of the garden. More details are available here.

Where can our readers find out more about the project?

They can visit our blog and Facebook page, find us on Twitter (@Avid4Ovid) or contact me via email: [email protected].

[1] Butoh is an expressive dance theatre form which arose in Japan in the late 1950s; often incorporating playful and grotesque imagery, extreme or absurd situations and slowly evolving movement, performed in white body make-up.

[2] Kathak is one of eight Indian classical dance forms; originating in North India, it combines the telling of stories through codified gestural movement with a more formal vocabulary incorporating virtuosic and percussive footwork, rhythmic complexity and spins. (With thanks to Susie Crow for providing definitions.)